The original podcast (narration in French, English and German subtitles)

After trying to show what made Furtwangler’s Brahms so special, I’d like to talk to you about the conductor’s vision of Beethoven’s symphonies, and why this vision, even if it’s a purely personal opinion, is as brilliant as it is problematic. Not in the sense that it should be banned, of course, we’re talking about Furtwangler, but quite simply because it raises problems, because it raises questions.

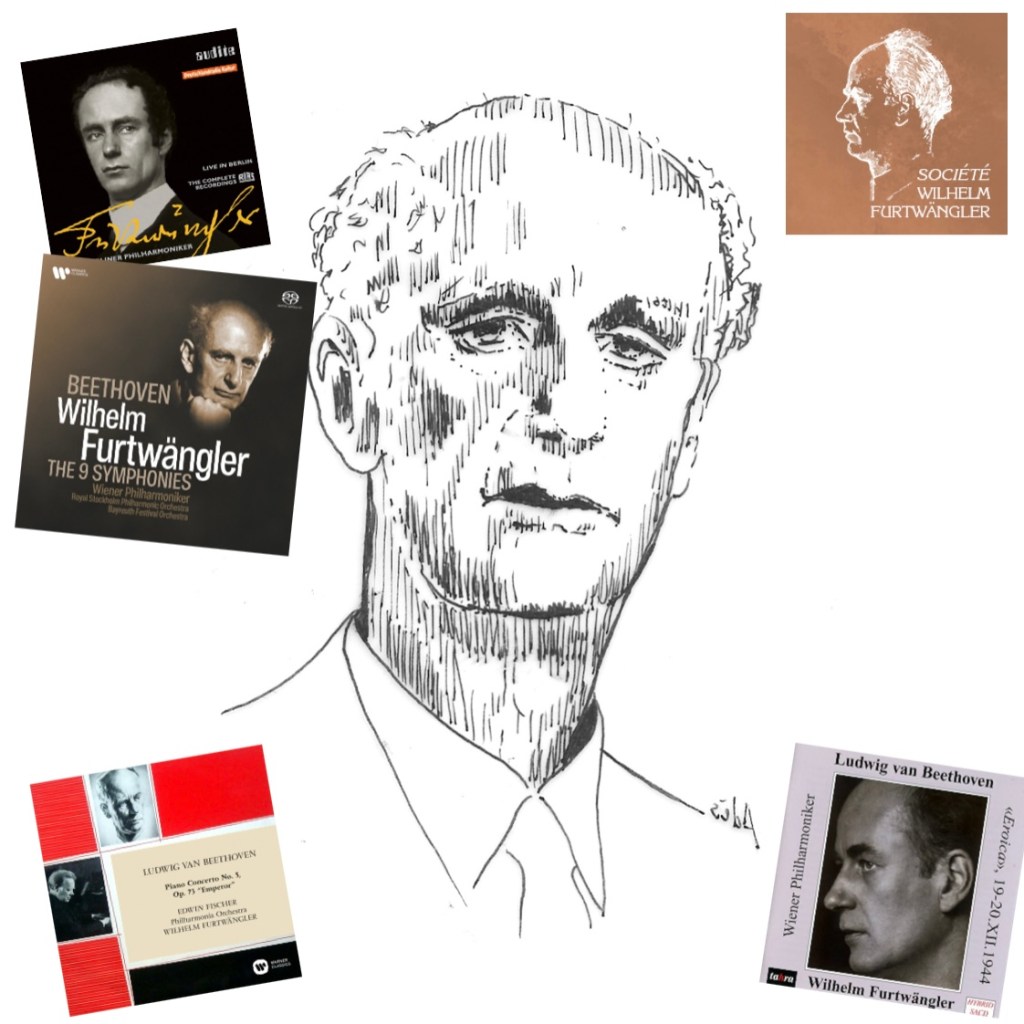

What perhaps immediately springs to mind when we talk about Beethoven is all the humanity that runs through his work, and in this respect, Furtwangler’s Beethoven is resolutely human, but he is also, beyond humanity itself, truly idealistic in my opinion. But above all I would like to ask the question: what is it that unites Furtwangler’s vision of Beethoven? For the purposes of this study, then, I propose to focus solely on the symphonies, although we can also discuss the overtures, the concertos – although we’ll talk a bit more about them later – and, of course, Fidelio. But let us begin with a brief overview of Furtwangler conducting Beethoven’s symphonies, as I did with Brahms – the article and video have already been published.

So, speaking of the First Symphony, I’d like to start with a word from Sami Habra, who was for a long time the voice of the Furtwangler Society, and who, speaking of this early symphony, said that he wanted to hear it not as the candid work of the young Beethoven, but with the vision that Beethoven would have had of it ‘having written the other eight’. And what is, regardless of what one may think of Sami Habra’s opinion, in my opinion truly indisputable, is that at least part of the interest of the first symphony lies in the fact that it already contains in germ all the qualities that will carry the eight that follow. It’s all there already, and will only become apparent in retrospect, once you’ve gone through the whole of Beethoven’s symphonic corpus. Furtwangler is completely in line with this retrospective reading, and he thus endows the First Symphony with a certain metaphysical dimension, and in any case, from the point of view of his apprehension of it, I think we can put forward the hypothesis that he considers it as he would any other of the nine. There are several recordings of the premiere by Furtwangler, but the most interesting is, I think, rather than the very late 1954 concert in Stuttgart, the studio recording with the Vienna Philharmonic – on HMV, now available from Warner. In fact, I think that Furtwangler is extremely interesting in the studio, as long as you give him the technical means, in terms of recording technique, to express himself properly. In other words, if he is allowed to unfold the organic dimension of the music over time, which is much longer than with other conductors. This recording of the First Symphony is already an excellent first synthesis of what Furtwangler does best in Beethoven: tension, multiple dimensions, dizzying depth of approach. It’s a real milestone in the discography of the First Symphony, in stark contrast to Toscanini’s version – because I think that’s far from always being the case, it’s perhaps even more of a personal opposition than a purely musical one, with Brüggen, who in 2011 seems to have learnt a lot from Furtwangler, but we’ll talk later about Frans Brüggen’s relationship with Furtwangler’s music.

On the other hand, I am personally much less won over by Furtwangler’s vision of the Second Symphony. Let me qualify this, however, by adding that the only version we have is this 1948 recording, with the Vienna Philharmonic but recorded in London, of a complete cycle of which this is the only trace that has come down to us – and what a pity, really. So perhaps it’s the really bad sound recording that’s ruining my appreciation, despite, let’s stress here, the excellent work of Christophe Hénault of Studio Art et Son in restoring it in the new box set released by Warner, offering the complete symphonies by Furtwangler on hybrid SACD. That said, there is no denying the great qualities of this performance, such as its sense of architecture and construction, which lends complexity to a work that often seems pale in comparison with the rest of Beethoven’s symphonic output. What is clear is that a contemporary vision such as that of Giovanni Antonini, whom I adore in this symphony, or even visions from the golden age of recording such as Hermann Scherchen or René Leibowitz give a much better account, in my opinion, of the essentially lively and sensitive character of the work, in other words of the symphony’s ultimately rather non-metaphysical dimension, whose essence is to be found rather in the suppleness of the melodic line, and one might almost say the ‘swing’ and lightness.

Let’s move on to the monument! As far as the ‘Eroica’ is concerned, there’s no shortage of discography! The first is from 1944, in Vienna, with Tahra. Then, still in Vienna, but this time in the studio, in 1947, also on Tahra, or in the Warner boxed set featuring all of Furtwangler’s studio recordings – that famous 55CD set, released in 2021. Then there’s 1950 in Berlin, on Audite, then 1952 in Vienna, the famous studio recording released at the time by HMV, not forgetting a second from 1952, in December, this time in Berlin, available on Audite, or in the magnificent SWF report – which is available as a download. Let’s start by stating the obvious: all these versions are not only interesting, but absolutely magnificent. However, there are significant differences between them. The first that springs to mind, if we’re honest, is the tempo. In 1950, for example, Furtwangler was faster, but also lighter than in 1952, with the same Berlin Philharmonic. In 1947 in Vienna, he was also livelier than in 1952, in a studio that proved to be absolutely sovereign in its flexibility. But you’ll notice straight away that I’ve left one out, and in fact I did it quite deliberately! Because this is a summit not only in Furtwangler’s discography, not only in the discography of the ‘Eroica’, but quite simply in the history of recording! In 1944 in Vienna, then, in a live recording captured in a superb recording by Friedrich Schnapp, we find all of Furtwangler’s qualities: ineffable expressiveness, tension that becomes trying for the listener, metaphysical depth, lyricism, contrasts, and above all total commitment to a work whose monumentality is fully restored in the performance. Here’s another quote from Sami Habra on Furtwangler’s ‘Eroica’: ‘When the theme began, there was a certain majesty that I hadn’t heard anywhere else. The first forte flowed logically by progression from the first piano and, as the movement unfolded, all the jigsaw pieces fell into place. I had never imagined such a construction possible, never heard such beautiful fortissimos. I say beautiful, not loud. Now I know why they are beautiful. It’s because they have tension. […] The beauty of Furtwängler’s fortissimo in the musical discourse, the continuity of the melodic line that runs from one end of the orchestra to the other, that stays in one desk, passes through the others and returns to the source, is admirable. You never lose it. In his musical discourse, there is a certain quality of grandeur, not just physical but metaphysical. With Klemperer, there’s that same physical grandeur, like the menhirs of Carnac. But with Furtwängler, the stone is alive…’.

After the Third comes, logically, the Fourth, the first of Beethoven’s great symphonies known as ‘even’. There’s a fairly widespread idea that the odd and even symphonies call for different qualities in the performer – which isn’t completely unfounded, by the way, it’s quite intuitive when you listen to them – and that the qualities of some conductors are better suited to the odd symphonies – like, typically, Karajan – and others to the even symphonies. But it should be noted that we are beginning to run out of examples of the even-numbered symphonies, perhaps because the category, the unifying element in the statement ‘Beethoven’s even-numbered symphonies’, is in fact difficult to identify – it is possible to think of a conductor like Hermann Scherchen, but here again it is complex to find unity in these symphonies. Indeed, while there is perhaps a more visible rhythmic flexibility in the even-numbered symphonies – and this is perhaps why one might intuitively think of Scherchen – what is it that unites symphonies like the Second or the Eighth, which are light, lively and marked by the influence of or homage to a composer like Haydn, and others that use flexibility to be more illustrative, like the Sixth, or simply build on contrast, like the Fourth? In fact, the important thing to remember is that each symphony must be conceived as a separate entity. But Furtwangler is rather systematic in his approach. He applies the same general conceptions to the entire Beethovenian symphonic corpus, which explains a reservation I had already expressed about Furtwangler’s Beethoven in the previous article – and video – about Furtwangler’s Brahms. In fact, Furtwangler applies a post-romantic conception, marked by metaphysical questioning embodied in the breadth of expressivity, to a body of work that is entirely polymorphous. Furtwangler’s Fourth by Beethoven is thus what might be called a hybrid object, which seems to evacuate narrative contrasts in order to provoke vertigo. But is this the spirit of the work? When you listen to Carlos Kleiber, Hermann Scherchen or, more recently, Jos Van Immerseel, on period instruments, you are dealing with a work that is above all luminous, marked by a lively gaze, not without questions – as in the introduction to the first movement – or even reservations or nostalgic flashbacks – the second movement – but there is no question of metaphysical vertigo. Having said that, this hybrid object that is Furtwangler’s 1943 version – which to my ears is more interesting than the 1952 recording, which is itself surpassed by a rather underrated 1950 recording, although in both cases the approach remains slightly fixed – obviously deserves to be listened to, as it is a kind of UFO completely apart in the discography, and reveals unknown aspects and facets of the work, which remains fundamental.

But after these ramblings on the Fourth – I have indeed digressed a little! -Let’s talk about the Fifth Symphony, about ‘destiny’. This is the work that Furtwangler conducted the most in his entire career. Here again, he gives a very singular vision. Firstly, through unheard-of variations in tempo, which would be considered bad taste in any other performer – which no doubt gives an idea of the vertigo that Furtwangler’s greatness can provoke. The spirit of each movement is brought to a climax, to the brink of the abyss. The first is ponderously slow and dark, matched only by the lyricism that acts as a source of light within it; the second is sovereignly elegant, the third insanely intense, and the last a race to the abyss whose tempo, which I suppose is the fastest in the entire discography, contrasts in perfect symmetry with the first movement. As this is the work that Furtwangler performed most in his lifetime, we obviously have a plethoric discography, as with the ‘Eroica’. We can start with 1926, the very first studio recording of Furtwangler’s career. Unfortunately, this is a recording of mediocre sound quality, which I’m afraid gives us no real insight into Furtwangler’s art. We then have a first vision, lively and allant, more natural than the one that followed, one might say, closer to natural flow than to the forces of fate, which we find in two fabulous versions. One is the 1937 studio version, magnificently restored by Studio Art et Son in the Warner box set, and the unjustly little-known 1939 concert, released by the Berlin Philharmonic label. These two testimonies to Furtwangler’s first vision were conducted by Furtwangler with ‘his’ Berlin Philharmonic. The war, as we know, marked an intensification and a break in Furtwangler’s style. In 1943, Furtwangler offered a vision of extreme violence and hopelessness, almost ending in descent rather than elevation. The various variations and changes have probably never been so strong in an interpretation of the Fifth. After the war, all versions of Furtwangler would be marked by the darkness and despair that had appeared in 1943, whether in 1947, for his return to the stage, or even in 1954. This last year gave rise to two versions of extraordinary formal beauty, first in Berlin, in public, and secondly in Vienna, in the studio, in a mastery to which the recording gives us access – at least in part – as well as to Furtwangler’s famous ‘sound’. In the recordings of Furtwangler that have come down to us, we don’t always have experience of this crackling sound, and this 1954 studio, with its extraordinary sound recording, gives us privileged access to it.

In the wake of the stormy Fifth, Beethoven published his ode to nature: the ‘Pastoral’ symphony. This is an illustrative symphony, which takes on the task of describing certain sensitive experiences of nature, or of what takes place in a natural setting – the peasant dance, for example. But surprisingly – or less so when you know him – Furtwangler will resolutely pull the work towards abstraction, towards what is purely beyond what is described, bringing back a physical dimension through the organic dimension of his direction. The lyricism is absolutely total, and is the precondition for the possibility of two extremely slow first movements, which are nonetheless firmly rooted in the discourse, and which do not in any way lapse into evanescence – in which case the tension would be lost. From the third movement onwards, the tempo becomes more urgent, preparing the paroxysm of tension that will come in… the last movement, not the storm! And that is the genius of Furtwangler. Everything is designed to lead to the full realisation of the unique depth of the finale. Of course, the storm is uniquely tense – perhaps unequalled in the entire history of interpretation – but the last movement, played at an extremely brisk tempo, is truly hallucinatory in its expressive power. Listening to it requires attention to two elements. The first is of a general nature, namely the flexibility of the conducting, which allows light to flood into this moment when the storm passes as if from nowhere, without us at first perceiving where this light is coming from. The second is very special: the pizzicati, which are unique in the entire discography – and which are as subtle as they are preponderant in the narrative.

There are several great, immense ‘Pastorales’ by Furtwangler. The first was recorded in 1943, in a studio, during the war. It’s a version that’s more interesting than moving to my ears, but that’s purely a personal opinion – although its context does make it rather special. Formally, the most beautiful version is undoubtedly that of 1954, in Berlin, in public. A truly outstanding version is that of 1944, also in public, which is so excessively dark and intense that I find it difficult to place in the spirit of the work – but that’s a personal opinion. The two that particularly interest me do so because they represent two sides of the same mountain. First we have intensity, in a vision resolutely anchored in the present moment, in 1947, for the return of the conductor to the stage, the light returning after the totally despairing vision of the war. Then we have 1952, a studio recording that has just been magnificently restored by Studio Art et Son, and which offers a lofty view and a solar lyricism. In my opinion, this is an extremely underrated version, although Furtwangler was able to adjust his vision to the singular experience of the disc.

Paradoxically, the Seventh actually causes me more problems than the Pastorale. For reasons of spirit, whereas, paradoxically, all the abstraction that Furtwangler introduces into the Sixth seems literally unnatural – no pun intended. In fact, it’s above all that the experience of the seventh directed by Furtwangler seems to me to run completely counter to my personal intuition. The Seventh is above all this sunny, alluring symphony, ‘the apotheosis of the dance’ – to quote Wagner – whereas Furtwangler turns it into a construction of ruptures, an experience of pain, and almost a cry – particularly in the Finale. When we listen to conductors like Carlos Kleiber, Hebert von Karajan, or even conductors who adopt slower tempi like Carlo Maria Giulini, or recently Gottfried von der Goltz, we don’t have the feeling of suffocating as with Furtwangler, we don’t have the feeling of being caught by the throat. It’s a symphony with a happy ending – as is often the case with Beethoven – and Furtwangler is alone in the opposite view. What’s more, it’s a symphony that offers an aesthetic experience of the purity of joy, with Beethoven finally notating the second movement ‘Allegretto’, not ‘Adagio’ as Furtwangler resolutely takes it. But after having disparaged it so much, I am nevertheless going to rehabilitate the Seventh to some extent through Furtwangler – because I have to. Firstly, Furtwangler makes the Seventh tangible, he makes it capable of producing a physical impact on the listener, making an instant impression. We are anchored in the present moment, nailed to it, imprisoned by it. Then, at the same time, Furtwangler reconstructs the narrative, he certainly does something else with it, but he modulates it as something that doesn’t allow us to anticipate anything, the story, the narrative is in the process of being created, of really coming to life in front of us. In short, it’s a vision that keeps us in a constant state of tension, deliberately surprising us and taking us elsewhere. So we have two immense versions of the seventh by Furtwangler. At the same time, this means that I can rule out the 1953 version, on Tahra or Deutsche Grammophon, which suffers from a heaviness that holds it back, and the 1954 version, on Orfeo, in which I find a touch of heaviness, to be honest, but that’s my personal opinion. Once again, we have two sides of the same mountain – Furtwangler’s ideas never, or almost never, change radically. On the one hand we have the 1943 version, in Berlin, in public. It’s an extreme interpretation, a race towards the void that crushes the spectator. On the other hand, there is the 1950 studio recording, in Vienna, which offers an absolutely fabulous sense of architecture and clarity.

So I won’t say too much about the Eighth, which to my ears has the same faults under Furtwangler’s baton as the Second, but with an additional element that escapes Furtwangler completely: humour. The Eighth is funny, and the aesthetic pleasure also comes from having fun! The orchestral fabric with Furtwangler is thick, and the musical discourse in the Eighth is already choppy to begin with, but with Furtwangler it becomes completely fractured. To compare with Furtwangler’s vision, I can only advise you to listen to Scherchen’s recordings, an extremely luminous version, full of humour – while Scherchen takes the symphony at an extraordinarily fast tempo, he decides to slow down in the second movement, There are also recordings by René Leibowitz, and even Karajan’s 1976 studio recording, which is paradoxically the most lively of his versions, because it is less overwhelmed by legato – there is also a very fine 1948 version, but let’s leave the Eighth there. And now for the final monument: the Ninth. It is a monumental vision in every sense of the word. Firstly, Furtwangler proposes an overall concept based on architecture, marked by very strong contrasts and total expressivity. This expressiveness is particularly evident in the way in which Furtwangler conveys his interpretation of the third movement so naturally, even though it runs counter to all convention. The depth of Furtwangler’s vision is simply dizzying in the Ninth. The tension and violence of the first movement are matched only by the clarity of the exposition of the themes – the Fugue! -The second is so urgent, caught up in a permanent tension, and the third is one of the most poignant moments in the history of performance. But what of the last movement? Is it possible to conceive of a vision that is a perfect representation of the race to the abyss? This is where Furtwangler’s interpretation begins to give me trouble. It’s obviously magnificent, with an evocative power beyond measure, but is it really in keeping with the spirit of the text, if we can even know what Beethoven had in mind (which seems complicated because he died a while ago, after all)? I don’t know. In any case, Furtwangler pushes the Ninth to its limits in a way that no conductor has ever done, and yet what emerges is a great clarity and immense unity. This is certainly a far cry from a sunny version like Masaaki Suzuki’s extraordinary recent recording, but I find it all the more interesting because I think we can assume that he listened carefully to Furtwangler, as did other great interpreters of the Ninth, like Frans Brüggen, for example – except that Brüggen remains dark like Furtwangler, and no one can possibly match Furtwangler’s level of expressiveness and evocative power, so I think we can stick with Furtwangler’s interpretation from this point of view.

But, to return to Furtwangler, since comparison is not reason, we have a number of versions of the Ninth by Furtwangler, which are very different and all worth listening to. First we have the 1937 London version, which is splendidly clear and really deserves more attention. Then we have the two versions from Berlin in 1942, one much better recorded than the other. The vision of war is truly extreme, but it is an absolutely unique testimony to Furtwangler’s art, the ‘desperate cry of a musician in the midst of barbarism’, in the words of Sir Simon Rattle. My favourite is undoubtedly the one from 1951, in Bayreuth, because I think it is the best synthesis of Furtwangler’s vision of the work. I should also mention several superb versions with the Vienna Philharmonic, in 1951, 1952 and 1953 – the latter having been published by Orfeo and Deutsche Grammophon. Furtwangler returned to conduct the work in Bayreuth in 1954, in a less tense vision than in 1951, and finally conducted it in Lucerne, some time before his death, in an interpretation that almost looks to the beyond, as Christophe Lambinet reminded us in an episode of the podcast ‘L’enregistrement qui m’a marqué’ (The recording that made an impression on me) and which is available on the SWF YouTube channel, a podcast that I highly recommend.

That brings us to the end of our journey through Furtwangler’s vision of Beethoven’s symphonies. From now on, I propose to try and identify certain cardinal points that unite and constitute the essence of Furtwangler’s apprehension of Beethoven’s symphonies, using musical examples.

I mentioned in my introduction that humanism is the first thing that springs to mind when we talk about Beethoven, so let’s come back to that. Beethoven’s music, insofar as he is perhaps the composer whose music is most infinitely human, obviously also has its moments, its phases of darkness, its darker corners, its shadows. But darkness never invades Furtwangler’s Beethoven, and the conductor always fills the dramatic movements with a drama that is never overplayed. There is a theatricality, a dramatism in the original sense of the word, a dramatic dimension one might say, but sincerity takes precedence over what seems feigned, and in this it is lyricism that seems to predominate over lamentation. Speaking of lamentation, this may also remind us of certain portamentos, very much in evidence in tragic or at least slow movements, which become affected in other conductors belonging to the same interpretative tradition as Furtwangler, such as Willem Mengelberg, for example. Mengelberg is always looking for lyricism, but he puts so much emphasis on his intentions that it becomes either well-handled or, more technically, very segmented, and we end up on the side of division rather than continuity – which in Romantic philosophy is a heresy, by the way -, Furtwängler remaining, I think, much more coherent than Mengelberg – at least in Beethoven, and I think in general, but that’s my opinion.

This humanism is embodied particularly well in the way Furtwangler conducts the Fifth Symphony, keen to represent the different facets of the human spirit, in all its complexity, singling out its particularity.

However, for all the capacity for empathy that permeates the performance, this humanity is also that of a man lost in the wrong times. Furtwangler has often been described as a nineteenth-century man born too late, and I tend to agree. It is perhaps this post-romanticism that distances Furtwangler from the light of Beethoven’s works: Furtwangler conducted Coriolan with a darkness that no one else knew how to achieve, or perhaps even wanted to, and he never conducted the Missa Solmenis.

Furtwangler’s forays into Beethoven’s music sometimes seem to involve a form of solitude, but this solitude is always deeply embodied, organic even. The questions, however serious they may be, respond to each other to form what might almost be likened to a path of elevation. This solitude is truly romantic, then, for all the metaphysics it carries in its wake, and which it expresses with all Beethoven’s sincerity. Undoubtedly, Furtwangler’s music was also profoundly romantic in its ability to inscribe metaphysics and ideality in an orchestral material that seemed to be caught in a permanent crackling – something I already mentioned in the studio recording of the Fifth Symphony, in 1954.

This solitude does not cry out, or at least it retains a form of restraint in its expression, a restraint that finds its catharsis in bravura, in the sense that it uses it as a space of liberation. This is how I suggest you read this aspect, even if it is purely hypothetical and I’m afraid will never be resolved, the way Furtwangler conducts the ‘Eroica’ symphony, the second movement of which, the Funeral March, is as follows:

In Furtwangler’s interpretation, Beethoven is sensual, sometimes even carnal, and this is evident in the way the conductor coherently links the symphonies’ atmospheres. But this is perhaps a constant in Furtwangler’s art, to be found in Beethoven’s works as elsewhere. But above all I propose a slight incursion outside the symphonies, to talk about a relationship that tells us a great deal about Furtwangler.

The pianist Furtwangler most admired was Edwin Fischer. The two artists share this idealistic and metaphysical vision of Beethoven, and it’s an osmosis, an enchantment, that we feel particularly well in the ‘Emperor’ Concerto that they recorded together in February 1951, in the wake of a concert of which we unfortunately have no archive – the beard! -. Furtwangler and Fischer complement each other wonderfully here, giving the concerto an ever-renewed energy, luminous and profound, and above all a lively and triumphant vision.

Here, it is, and it should be remembered that this is far from always the case with Furtwangler, light triumphing over darkness; it is a romantic interpretation in the almost philosophical sense of the word, in that it moves further away from chaos with each additional note.

But there’s one document that I think is essential if you’re interested in Furtwangler’s relationship with Beethoven, and if you speak French you’ll find it translated here. This document is an extract in which Furtwangler explains his conception of the Fifth Symphony on French radio, to Fred Golbeck, in 1953.

As we have already seen, Beethoven’s Fifth was the work Wilhelm Furtwangler performed most during his career. He remains an immense interpreter, perhaps the most influential of the twentieth century in a sense, and we are going to see his influence on the conductors who followed, and who in one way or another took after him. And to explain his interpretation, I suggest you read the conductor’s own vision of the work, in April 1953, in this famous interview with Fred Goldbeck:

English translation:

‘Let’s take a well-known example: Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, the first movement; it’s made up of three thematic elements. Several different performers, with their different breaths, tastes and temperaments, may play in different tempi, heavier or lighter; but, for an interpretation to be right, one thing must always be the same: the thing that makes the details cease to be details and enter, through their lighting and their relationships, into a higher unity. In our example, this is the relationship between the three thematic elements. The first must have the violence and grandeur of Beethoven:

[ Musical example ]

the second should have the smile and tenderness – and I would almost say the innocence – of Beethoven:

[ Musical example ]

the third is the most difficult to put in its exact light; it seems more neutral: a cadential formula, almost conventional:

[ Musical example ]

But it must, because of its significance in the movement as a whole, have that character of definitive affirmation, of triumphant sublimity, which gives the other two themes their conclusion and their true meaning. But I don’t think there are any different ways of conveying this relationship between musical ideas, which in Beethoven’s case is even more important than the ideas themselves.

And this is where the performer’s attention should be focused. His interpretation will then have two advantages: it will make everything perfectly clear to the listener and it will be perfectly natural. These two elements, clarity and naturalness, are the two main rules to follow in order to achieve good interpretation.

Having seen the depth of Furtwangler’s interpretation directly, let’s talk about his influence on several of the great conductors of the twentieth century. First, let’s listen to one of the performers who learned most from Furtwangler, and who has been said to be perhaps the perfect synthesis of Furtwangler and Toscanini, far more so than Karajan, Carlos Kleiber, for whom Furtwangler was the main inspiration along with his father Erich, whose style differed enormously from Furtwangler’s. Here, then, is Carlos Kleiber conducting the opening of the Fifth Symphony, in Chicago in 1978:

Carlos Kleiber is undoubtedly the only one to really take literally the meaning that Furtwangler gave to the three motifs at the beginning of the movement. First there is the very sombre attack from the first chord, then the rebound as it develops and finally the extension of the energy in the brass almost to nothingness. The violence is in the overwhelming, alert vivacity, and the grandeur in the dark atmosphere that seems suffocating from the outset. The transition to the second motif is absolutely magnificent, extraordinarily coherent, allowing Kleiber to gradually sketch out that smile and bring out, elevate that innocence. Finally, Kleiber uses his really fast tempo to bring the cadenza to the point where it almost – if not quite – becomes a dance, and we find again the bounce that has animated the interpretation since the entrance.

Kleiber is also a genius as a conductor, because if the details cease to be details, which is what makes an interpretation right according to Furtwangler, it is because the conductor takes them into account in their particularity in order to integrate them into the whole through the factors that ensure coherence, in this case the bounce and the tempo – it should be noted that the tempo is unchanged here, whereas Furtwangler is constantly varying it.

Another of Furtwangler’s great heirs is Herbert von Karajan, although Furtwangler hated him. For reasons that are well known, he had a certain animosity towards ‘Mr K’… Furtwängler was for Karajan ‘a whole world’, ‘his appearance [having] always accompanied him in [his] career, in [his] activity’, as he himself explained, in a text that can be found in a circular from the Furtwangler Society, called ‘The Master’s Workshop’, before defining Furtwangler’s art as follows: ‘It was really characteristic of him that something would fade away and then, from the silence or momentary calm, something new would develop. These were moments that had an unusual power of expression with him. And then he would do something admirable, as Siegfried Borries, who was Konzertmeister when I took over the Berliner Philharmoniker and who had worked with him all the time, told me: ‘You know, in those moments, you suddenly had the impression that he was looking for a way out. He was looking for a way out of the uncertainty, he was trying to find a new interpretation »: That’s how it was with him, it wasn’t a search and an invention, but it was truly the disappearance of one thing before something else already existed. This shows what was important to him, what was, after all, a fundamental situation in life: a new decision after doubt. And you can always see it in him; whether in the transition from the third to the fourth movement of Beethoven’s Fifth or elsewhere, it was always the same thing.’

So I suggest you listen to Herbert von Karajan’s version, here in 1977 in Tokyo, because overall I find Karajan more interesting in public than in the studio :

Once again, a very dry attack in the first chord, perhaps less sombre than in Carlos Kleiber’s version, although just as violent. The brass are perhaps more brilliant, even if less virtuoso than those, obviously, of the Chicago Symphony that Kleiber conducted.

Karajan’s music is undeniably violent, grand, almost powerful, something that Furtwangler was not looking for. But if Karajan, with his seemingly innate sense of the orchestral instrument, does not manage to give all the light that Beethoven’s tenderness requires, he perfectly restores the cadenced aspect of the third motif. But Karajan’s coherence is a factor of unity, meaning that, as with Furtwangler, the orchestra is conceived as a whole, and in this respect the most important thing is achieved, because the details cease to be details and become part of the superior unity so well evoked by Furtwangler.

Finally, let us add that Karajan greatly admired Furtwangler, and this can be heard particularly well in Brahms’s First Symphony, as I said in the episode on Brahms, whether in 1959 in Vienna, or in 1988 with the Berlin Philharmonic in London. But now I suggest you listen to another version, at first sight much closer to Furtwangler’s vision, but to think of it that way would actually be a bit of a trap:

This version by Eugen Jochum that I wanted to talk to you about dates from 1945, and it is also with the Berlin Philharmonic. Suffice it to say that this interpretation is inevitably imbued with Furtwangler’s art. And that’s understandable, as this recording is similar in many respects to the Fifth given by Furtwangler in 1943. However, it should be noted that there is none of the metaphysical grandeur that Furtwangler always gave to the Fifth, and that the Fifth of the war, that of 1943, is not Furtwangler’s most complete, in the sense that it lacks innocence and has lost its smile – and for good reason. But Jochum’s version lacks the metaphysics that take Furtwangler’s interpretation into a higher dimension, so in a way it remains nothing more than a heap of violence and darkness. But of course, the orchestra sounds magnificent, the lines are legible, very clear even, and there is a beautiful coherence. But in the end, where Furtwangler’s choices, for example the stretching of chords until they become suffocating, in order to bring enormous energy, were powerful and full of meaning, taken up by Jochum they seem perhaps a little vain. In fact, you get the impression that Jochum is imitating Furtwangler’s mannerisms, and I think you can generalise that to the great conductors, that to reproduce their mannerisms is to systematically fall into bad taste. The last version I wanted to talk to you about concerns a performer who had immense admiration for Furtwangler, even though he plays on period instruments, and that is Frans Brüggen:

What has obviously been passed on from Furtwangler to Bruggen is above all his great expressiveness. Bruggen knows how to give a lot of substance to his interpretations without it sounding heavy. In fact, Furtwangler is never, strictly speaking, heavy in the fifth; even in his 1954 studio work, which is very slow and even heavy, there is an absolutely perfect balance.

In a way, it might seem surprising that Bruggen’s version is a historically informed one, a version on a period instrument, and yet this interpretation is truly personal. This is first apparent in the darkness that already runs through these first, albeit lighter, chords, which then accompany a development that breathes a great deal. Bruggen learned a great deal from Furtwangler about the essential role of breathing if you want to keep the tension intact. And it is also in this way that Bruggen’s conducting is truly organic.

Then, with an absolutely sparkling art of transition, Bruggen announces the second motif in all its brightness and brilliance, without being too extravagant either. In fact, Bruggen’s entire version is formidably balanced and natural, and this is particularly noticeable in the last cadenced motif, which despite its rather slow tempo remains above all very spontaneous.

What’s very interesting about this case study is that we can see very clearly what has been passed down, and it highlights how the great conductors who inherited the work, or who in any case learned from Furtwangler, managed to come up with their own, truly singular interpretation, while retaining the essential spirit of the Fifth Symphony as well as the lessons of Furtwangler’s vision, which shone through in his interpretations. In each of these interpretations, with the possible exception of Jochum’s, the details cease to be details and become part of an overall coherence and a remarkable unity.

And now back to Furtwangler? I’d like to conclude with a personal opinion. In fact, I think that Furtwangler is as brilliant as he is problematic in his approach to Beethoven’s symphonies. He is brilliant both in terms of the aesthetic appreciation we can have of all his performances and in terms of his legacy, or at least the influence he will have on so many conductors, which I’ve tried to show you just a little, because there’s no time and it’s already too long, and problematic in the sense that he poses a problem. My question, rather than a real reservation in reality, is based on the fact that Furtwangler seems to be applying an interpretative heritage that is very much later than Beethoven’s. It’s a retrospective vision that seems to obscure an essential part of the inspiration that drives Beethoven’s music. In fact, Furtwangler’s vision is partial, and this makes it fabulous as much as it weakens it. Furtwangler truly reveals, in the sense that it really is a revelation, Beethoven’s symphonies in all their depth and the vertigo of their writing and scope, at once complex, sensitive and metaphysical, but would he be the conductor I would recommend to a neophyte to discover Beethoven’s music? Certainly not. And I have done so with some experience, some practice of Beethoven’s symphonies by Furtwangler, whom I have listened to and cherished for eight years now, and whom I hope to listen to and cherish for a long time to come. Furtwangler’s discographic legacy in Beethoven is profoundly moving for me, because it bears witness to an absolutely unique vision – it is completely impossible to even attempt to reproduce it – of a total conductor who nonetheless traced a singular path in what remains perhaps the greatest symphonic corpus in the entire history of music.

Laisser un commentaire