The original podcast (narration in French, English and German subtitles)

A little over a year ago, in June 2023, I took part in a series of short programmes on the Wilhelm Furtwangler Society’s YouTube channel called ‘The recording that made an impression on me’. I chose to present the legendary recording of Brahms’s 3rd Symphony, captured live in 1949 and published by Audite. I was keen to present a recording of Furtwangler conducting Brahms, because I think that, along with Bruckner and Wagner, this is the greatest osmosis that has ever existed between Furtwangler and a composer, even more so for me than with Beethoven, with whom Furtwangler has so often been associated. For me, this is the most beautiful osmosis, for reasons that are in reality both ‘purely’ artistic – even if there is no such thing as purely artistic – and material. The material reason is in fact very simple, almost prosaic: the orchestra and above all Furtwangler’s post-romantic conducting style were in a way made for Brahms. The reason, which is a little more independently artistic – at least in terms of the material conditions of the performances we’re talking about – is that Furtwangler’s conducting, with its sense of organicity and its ability to convey both transitions and themes with great expressivity, is undoubtedly the one that suits Brahms’s symphonic works best. And I think this all the more because the conductors I personally admire most in Brahms are often Furtwangler’s heirs – Carlos Kleiber, Karajan, Eugen Jochum, or more recently Herbert Blomstedt and his complete works available on Pentatone.

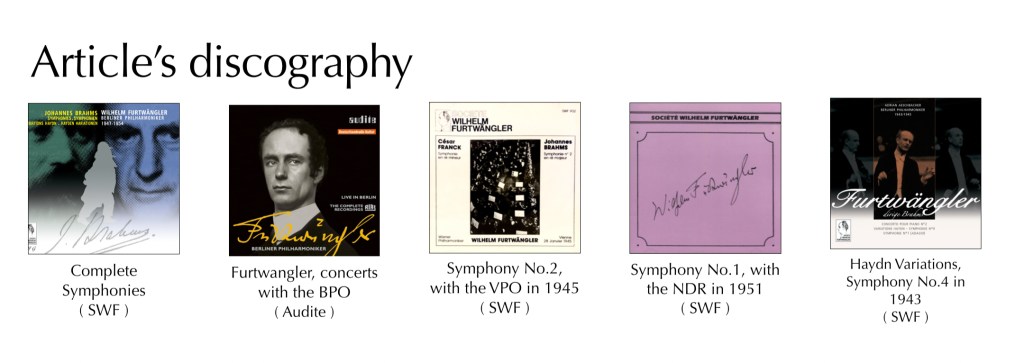

Having said that, perhaps a word should be said about the various recordings we have of Brahms’ symphonies by Furtwangler – although I’m not going to talk about the Haydn variations, which are treated rather like symphonies, that’s why, and I’m leaving out the performances of the Hungarian Dances, the first and third.

First, let’s talk about the First Symphony. First, there’s the 1947 Vienna version. This is the most ‘official’ version, published by EMI. But it’s also the most fixed, the most static, while at the same time being very little rooted in the orchestral material, which paradoxically gives it a kind of heaviness. I think we can leave it in the background compared to the two recordings from 1951 in Hamburg and 1953 in Berlin. In 1951, we are dealing with one of the greatest Brahms recordings of the twentieth century, in a superb sound recording by Friedrich Schnapp, and in 1953, we have an interpretation that is perhaps a little more lofty, but with real commitment and quite absolute orchestral mastery. I think it’s fair to say that this is the symphony in which Furtwangler had the greatest influence on the conductors who followed him, starting with Karajan, who returned to Furtwangler a great deal, notably in 1949 in Vienna and in 1988 in London.

The fact that Furtwangler was particularly successful with the First Symphony is actually easy to understand. It’s a work that implies a certain weight, great orchestral substance, mass and above all great strength. And then there’s one of the most ‘metaphysical’ passages in the history of the orchestra, in the introduction to the last movement, which really does seem to come straight out of nowhere, particularly in the arrival of the trombone.

We have a huge number of great live recordings of Furt in the first symphony, in Italy, in Amsterdam of course, and then all the versions with the Berlin Philharmonic. Then comes the Second Symphony, which is a bit like Brahms’s ‘pastoral’. But Furtwängler didn’t consider it as such at all. For him, it’s all about contrasts, forces that once again clash, apparent contradictions even in the narrative, and the coherence comes from an absolutely extraordinary sense of narrative. The discourse is very lyrical, and above all we get the impression that Furtwangler is going as deeply as possible into a very raw form of material. We are not at all in the much more Apollonian and even calmer vein of a Bernard Haitink, or even a Celibidache.

Furtwangler’s great recordings of the Second Symphony are, of course, 1945 in Vienna, a recording that stands completely apart in the discography – some would almost regard it as irrelevant, so immersed is Furtwangler in the tragic intensity – and then 1948 in London, a recording that is a little more rigid, more formal, and in fact smoother, and finally the sumptuous 1952 concert in Munich, in which the balance is absolutely sovereign.

In the third symphony, by contrast, we return to what we found in the first. Once again we have a work with two very stormy movements framing two central movements that are calmer, at least in appearance. The central movements of the Third undoubtedly require a more immediate apprehension, less metaphysical, more luminous, or at any rate more rooted in what is happening in the present moment. We have two immense recordings of this symphony by Furtwangler, each in its own way, because they are extremely different. On the one hand, we have the turbulent, stormy interpretation from 1949, a masterpiece of contrasts, and for me the finest synthesis of Furtwangler’s work in Brahms’s music. Then, on the other hand, there’s the much more contemplative and, quite simply, much slower 1954 performance, which testifies to a height of vision and artistic maturity that are truly astonishing.

And then, finally, the Fourth Symphony. It’s a much more complete work in a sense than the others, more modern too, offering a journey between moments of unique tension and very contemplative moments, in movements that regularly oscillate between one and the other without ever seeming incoherent. Finally, there is Brahms’s Fourth Symphony. And Furtwangler leans towards tension, in a way reducing contemplation to a transition between themes that are both tense and tragic. Basically, while this is a dramatic symphony, in the sense that there is almost something theatrical about Brahms’s Fourth, Furtwangler’s vision is much more metaphysical, eschewing all dancing in favour of lyricism alone, and going almost as far as the race to the abyss. There are several versions of the work by Furtwangler, and they are all similar in the sense that, although they do not necessarily have the same intensity, they are all driven by the same logic. First there’s the 1943 version, which is fairly extreme in its intensity, then the much more tragic 1948 version, which is more about renunciation, albeit with a certain violence, than despair, and then the last remarkable version is, I think, the 1949 version, in Wiesbaden, which is an excellent synthesis of Furtwangler’s vision of this symphony – it’s also the one that the SWF is releasing in the box set ‘Furtwangler conducts Brahms’.

And now that we have sketched out a brief tour of the recordings of Furtwangler conducting Brahms, I propose that we try to identify certain cardinal points of the specificity of Furtwangler’s art in the music of Brahms.

The first thing that springs to mind when describing the way in which Furtwangler conducts Brahms is all the power that emanates from it. I don’t know if it’s something that could be attributed to the composer, but the force of Furtwangler’s Brahms strikes me as even more powerful than that of his Beethoven. Furtwangler’s Beethoven is not fundamentally modelled, constructed, traversed from one end to the other by a force that transcends him; on the contrary, his Beethoven is resolutely human, and even, beyond humanity, genuinely idealistic, whereas his Brahms is modelled and traversed by a ‘transcendent’ force – a word that should not be taken with too many implications either – a force that transcends him and encompasses him while carrying him along. It is this force that Furtwangler will nuance in very different forms – the possibilities are infinite – in Brahms’s first symphony.

The second point I’d like to address is what might be called organicity. Furtwangler’s music is systematically organic, and in the context of Brahms there are two manifestations of this that can be linked. Firstly, it is ethereal, but secondly, it is always breathing.

While Furtwangler’s Brahms is imbued with great strength, it is not heavy, and is perhaps even more ethereal than his Beethoven. There is a way of linking phrases, and in a sense almost painting phrases, in Furtwangler’s Brahms: the conductor seems to melt a landscape rather than sculpt it.

In the first movement of the Second Symphony, for example, in 1945 with the Vienna Philharmonic – it was the last concert Furtwangler gave during the war before he had to flee to Switzerland – the chords literally seem to fly, in a kind of general haze, of course – and this is perhaps also linked to the recording – but with remarkable clarity – which, as always with Furtwangler, lets the shadows show through, and in fact allows them to emerge. Contrasts thus seem to be marked more by atmosphere than by dry attacks.

The vision of Furtwangler as a conductor who favoured slow tempi has regularly been maintained, but this is obviously absolutely false, and this is my third point. It’s also interesting to remember that Furtwangler conducted Parsifal in less than four hours, whereas Toscanini, who is often portrayed as a fast and lively conductor, conducted the slowest in history. With that aside, the main thing to say about Furtwangler’s tempi is that they varied enormously, even within the same work, and even within a single movement, if not from one moment to the next!

Furtwangler was capable of maintaining some of the fastest tempi in the entire history of interpretation, but what is striking – or rather striking to the ear! – was the natural way in which he alternated between different tempi within the same movement, and above all the way in which he let the orchestral fabric breathe.

In the last movement of Brahms’s Fourth, again in 1945 with the Vienna Philharmonic, Furtwangler proposed perhaps the fastest tempo in history, and yet the music still lives, precisely because it breathes. Breathing is even the necessary condition for sustaining such a tempo.

Perhaps Furtwangler’s conducting seems in a sense more natural to the music of Brahms than to that of Beethoven or Mozart. Perhaps it is even the most beautiful osmosis between Furtwangler and a composer, in the same way as with Bruckner or Wagner. One of the reasons for this observation is that, whereas orchestration changed a great deal in the Classical or early Romantic period, Brahms’ orchestration dates from the late nineteenth century, and perhaps Furtwangler’s post-romantic orchestras are more in keeping with a more historical approach, with what the composer really had in mind. Having said that, it’s essential to keep the ‘maybe’ in the discourse because, let’s never forget, we don’t know what was going on in the composers’ little grey cells.

Nevertheless, there is a major difference between Furtwangler’s conducting and that of the other great conductors specialising in Brahms’s music. I propose to make a comparison: on the one hand Furtwangler, and on the other two of the greatest interpreters of Brahms in the second half of the twentieth century, Carlos Kleiber and Evgeny Mravinsky.

What we notice in the first two cases is that we are dealing with finely chiselled interpretations. Brahms’s symphonic music has a great relief, a music that seems to call for sculpture more than painting. Yet Furtwangler ties the phrases together and seems to stretch the music horizontally as well as vertically, whereas the two previous interpretations seem to stretch vertically first.

Furtwangler’s Brahms is bound together with true lyricism. Its expressiveness is embodied in the phrase, which takes on a relief in its entirety, in its unity. Here, the music is shaped by the unity of the work, and coherence comes from the whole. There is a perpetual evolution here, almost a permanent transition.

Where Kleiber and Mravinsky let the listener guess where they wanted their interpretation to take them, Furtwangler’s interpretation, with its expressive, lyrical brushstrokes, allows the listener to really go into the unknown. Of course Furtwangler knows where he’s going – even if his interpretation often depended on the moment, always varying from one evening to the next, for example – but the listener doesn’t, because the music seems to be created in front of him. Furtwangler always remembered that interpretation had to be conceived in terms of its effect on the listener, that what mattered was what the listener perceived – hence the great differences, really major differences, in the same works between Furtwangler’s live recordings and his studio recordings. This linking of the interpretation primarily to the audience’s perception obviously helps to develop the whole tragic dimension of Brahms’s music, what might almost be called the violence of uncertainty, which is particularly evident in the finale of the Fourth Symphony, for example in a live performance in Wiesbaden in 1949.

Laisser un commentaire