When we talk about a pianist who plays in a truly « pure » way, in the sense that nothing is altered, in other words, nothing is superfluous and everything serves the music, I think of Alfred Brendel.

Born on 5 January 1931, Alfred Brendel left us on 17 June. He was universally respected for his interpretations, particularly of the music of Beethoven, Liszt and of course Schubert, but also for his activities as a poet and his books on music.

After winning the fourth prize in the Busoni competition in 1949, the pianist began an international tour and played with the greatest conductors of his time, including Herbert von Karajan and Eugene Ormandy. Even though he was largely self-taught, Brendel’s influences were many, including Cortot, Schnabel and Kempff, and the master classes given by Edwin Fischer in Lucerne between 1949 and 1960, which Brendel was able to attend.

Brendel’s playing was undoubtedly characterised first and foremost by the omnipresence of light. It is thus clarity that becomes insight, illuminating each work with a new radiance and presenting each composition with a clear outcome. In Brendel’s interpretations there is a form of ascendancy, or at least a perpetual quest for clarity, and this also makes it possible to reveal the works in a new, rather than original, light – Brendel’s interpretations are in this respect more unique than original, there is no search for effect in order to stand out.

When one thinks of Schubert’s ‘Winterreise’, one does not necessarily think first of the light, rather of the very dark murmur that accompanies the romantic traveller on his journey through the cold. But Alfred Brendel’s interpretation, with the immense Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, illuminates the whole work with a real winter sun, without being too pale, with just the right amount of contrast.

Alfred Brendel’s interpretations are always very inspired. They are often even illuminated by what might be described as a form of joy, in the true sense of the word. And it is this joy that allows Brendel to reconcile the sometimes very different aspects of the same work and, beyond preserving a certain coherence, truly give the work meaning. It is therefore once again what one might call a quest for light that binds Brendel’s interpretations together.

I suggest you listen to this embodiment of joy in Brendel’s performance of Beethoven’s Hammerklavier sonata.

Alfred Brendel’s clarity allows him to develop a very rich sound, with a wide range of colours and many nuances, some of which seem to be specific to a particular interpretation. This sonority combined with a detailed and ample phrasing allows the pianist to reveal details that are never anecdotal: once again, everything has its meaning in an Alfred Brendel interpretation.

Even if it is far from being the extravagance that characterises the Austrian pianist, the humility and sobriety that are omnipresent in his style nevertheless allow him to demonstrate an absolutely outstanding creativity. Simply, the choices he makes always seem natural, even obvious.

In his interpretation of Haydn’s Sonata in B Minor, Alfred Brendel brings out all the complexity of the piece in a clear and obvious manner. Yet the interpretation is far from being devoid of all the lightness and even humour that characterise Haydn’s music, as can be heard in the first movement.

Alfred Brendel’s search for clarity is accompanied by an art of phrasing and counterpoint that converge in an almost absolute search for balance. The nuances are thus pronounced without the need to add to them, there is no need to make an already sufficiently complex subject difficult, so much the better to serve it with simplicity, with evidence, with all the nobility that these qualities imply.

It is therefore a form of humility in front of the work that characterises Alfred Brendel; it is truly the interpreter who puts himself at the service of the composer. Indeed, although the pianist possesses an extremely personal style, he does not put it before the composition, but rather puts it at the service of the work in its uniqueness, in order to better reveal what makes it complex, original or, more simply, its character.

Schubert’s first Impromptu D.899 has often appeared dark or tormented, but Brendel is perhaps the only one to find a luminous way out. In an interpretation that is exemplary in its purity, the pianist emancipates himself from the tragic while retaining the dramatic aspect, in the theatrical sense of the term.

Alfred Brendel’s interpretations are thus more often intellectual or Apollonian than sensitive or Dionysian. Even the most cathartic or simply romantic works do not require any additional effect. In fact, Brendel seems to let the work speak for itself; he is content to underline this aspect or highlight that passage.

The third movement of Schumann’s Kreisleriana thus appears in Brendel’s interpretation to be truly essential, pure in the sense that it is the music that seems to build itself up as it goes along, as if the pianist were a sculptor who is content to model a work that speaks for itself, and which becomes truly organic as it develops.

Perhaps the greatest feeling one gets from listening to an Alfred Brendel performance is a kind of soothing solitude, despite all the torment the piece may imply. If Brendel’s playing is not the one that most embodies the material, the journey that the pianist builds up during each of his interpretations plunges the listener into a form of interiority and reflection of rare intensity. Brendel thus magnificently alternates the climates and internal tensions of the works he performs.

Alfred Brendel thus combines a certain dynamism with several variations of atmosphere with an almost total naturalness in his interpretation of the first movement of Schubert’s Sonata D.894. One feels completely at ease with this solitude. Brendel reveals the sonata’s metaphysical dimension without the need for Richter’s slowness or heaviness: Brendel’s interpretation is not serious or austere, but it is no less profound.

Brendel is one of the contemporary performers who has most influenced my conception of what music can be. His books are an inexhaustible source of inspiration for all lovers of music in general, and his interpretations will forever be immortal. I am deeply touched by his passing, and grateful for all that his work has contributed to my life as a music lover.

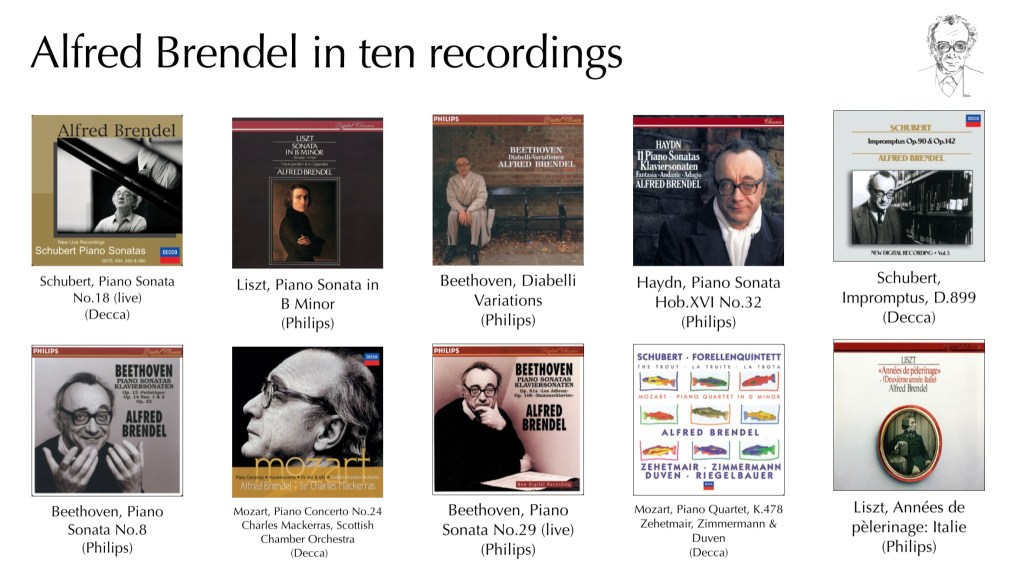

By way of an opening rather than a conclusion, here are the ten recordings that made me realise the genius of Alfred Brendel: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLwovaEVoT1mLnJluj74YpQZBiR6HW9_3P&si=BkUj6xZgMtuYCOSJ

Laisser un commentaire