Schumann’s Fantasy is a work truly apart in the composer’s oeuvre. It is perhaps the least illustrative and the least programmatic of the composer’s works, but the most contemplative as well as the most passionate. Composed in two distinct phases – first the first movement, to be played with intensity and passion, composed for Clara, before the addition of the next two, one more dance-like, initiating a repetition before the last, one of the summits of Romanticism, It is sometimes difficult, however, to grasp their unity at the same time, sometimes feeling as though we are listening to two meditations whose intensity is cut short by a dry movement that is too light in comparison with the two behemoths that surround it. Yet this – unpleasant – impression is far from being felt too often. In fact, the Fantaisie is one of the most recorded pieces in the piano repertoire, and its discography is – extremely – consistent.

Annie Fischer’s harsh, painful, sometimes even violent vision is a journey strewn with pitfalls and torments. What’s more, Maria Yudina – despite the very precarious nature of the sound recording – takes the Fantaisie towards the expression of an absolute, on the brink of death, in a vision that is properly mystical rather than spiritual, and above all not material – sensitive support becoming a form of condition for expressing the absolute in question, in an interpretation that will perhaps provoke a feeling of disgust in some listeners. But sometimes the dishevelled, painful and violent dimension loses its authenticity, with performers who use it to evacuate the affective – emotional – depth of the work. This is the case with Sviatoslav Richter, whose vision has more to do with demonstration – albeit a very successful one – than with the reality of feeling. Basically, we attend the work with the awareness that we are seeing – or rather hearing – a performance, and we remain somewhat outside Richter’s discourse. But the excess of formalism is also to be found in the opposite vision, i.e. in the attempt to make the Fantaisie too smooth a work – perhaps the intention of coherence is sometimes transformed into a desire to push into the background the opposites that nevertheless run through the work. Youri Boukoff’s version is carried along by a certain naturalness, although the attacks sometimes lack relief. Alexis Weissenberg gives a rather pearlescent performance, but it too lacks a little relief and body. Marc-André Hamelin, on the other hand, offers a relief, albeit with a few effects – but the whole remains fairly natural. A much more personal version is that of Radu Lupu, in a live recording from 1994, very clear and raw. The discourse is sometimes analytical, but the attention to detail is constant, with an absolutely enormous sound. There is also a certain exteriority to Wilhelm Backhaus’s version, which in its youth nevertheless displays a remarkable maturity and sense of architecture. Martha Argerich, for her part, also shows a certain exteriority in the Fantasy – something she does not do at all in the Concerto, the Toccata and the Kinderszenen. Another great pianist to remain a little outside the Fantasy is Maurizio Pollini, whose approach seems a little too hammered, struck, totally sculpted and never painted, all verticality, and which ultimately sidelines certain essential issues and tensions. The paroxysm of the hard-hitting, hammered approach to a text that becomes pain more than anything else, in a vision that is at once monolithic and often misses some of the text’s depth, can be found in Alexander Brailowsky, Igor Zhukov and Anatoly Vedernikov – though much less in the latter two than in Brailowsky.

Yves Nat’s version, however, is quite different. The pianist proposes a radical approach, perhaps even more so in the 1953 concert than in his studio version, based on articulation and sharpness, as if carved out of rock. The resulting intensity is extremely gripping, and it is precisely this commitment, in its accuracy and sincerity, that allows the more nuanced aspects of the work, such as sadness – rather than doubt here – to emerge. But commitment perhaps requires a certain height of vision if it is to remain natural. In 1943, Rudolf Firkusny offered a frenzied, highly romantic and expressive vision, while maintaining a natural rubato. The last movement is particularly taut, though sometimes a little hurried – the exact opposite of a suspended vision like those of Fiorentino or, more recently, Edna Stern, for example. With the same intention, but less profound, Andor Foldes’s version is a little smooth, not always very legible, but with a fine capacity for evocation and a constant concern for expressivity in the themes – even if this sometimes seems inconsistent. Above all, Elisso Virssaladze’s extraordinary interpretation seems to demonstrate that the naturalness of the music is to be preserved. As passionate, tense and even heart-rending as it is profound, it remains a vision rooted in sensitivity, whose intelligibility lies in its naturalness. The result is a conception of the work as a whole that demands great pianistic maturity.

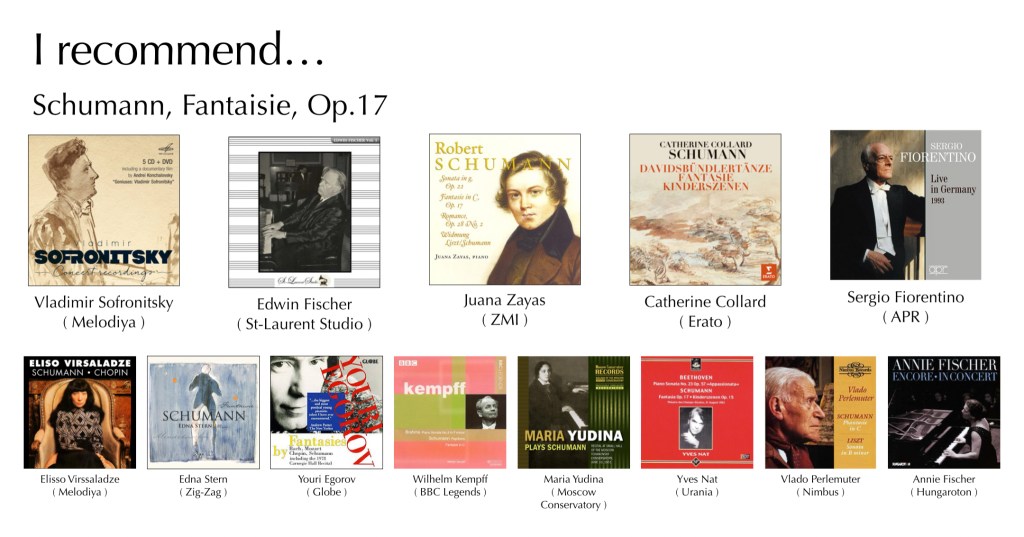

Edwin Fischer’s vision is truly exceptional, with a sense of balance that maintains intensity and tension throughout this ideal version. The sonority is simply divine, and Fischer has an unheard-of sense of breathing, giving his interpretation a breath of life, an organic dimension: this tension seems to be that of the work as it emancipates itself. It is this same sense of balance that carries Vladimir Sofronitsky’s version. However, the power of the contrasts is much more externalized, in a vision driven by the narrative, and above all by naturalness. Everything seems obvious, the interpretative choices never appear as such to the listener – in the sense that they are simply not perceived. Sofronitsky thus offers a human version, in which the height of vision, the overhang, is left in the background in favour of the emotion in its sensitive dimension, a version full of flesh, and imperfections that enter into the perfect coherence of the discourse. More recently, Juana Zayas has also offered a remarkably balanced vision that could almost be described as a synthesis of the work. It’s an interpretation at the very heart of the matter, with unprecedented sensitivity. And even when the musical flow becomes dishevelled, it seems that the pianist is seeking no control, while everything is formal perfection. It is truly an ideal that Zayas sketches out, in which romanticism flows freely. It’s liquid and fluctuating, natural in the almost landscape sense, yet human, profound, an interpretation that touches the depths of the buried soul. The imagination in each phrase is hallucinatory, a plunge into the inner unknown that lies dormant immanently, and not through external demonstration as Yudina or – above all – Sofronitsky can do – with immense success.

The sensitive, human dimension of this sense of balance is touched to the core by Yakov Flier’s deeply moving performance. But this significantly affected dimension, of the pain really felt in an emotionally contradictory setting, because the Fantaisie is also about the conflict of passions, is to be found above all in Catherine Collard’s splendid vision. The sound is sublime, the phrases are crystal clear, the passages are all highly characterised without any mannerism, and meaning is always in the foreground, as are melody and clarity – particularly in the dynamics. If we are looking for total balance, we should probably turn to Claudio Arrau, not in the studio – where he offers a version that is a little too smooth – but in public, particularly in Berlin in 1959, where his balanced conception is countered – for the better – by total commitment, which is felt in the performance. This search for the obvious, taken to its extreme by Sofronitsky, is found in the naturalness of Yuri Egorov’s version – which is not official, as the pianist was never able to record the work in the studio. Egorov plays on contrasts as well as on a clear, seamless exposition of the themes. The details are always at the service of the discourse as a whole, caught up in a vision of splendid coherence.

Sensible emotion can also take the form of sadness, even despair. This is the case with Wilhelm Kempff, who in sumptuous concerts – and not in the studio – emphasises the whole emotional dimension of the work, its pain but also its tenderness, brought out as much by the colours as by the contrasts, in a harmonic ideal towards which the whole performance seems to be heading without ever really managing to reach it: it is the story of a search. Yet Kempff attacks each phrase with determined intention, putting real fervour into his search. Vlado Perlemuter’s version is emotionally more measured, but displays a unique tenderness and passion, expressiveness and a great sense of intelligibility. The lines are as clear as the colours, and Perlemuter’s playing is extremely nuanced, while maintaining the melodic line. This concern for clarity and intelligibility of the text is echoed by Julius Katchen, in a version that is perhaps a little too controlled, and above all by Geza Anda, who shows the structure in this way, bringing the ‘skeleton’ of the Fantasy to the fore, while at the same time bringing out from within the piece itself – or so it seems – all its nuances, its sweetness as well as its nostalgia and sadness. Robert Casadesus, for his part, delivers a highly melodic interpretation, but one that lacks nuance and even comes across as rigid at times – in such an approach, Anda is clearly to be preferred. In contrast to the ‘skeletal’ approach, delicacy and subtlety find an ambassador under the fingers of Alicia de Larrocha, with a clarity that sometimes leaves room for a few staccato chords. Nevertheless, Larrocha plays the expressive registers with a certain brilliance, in an interpretation of great fluidity. The musical flow breathes a great deal, though it can sometimes be a little demonstrative – particularly in the last movement – and the pianist’s supple playing is absolutely remarkable, as is the breadth of her sound. Mitsuko Uchida’s interpretation, despite a slightly cottony sound, is also beautifully expressive, even if it is a little sequenced.

In the calmer visions of the Fantaisie, a word must first be said of Sergio Fiorentino, whose contemplation is matched only by his raw sensitivity, a form of intimacy even, in an extraordinary concert. The last movement is more of a farewell than a confrontation with oneself, and the crescendi are more like appeals than recaptures. The expressive power is truly miraculous. It is a formally sublime version, equalled only by its depth, like the more recent vision of Edna Stern, who plays in a similar register, but achieves this appeasement by other means, and a journey at human level, between contemplation, interiority, nuances, colours – all in abundance – and – a lot – of rubato, with a fine elegance – which in no way prevents the depth of the work, here very immanent, from radiating throughout the performance.

But the apparent calm, in the sense of slower tempi and less exacerbated contrasts, may also be a way of highlighting the anxieties that agitated Schumann at the time of composition – and which in truth never left him. Jorge Bolet takes this direction, sketching out a form of bitterness with extraordinary formal perfection. But formal perfection also has its faults. If you want to go too far with form, you lose meaning. This is ultimately the case in Ivo Pogorelich’s live version, an interpretation of hallucinating formal beauty – what a sound! -but which evacuates all the tragic and human dimension in favour of a form of complacency in pure sound. Worse still, Evgeny Kissin delivers a performance that is certainly extraordinarily refined, but he loses himself a little in the detail, with a few mannerisms that affect the discourse. But the biggest disappointment comes when listening to Grigory Sokolov, who loses the melodic line in detail that becomes anecdotal. The touch is hard, the piano even seems brittle. Here the pianist seems to fall back into some of his characteristic excesses. The extreme, unsustained slowness loses its tension, particularly in the unlikely silences. At the end of the day, all that comes across is manner, even affected pretension, to a meaning from which we are moving further and further away – a far cry from the genius of the first Naïve recordings.

But bringing the Apollonian dimension of the Fantaisie to the fore does not necessarily go hand in hand with appeasement. It can also refer to a form of refinement, of finesse in declamation. Nor does it mean smoothing out all the contrasts. Benno Moiseiwitsch, for example, in a late recording, offers a vision that is very clear, but also very refined, preserving darkness and nostalgia rather than inner peace. Walter Gieseking, for his part, preserves the tragic dimension, the sense of loss, while not foregrounding exacerbated contrasts. The formal concern is thus preserved, while maintaining the tension in the text. And then there’s the search for another kind of balance, a formal one at that, to bring to the fore the immanence of the text’s internal tensions, through interiority rather than exteriority. This is what Clifford Curzon does, on Decca, and with even greater dimensions in a splendid live version – on Orfeo. More recently, Francesco Piemontesi has also demonstrated great poetry, in a resolutely Apollonian version. Stephen Hough was also a poet – on Erato, in 1989 – with an interpretation full of imagination, teeming with ideas, in a highly narrative profusion. Although sometimes dark in atmosphere, the sound remains highly coloured, with a very exacerbated rubato – one almost gets the impression that Hough is trying to avoid repetition at all costs. In 1986, Murray Perahia also gave a live performance of great delicacy and light, highlighting the contrasts in a remarkably legible discourse.

From this point of view, the distinction between interiority and exteriority is undoubtedly relevant in distinguishing certain approaches. Vladimir Horowitz’s vision, in 1965 for his grand return to Carnegie Hall, takes us completely in the opposite direction to his interpretations of the Kindersznen, in that it brings us resolutely back to the exterior – and undoubtedly remains too external to the work. The last movement would almost seem to be a demonstration – formal but also technical – the 1968 Kreisleriana are, in my opinion, much better. So the question is, can we reconcile exteriority and interiority in expression? Nelson Freire achieves this very well, and there is no doubt that the great contemporary versions possess this perspective – even if the mix is sometimes too heterogeneous, as with Arcadi Volodos, who in 2022 offered a version whose gigantism, absolutely dizzying, bordered on excess, despite its incredible depth. Alfred Brendel, too, plays on balance, in the same Apollonian logic that underlies all his interpretations, with a full sonority, roundness in the attacks, and tenderness, nostalgia, in very natural phrases, with very little rubato. Leif Ove Andsnes delivers a shady but very balanced version. Andsnes always puts naturalness first, which really does the work justice: it’s as if the text speaks for itself, without being neutral or stale. Marilyn Frascone’s vision is also in this pared-down style, despite a real sense of rubato and a little too much affect – though it’s still a version full of beautiful moments. But formal perfection is no guarantee of soul. Éric Le Sage’s version, which is much more recent, is certainly a great success formally, but it remains a little restrained, even though it is beautifully legible. But sometimes, on the contrary, the soul arrives with a deep and total commitment. With Shura Cherchassky, for example, even though there are a lot of wrong notes, they do not detract from the authenticity of the discourse.

To conclude, I leave you with a selective discography. Five reference versions, each with a singular perspective, and eight others to be approached with a better knowledge of the work, as they open up more in-depth perspectives.

Laisser un commentaire