It is true, Wagner past his conductor life a to make the adversary of Mendelssohn, apostle of an approach all in vivacity and light tempi. No, Wagner was not an advocate of fast tempi, any more than he was an advocate of lightness. But what Wagner wanted above all was to place singing at the centre of the musical discourse. Wagner’s opera was described by its author as a « musical drama », with very intense diegetic and musical stakes. Wagner therefore aspired to a certain balance, the one that can allow singers to fully bloom, as the opera was before all their expression place to them. However, Wagner itself convened that if what is the in the first place the singers, and consequently the conditions that put the in the best possible provisions, certain approaches are prefers to other. The question is: which of these approaches is the one that best allows the singing to flourish? And, as a Wagnerian music lover – and, I insist, nothing more – I tend to think that the approach that best leaves room for singing, the one that revolves around the balance that must therefore be sovereign, is the one that favours lightness and liveliness. However, it is obviously not play Wagner in the style of Mendelssohn – yet, in the background, I think I would really like it, but this is not very correct to admit it. What I want to talk about in this article is why conductors who place lightness and liveliness at the center of their approach when they conduct Wagner are the ones whose art moves me most personally, and beyond that it is the approach that best allows the lyricism to flourish and the text to sing, and, of course, the singers to sing in the most beautiful way.

But talking about lightness, before the examples I’m going to talk about next, requires a little clarification. Although the definition will take care of itself through the musical examples that follow, I have written this article based on an opposition, that between lightness and heaviness. Kundera wouldn’t pit them against each other in real life, but here we’re talking purely in theoretical terms about music. It should be remembered that the distinction between lightness and heaviness is obviously primarily theoretical, and must therefore be qualified. Of course, any balanced approach borrows from both; it even needs both, and that’s precisely what’s needed if balance is to be achieved. But there is often – not always, especially in the case of Furtwangler – a dominant one. Finally, I’d like to say that this review is based above all on my listening, which is by definition subjective. Nothing can be absolute, and I have absolutely no wish to be dogmatic. So let’s get on with it!

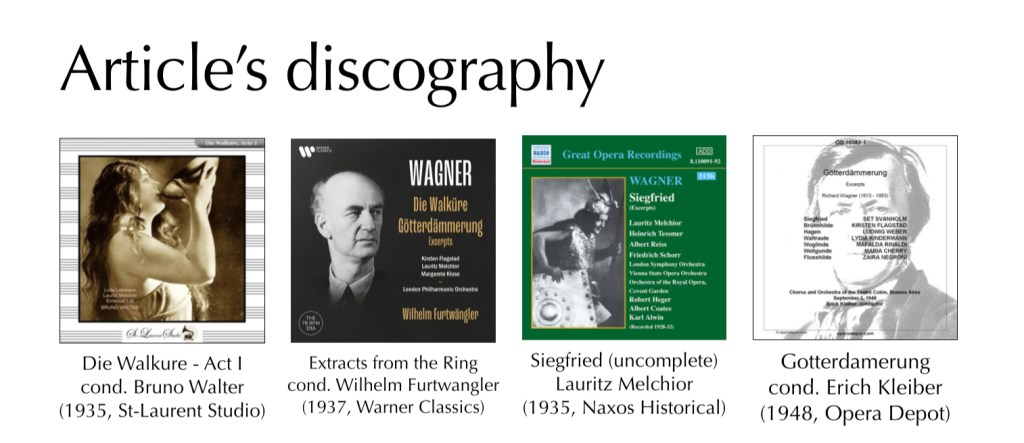

The first example I’d like to talk about is actually a comparison, between two approaches that have their obvious points in common, as well as their fundamental differences. However, it should first be pointed out that the sound, which is heavily degraded, can have an impact on the analysis. These are recordings from the Golden Age, and live ones at that. Let’s compare the conducting of Artur Bodanzky and that of Erich Kleiber. The former has often been recorded at the Met Opera in New York, the latter at the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires. Both chose rather similar tempi, but it was their way of modulating the expressiveness of the phrases that changed radically. Bodanzsky used very fast tempi to allow the singers to be as melodic as possible in their phrasing. So, even though it is extremely fast on the whole, it is on the whole rather smoothed out towards lightness. What’s more, the Met Orchestra’s orchestral sound does not support the lyrical expressiveness of the conducting.

Erich Kleiber, for his part, used the rapidity of his tempi to emphasise many accents, amplifying the dramatic dimension of Wagner’s narration, without ever going overboard, either by letting the orchestra overwhelm the singers or by demonstrating contrasts. But what allows Erich Kleiber to create such tension in the musical discourse and to emphasise the expressive contrasts so much, while allowing the singers to have their say, is the lyricism of his conducting. Bodanzsky accompanies, and he does so extraordinarily well – undoubtedly better, for my taste at least, than Erich Leinsdorf at the same time, for example, because he is both just as natural and, above all, his conducting is far more taut – whereas Erich Kleiber magnifies every detail of the score – and even then, you can tell at times, as the sound quality can be catastrophic. There is a sense of balance in Kleiber, which allows the discourse to be immensely natural. But, in any case, what makes both Bodanzky’s and Kleiber’s interpretations natural is the speed of the tempi, and the lightness that follows.

And as we have seen – or rather heard – with Erich Kleiber, the lightness of the conducting does not prevent intensity; on the contrary, this thin orchestral fabric magnifies the timbres and allows the orchestra’s colours to become expressive in their own right. This can be heard particularly well in what remains perhaps the greatest achievement in the history of conducting on record in Wagner: Die Walkure, recorded in 1935 under the baton of Bruno Walter – but only the First Act. And this time the recording is good, excellent even (I recommend the Studio Saint-Laurent edition, unapproachable). This disc has everything I want to talk about in this article. First of all the lightness, of course, which allows the strings and woodwinds of the Vienna Philharmonic their unique colours, the brass their drama as well as their finesse, and the timpani are rather restrained. The tempi are lively, but above all they are much less hurried than those of Bodanzky and Kleiber – but these are live performances, let’s not forget. And so this introduces an essential characteristic of Walter’s conducting in this recording: the attacks are sharp, clean, precise, but above all none of the snatched violence that characterises the visions of Bodanzky and Kleiber.

And the validity of the light-hearted approach to the Wagnerian orchestra is perhaps further confirmed by Furtwangler’s approach. Indeed, Furtwangler was the embodiment of post-romantic conducting, with its expressiveness, its sometimes truly radical variations in tempo, its reliance on intuition to directly influence the listener’s perception. And it was with this aim of conveying the theatricality, the above all lively character of Wagner’s musical drama – the expression was coined by the composer himself, who rejected the term opera – that Furtwangler once again adopted a light, lively, alluring approach, and at the same time one of incredible intensity. Furtwangler performed the Ring at Covent Garden in 1937, and several fragments of it have survived. First of all, Act III of Die Walkure, where the orchestra literally flies, with flights of fancy and an extraordinary dialogue between woodwinds and strings in the Ride of the Valkyries – and brass in the background, which has perhaps never conveyed so well the literally suspended aspect of this moment in the drama. Note that Clemens Krauss, in 1953 at Bayreuth, played the passage with the same type of intensity, i.e. with strings and woodwinds in the foreground, and brass in the background, simply marking the rhythm, and varying the strength given to the desks in order to initiate variations in the musical tension. Next, Gotterdamerung, for which we have the entire Immolation, perhaps the most beautiful of all, with Kirsten Flagstad, and above all, therefore, the complete burning of Walhalla. And what does Furtwangler do in this passage? First of all, he doesn’t hesitate to speed things up, which doesn’t have the effect of rushing things, but of giving the feeling of the urgency of the moment. At the same time, he doesn’t hesitate to subtly play on contrasts to surprise the audience, and the speed of the tempi helps to give momentum and an auditory vision – a little incoherent, but in this case you get the idea – of the Rhine continuing to flow. Furtwangler’s vision is therefore extremely figurative, and largely as sensitive as it is metaphysical. Furtwangler was perhaps the conductor best able to apply the Wagnerian precepts of interpretation to the composer’s works, because he placed flexibility and suppleness at the centre of his vision.

So what about the more – at least in appearance – ‘traditional’ interpretations? First, we must return to Furtwangler, and this time to his Tristan, from 1952 (Warner Classics, recently remastered by Studio Art et Son). Indeed, this time there is slowness, but more than heaviness on it is weight. In fact, Furtwangler seeks to make the orchestra weigh on the listener, which is how he should feel. To open the Prelude to Act III, Furtwangler does not hesitate to introduce enormous intensity in a very gradual way within the same phrase, which has the effect of giving absolutely enormous scope and amplifying the dramatic stakes here too. The feeling is exacerbated – and Furtwangler a post-romantic, and undoubtedly a man of the nineteenth century. Hans Knappertsbusch, on the other hand, applies an interpretative schema that is not based on how the listener should feel – which is why Furtwangler’s style is extremely flexible, even though it shares many common ground – but on the music itself, on music as flow. There is a kind of force, more or less quiet, more or less thick, more or less intense, depending on the moment, that moves forward and illuminates each passage one after the other. In this sense, the coherence of the approach ensures the coherence of the interpretations. However, for my taste at least – it’s obviously a matter of taste when one interpretive approach is legitimised over another – this gives Wagner’s drama a form of irregularity, of inequality in terms of what’s at stake depending on the passage. And I don’t think that this is in any way the most justifiable, insofar as Wagner precisely privileged the singing and gave the singers pride of place, which is contrary to Knappertsbusch’s interpretative scheme, in which, in application, the orchestra often goes over the vocal lines. However, I have deliberately overlooked an absolutely fundamental aspect when talking about interpretation: the spirit of the interpretation. Knappertsbusch’s vision does not always serve some of Wagner’s works to the best of advantage, but it does magnify others. The character of Parsifal as a sacred and spiritual drama is thus emphasised, albeit to the benefit of a more human approach – like that of Clemens Krauss, for example – and it is this whole dimension of the work that will be at the centre of the discourse, and the whole vision that we will have while listening to it will revolve around this centre of gravity.

Finally, some of the performances straddle the line between lightness and heaviness. And it is interesting to note that while these may appear to be the most balanced, they are not the ones that best convey the issues, the tensions of the works, and above all the lyrical dimension, the singing that is so essential. The most famous example of this is Herbert von Karajan, the conductor who has so often been portrayed as being on the perfect borderline between Furtwangler and Toscanini. Incidentally, speaking of Toscanini, it is interesting to note that this conductor, who is usually so lively and even sharp, is so slow and ponderous in Wagner. Having closed this parenthesis, we need to open a second one to say how much closer Karajan was in reality to the art of Furtwangler than to that of Toscanini, and that conductors like Guido Cantelli or Carlos Kleiber were much more at the crossroads of the stylistic approaches of Furtwangler and Toscanini. But back to Karajan. His quest for balance is, in fact, a position that, when I listen to him, often seems untenable. In the 1950s, particularly during the « New Bayreuth », Karajan conducted a balanced Wagner. And it was magnificent!

There is fullness and roundness, but there is also drive and liveliness to balance it all out and make it natural, so that the singer can fit melodically into this flow: everything sings. But very quickly, from the 1960s in fact, Karajan began to favour legato, an expressiveness based on the roundness and gleam of the orchestra rather than on rhythm. And, in the end, he lost the rhythm completely – you can still find it, although you sometimes have to make an effort to find it, in Rheingold, but you’ve lost it for good in Gotterdamerung. Where Karajan’s very gleaming style in Wagner, in a very demonstrative sense, was happily applied was in the Meistersinger, lyrical both in 1951 and in 1974 in Salzburg.

Another conductor who favoured a balanced approach was Rudolf Kempe. And this approach is much more convincing to my ears than Karajan’s, for a simple reason really. Where Karajan dulled his attacks, Kempe’s gesture is still lively, his attack always clean, and this is what enables him to maintain a certain profusion and great richness of timbre, and even a kind of soft carpet, in his interpretations of Wagner. His Lohengrin is a fabulous example, as is his Ring at Covent Garden.

If balance therefore seems to be the supreme good of Wagnerian interpretation, the means of achieving it seems inevitably to involve a form of lightness, which allows lyricism to be introduced into the equation, an essential component of an orchestra that gives pride of place to singing. Moreover, clarity is also what allows the leitmotivs and the different centres of gravity in Wagner’s musical drama to develop. I could have mentioned many other interpreters – starting with Carlos Kleiber, perhaps the most balanced of them all, although he has only conducted Tristan – but I think that those presented here offer an overview of approaches that include various forms of lightness in Wagnerian interpretation.

Laisser un commentaire