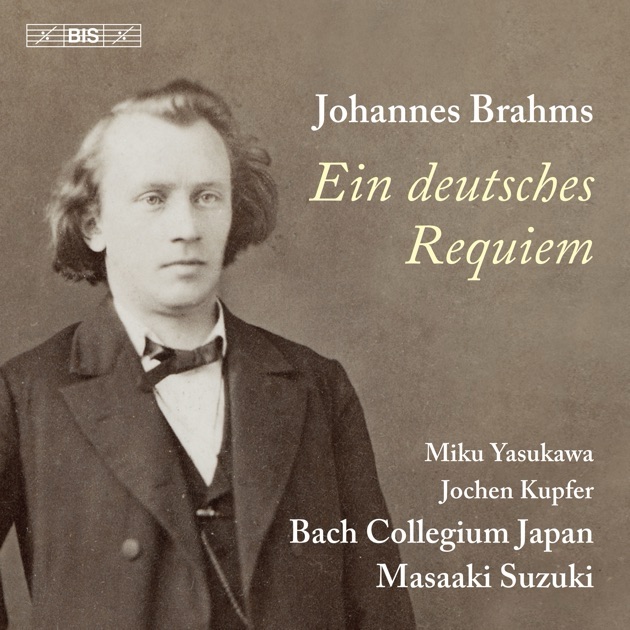

Masaaki Suzuki conducting the German Requiem. Miku Yasukawa, Jochen Kupfer, the Bach Collegium Japan. And a masterpiece. Suzuki and the Bach Collegium Japan have already produced a Mass in B Minor of sublime lightness, a Johannes Passion of total commitment – recorded live in Köln -, without doubt the most beautiful Christmas Oratorio ever recorded, a splendid Ninth Symphony by Beethoven – the greatest recorded since Frans Brüggen – , an immense Requiem (perhaps the most moving ever performed) and the finest of Mozart’s Great Mass that I have ever heard.

The German Requiem is that often monumental work, the sacred mountain that Furtwängler, Karajan – several times -, Klemperer and Kempe climbed by force. Some, such as Herreweghe, have sought and found another way, through research into the historicity of the work. But had we ever heard anything like what Suzuki delivers at the head of his orchestra, and of course his choir? An overture that emerges from nothingness as Furtwängler might have conceived it, letting the lightness of the lines speak for themselves, underlining the points of harmony. The harp! Everything began to rise even before the choir entered. The legato is sovereign, the lightness of the orchestral fabric preserves the dialogue of the voices. We are simply out of time! The melody takes centre stage, carried by a crystal choir. There’s something vaporous about the strings, and every counterpoint is perceptible. The Selig sind, die da Leid tragen almost sounds like a Bach’s Motet. In the Denn alles Fleisch, es ist wie Gras, Suzuki finds even more tension, colouring the brass with extraordinary nobility. What’s more, the tension is built up by the support of the strings and the almost subterranean emphasis of the brass. There is a remarkable continuity in the melody, the detail serving the unity of the discourse.

The work becomes more tragic, and also more vertical, losing its telluric force in favour of a more solar expression, the Apollonian triumphing over the Dionysian. And here again, all along the whole work, the harps! The crescendos carried by the singing brass in the background to increase the tension through the strings are absolutely grandiose. Balance animates the central movements, while preserving the necessary contrasts. The amplitude of the gesture lends a vigorous sparkle to the attacks, and there’s no end to the rise, again and again (the end of Herr, lehre doch mich touche is absolutely dizzying)! The legibility of the lines and the dialogue between the voices in Selig sind die Toten is absolutely admirable, giving a sense of timeless significance. And then, that melody given to the woodwinds at the very end! Basically, we can no longer date the work, which is strangely positive! At least, this Requiem become inactual! We’re certainly not far from Fauré’s Requiem, but what beauty (and not just formal beauty)! This work, which so often has to cope with length, with a telluric monumentality that sometimes crushes it under its own weight, rediscovers a confounding naturalness. The force is no longer the horizontality that sweeps away as it expands, but a spiritual elevation! A splendid performance, a new benchmark in a vision that is more celestial than the fervour of Philippe Herreweghe’s interpretation, but which has nothing to envy Karajan, Furtwängler, Kempe or Klemperer. We can’t wait for Masaaki Suzuki’s next appearances at the head of his Bach Collegium Japan – among them Fauré, which we hope for with all our hearts.

Laisser un commentaire