The partnership between the SWF and Sofronichrist has resulted in the creation of the SWF YouTube channel, which will feature a variety of formats, from interviews to podcasts, all revolving around Furtwangler’s art.

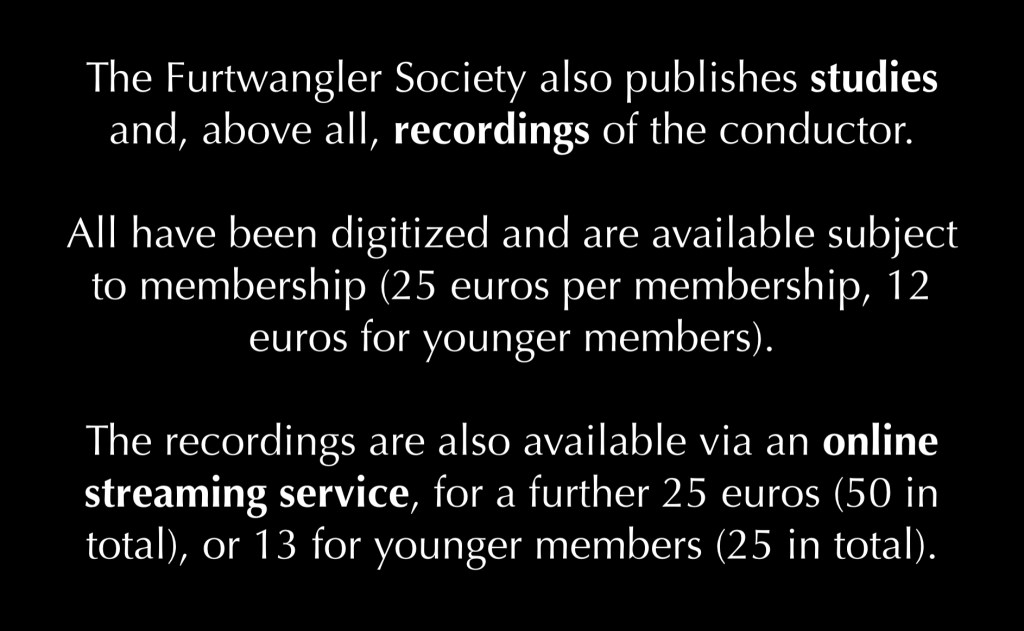

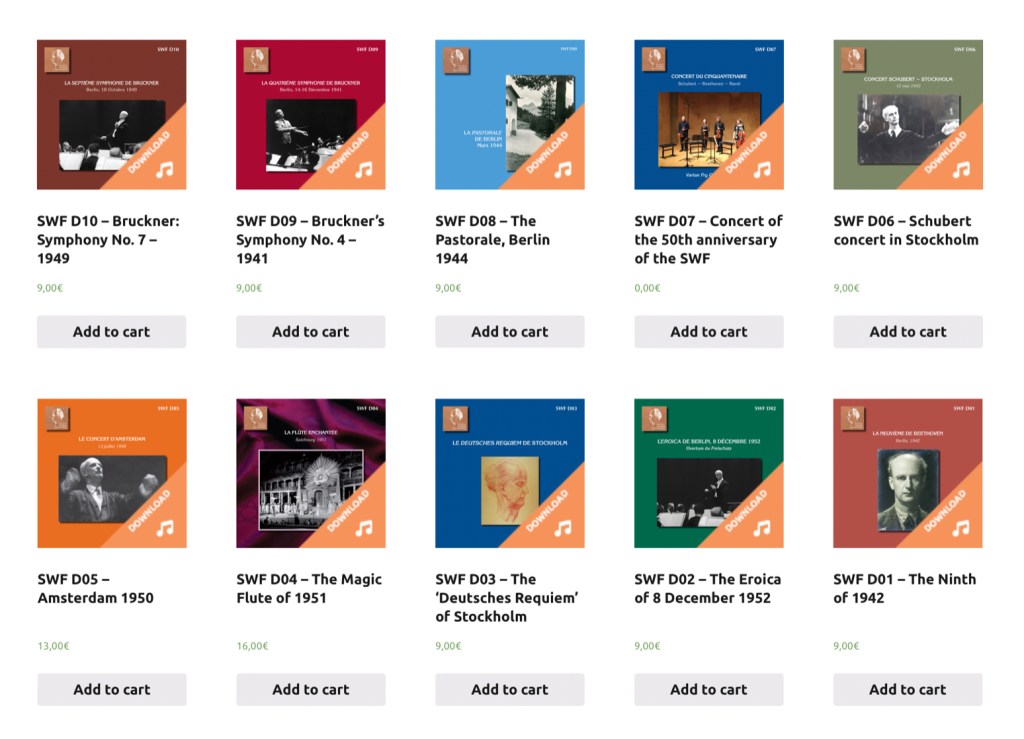

THE SWF WEBSITE : furtwangler.fr

What links each of Wilhelm Furtwangler’s interpretations is undoubtedly above all a vision. A vision that is unusual, original and even extraordinary among all the conductors who have marked the 20th century, and in particular among the Romantic conductors from whom he stands out. In this respect, Furtwangler remains a man of the 19th century, who was lost and sometimes drowned in the turmoil of the 20th century, who lived through two world wars and remained an idealist in spite of everything, at a time when a real form of disenchantment was taking place in intellectual circles.

Wilhelm Furtwangler is a conductor with a resolutely romantic style, heir to the conducting of Richard Wagner for example. His music is truly alive in the quasi-organic sense of the term – he considered it in its uniqueness, as a totality – in the physical, sensitive, but also metaphysical sense – and we shall see that his art appears more in a form of transcendence than immanence. Although the composers and works interpreted by Wilhelm Furtwangler vary enormously, his repertoire was very extensive, there are constants that do not change, there is a common vision present at the heart and even at the foundation of each of his interpretations. Indeed, Furtwangler was a whole artist, who did not adapt so much to the work, in the sense that he was not an artist so inclined to make concessions. He had his own general conception of music, and in this respect it is worth noting that he did not hesitate to change the orchestration of works to make intelligible what he wanted to hear. Furtwangler’s art thus communicates an extremely lyrical, very pictorial and sometimes even sensual vision, which transcends each work he plays, and is thus embodied in a primacy given to energy in both the themes and the transitions.

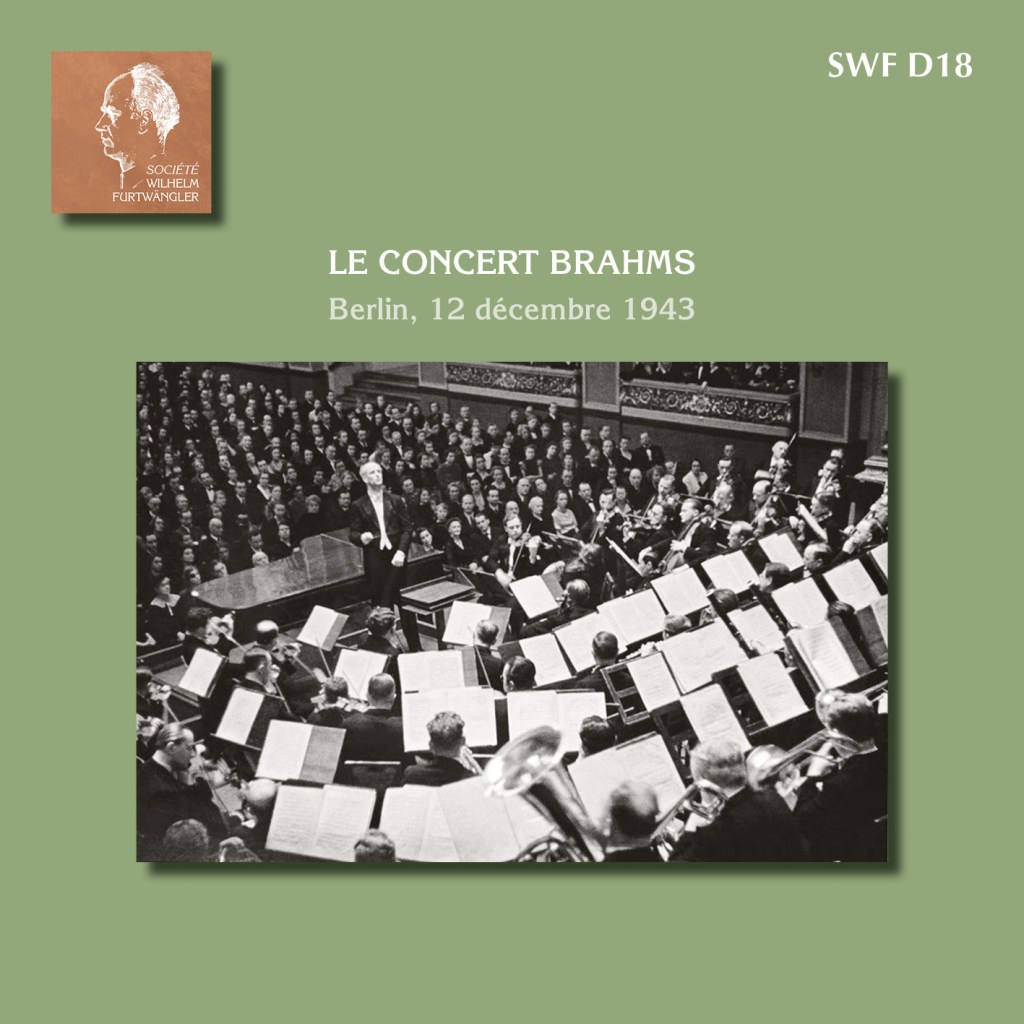

In Furtwangler’s case, the contrasts are finally smoothed out quite regularly, for example, the dark moments and the moments of bravura found in Beethoven – if they can be called that – are contained with Furt in a coherent whole, they can be distinguished separately but they are part of a whole. The two coexist – which implies that they exist. What first comes to mind when listening to Furtwangler’s « Eroica » is this complexity, this alternation of atmospheres yet so different, which makes one of the most important points of his direction intelligible: the themes are as worked out as the transitions. This coherence in difference is what allows Furtwangler’s Beethoven to be truly human – which is far from always the case in the Romantic tradition – while retaining its metaphysical properties. And where Furtwangler’s Beethoven was properly human, what is perhaps more striking about his Brahms is the force that emerges, more powerful – but perhaps less so – than in Beethoven. Brahms’s music is certainly organic, but above all it becomes airy, and this is heard more in Furt’s Brahms than in his Beethoven – perhaps also because one imagines Beethoven more airy than Brahms. However, it should be noted that Brahms music is more often than not chiselled: in Toscanini, Mravinsky or Carlos Kleiber, for example, the emphasis is on relief and in Kleiber even on rebound. Furtwangler, on the other hand, binds with lyricism, it is in an almost pictorial expressiveness that the phrase takes on relief, the music breathes without becoming sculptural, and it is each of these elements put together – the music must above all be rendered in its uniqueness with Furtwangler – that allows this expressive brushstroke to go towards the unknown, to take the listener beyond what could be expected, towards dimensions that no one else would allow to be contemplated.

Furtwangler’s music is transcendent in the sense that it brings together each of its constituent elements to make itself at times almost purely metaphysical – and at other times a little less so, but always remaining in essence metaphysical. There is a kind of additional, ineffable dimension that rises up, while already coming from above, to encompass and allow us to contemplate the whole, while never becoming detached – in the sense that both the conductor and the listener remain engaged. This is also what allowed Furtwangler’s conducting to never fall into any form of mannerism, as all the other representatives of the Romantic tradition have done at one time or another – if one can speak of tradition, let us mean Abendroth, Mengelberg or Kabasta.

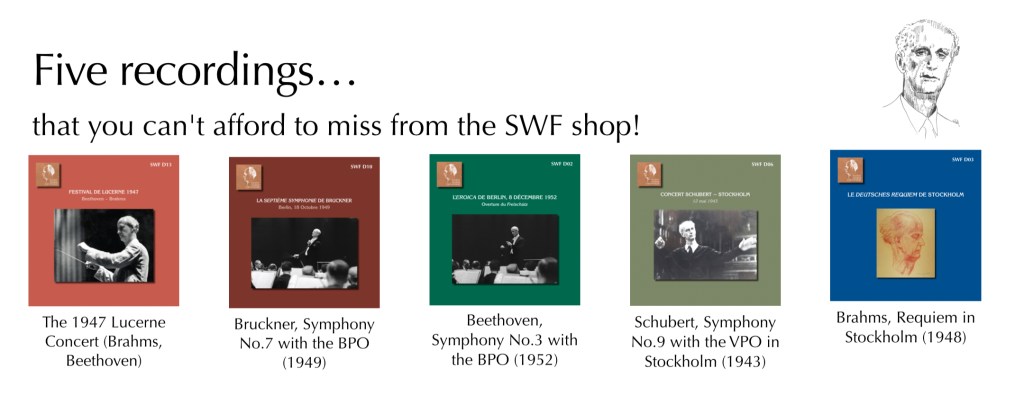

Furtwangler’s discography, with the exception of baroque music, is quite homogeneous – in the sense that absolutely everything deserves to be heard. Furtwangler in the studio was as extraordinary as he was in public, except that he was far more unpredictable in concert. Many of his studio recordings, especially those from the post-war period, are available in very high audio quality – especially the latest restorations from Studio Arts et Son in Annecy. Schubert’s ‘Unfinished’ and ‘Great’ remain high points, Beethoven’s symphonies – especially the ‘Eroica’, recorded in 1952 in a superb recording, and the 1950 Seventh, now in great sound quality – and Schumann’s – that legendary Fourth, where the themes and transitions are the most powerful ever recorded – Mozart’s Symphony in G minor, K.550, recorded with the Vienna Philharmonic in 1948, which is a prime example of the best that Romantic interpretation could muster, and of course the three operas Tristan, Fidelio and La Valkyrie. The public recordings are of course equally interesting, not to say better in all honesty, starting with Brahms – the first symphony in Hamburg in 1951 or Berlin in 1952, the second in 1945, the third in 1949 and the fourth in 1943 or 1948 -, Beethoven – Fidelio in 1950, Furtwangler’s favourite opera, the « Eroica » of 1944 in Vienna and of 8 December 1952 in Berlin, the fourth in 1943 the fifth in 1943, 1947 or 1954, the « Pastorals » of 1944, 1947 or 1954, the seventh in 1943 in an interpretation of unprecedented violence, and of course all the ninths, especially in 1942, in 1951 at Bayreuth and the Vienna versions -, Wagner – the Tetralogy at La Scala or the Covent Garden excerpts in 1938 -, Weber – the Freischutz in stereo in 1954 -, Mozart – Don Giovanni, the Flute of 1949 -, and so much more!