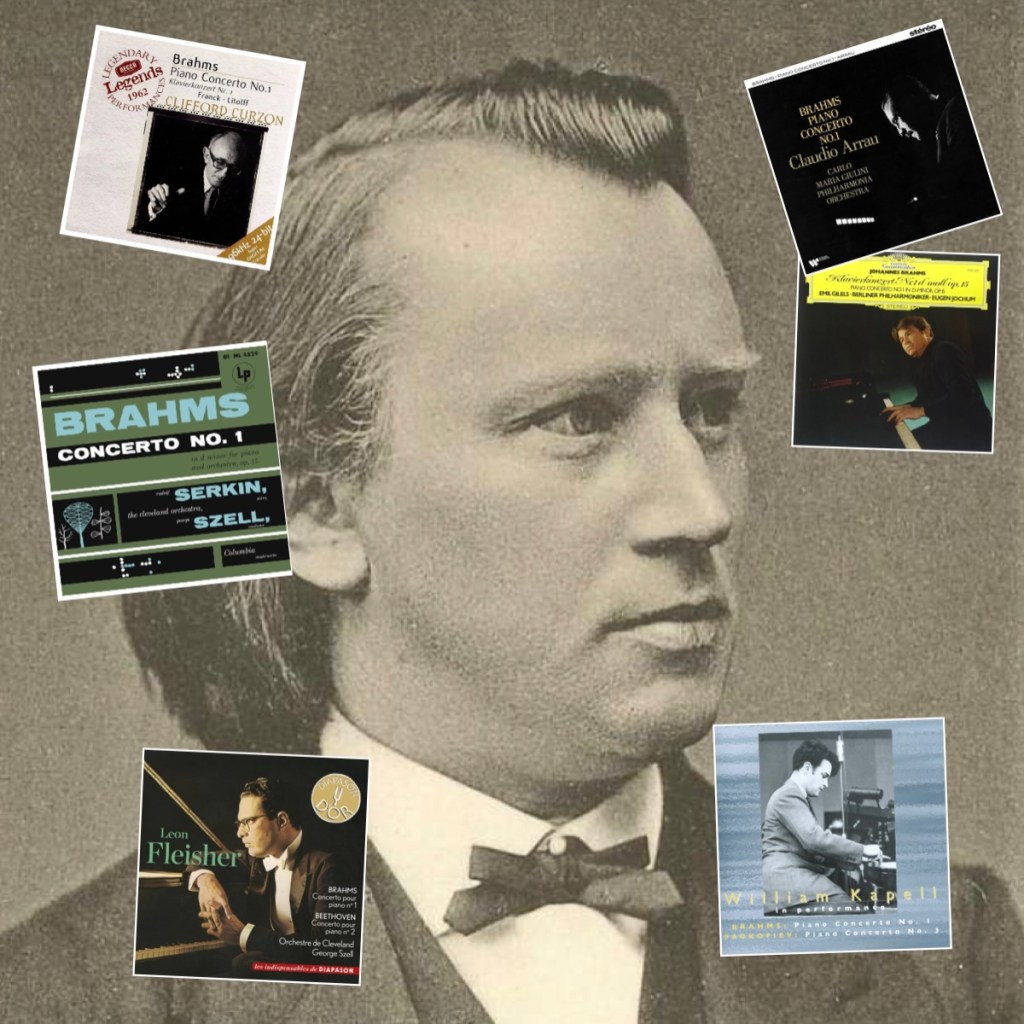

When preparing a blind listening session, there is always the question of which versions to choose. In the case of Brahms’s First Piano Concerto, there is no shortage of versions. I have chosen not to select the really old versions, recorded on 78 rpm. It’s not that they don’t have a place in the selection – as long as you know how to distinguish between the sound recordings, which are often good, and the surface noise – but rather that when I listened to them again I didn’t find that any of them sounded better than the five versions I wanted to keep. Some, however, are very good, like the excellent interpretation by Artur Schnabel and George Szell, or, live, by Vladimir Horowitz with Bruno Walter – or even Arturo Toscanini. Others are less so, like that of Wilhelm Backhaus, conducted by Karl Böhm. What this points to as a problem is the role of the conductor. Brahms’s First Concerto demands an equal relationship between pianist and conductor, each of whom has a fundamental role to play in the performance of a complex and demanding score – regularly dissonant, extremely innovative for its time, even though it is a work from the composer’s youth. One of the first milestones that absolutely had to be kept in the selection, it seems to me, was Claudio Arrau. I preferred the version with Carlo Maria Giulini, with its more even relationship with the conductor, to the one with Bernard Haitink, more refined at the piano but also more restrained with the orchestra, and to the live version with Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt, more subject to certain hazards, just like the one with Rafael Kubelik – not to mention the one with Igor Markevitch, much less interesting. I also liked the version by Emil Gilels, conducted by Eugen Jochum, a real reference, available from DGG. George Szell is undoubtedly the benchmark conductor for this work, in which his rigour provides an ideal setting for the piano, underlining the dynamics and letting the score express itself. I have therefore chosen three versions conducted by Szell, those of Clifford Curzon, for many the absolute reference when it comes to this work – more so than the affection that runs through him when he is accompanied by Eduard van Beinum, despite the moving and superlative performance of the Concertgebouw Orchestra -, of Rudolf Serkin – whose studio I chose, as I was not familiar with the 1968 live version, also with Szell, and not the version with Munch, at the time of this listening, what a mistake! -And lastly, Leon Fleisher, whose discography we should be talking about more, because although it is small, mainly because of the paralysis that affected him for most of his career, it is extraordinarily homogeneous, in all the repertoire he has worked on. I left out Wilhelm Backhaus in the 1950s, again because of Böhm’s conducting – inconsistent, lacking coherence and above all tension, which is crucial if the dramaturgy, in the sense of the theatricality of the work, is to be expressed – and then Richter-Haasser – live, with Kurt Sanderling -, but only because I only wanted five, and studios allow more blind listening – because of the sound recording, which is why I didn’t choose William Kapell’s extraordinary version, with Dimitri Mitropoulos in New York, a masterpiece of expressiveness and drama. Gould’s version, with Bernstein, struck me as too particular and relatively incomparable, in the truest sense of the word, which is why I discarded it too – but it’s an experiment that’s well worth listening to, and for its aesthetic qualities, to the extent that it influenced Bernstein to the point of making him impose the same incredibly slow tempi on Krystian Zimmermann, years later. Some versions, I find, lack texture, such as those by Arthur Rubinstein – with Fritz Reiner – or Maurizio Pollini – with Claudio Abbado. I immensely regret that Edwin Fischer never left us a record of this concerto, it really seemed made for him – but if you don’t know them, go and listen to the recordings he left us of the second concerto, with Furtwangler in particular, which are truly monumental. Many more confidential live versions exist, and deserve to be discovered, such as Solomon, with Rafael Kubelik, but also with Eugen Jochum, or of course the exceptional version by Wilhelm Backhaus with Pierre Monteux, who also conducted it with Fleisher, or John Ogdon, conducted by Leopold Stokowski – and an overflowing imagination.

Arrau’s version, somewhat hampered by the 1961 EMI recording, suffers from certain slowness. It’s not so much heavy because of the weight of the orchestra or the pianist’s touch, but rather because of the accentuation and rubato, very pronounced in a general slowness. I should have chosen Haitink after all! There is even a slight loss of tension in this vision, as if the piano were in constant suspension and couldn’t really find its place. It’s rather disappointing, but it’s still a superb version nonetheless! Added to this is the fact that blind listening, in extracts, inevitably deserts versions that require, notably through their slowness, a longer duration, and thus a more contemplative listening attitude. The first movement thus appears somewhat jerky and choppy, while the second is absolutely fabulous in its expressive power. Gilels and Jochum’s vision, which is also rather slow, suffers from a number of mannerisms that detract from the remarkable naturalness of the whole. The height of vision here is quite impressive, in a work that actually seems rather cathedral-like. The remarkable formal beauty, especially in the second movement, should also be emphasised. From this point of view, the first movement is again rather choppy, and suffers from some of the same faults as Arrau’s version, which this time lie in variations in tempo: where there was too much structure, too much construction in Giulini’s version, this time the naturalness is prevented – in part, this is a very fine version on the whole – by a lack of structure, in the sense that each phrase tries to be expressive, but the whole lacks a link, a body – certain phrases seeming independent of one another. On the other hand, here we have a monumental first movement, playing on the feeling of crushing, which at the same time benefits from great flexibility in the expression of the phrases.

George Szell is more on the metronomic side. His relentlessly rigorous conducting paradoxically allows the phrases to be more expressive, with the melody and balance truly magnified. Leon Fleisher’s interpretation follows this path of sovereign balance, with rare nobility and elegance. This is a version of extraordinary formal beauty, with no mannerisms or eccentricities, but carried by an absolutely sovereign sense of architecture, construction, naturalness and rhythm. The flaw lies more precisely in the metronomic character, with a touch of rigidity at times, in tempi that are on the whole very brisk – which suffer in comparison. Rudolf Serkin shares this form of stiffness, without being deadened by it. It is above all his sound and his maturity – in the sense of his height of vision, his overall conception – that make this version a true benchmark. George Szell is led by Serkin into the same defects, in this case rigidity, while maintaining a relentlessly rigorous accompaniment, which at the same time provides a splendid and ideal setting for Serkin’s piano. But the most extraordinary of the listening versions remains without doubt that of Curzon. The finesse of the phrases is extraordinary, the relief is sculpted while being carried by a sonority rich in a thousand nuances and colours, the balance serves the narrative while underlining each atmosphere, each climate that runs through a work whose complexity is revealed. George Szell is driven by this ideal, finding a hallucinating formal perfection and an extraordinarily moving truth. He introduces just the right amount of tension, relief and heroism, as well as tenderness and nostalgia, in the first movement, but it is above all in the second that he proves himself capable of an unequalled power of evocation, with a restraint that makes it the most touching interpretation of all – at least for me. Curzon’s elegance lies not only in this restraint, but also in an authenticity and sincerity in the face of the text that is almost a revelation.

So what can we learn from this panorama? First of all, of the versions selected in the blind listening session, Curzon stands out quite clearly, ahead of Serkin and Fleisher, also accompanied by Szell. Gilels and sueront Arrau undoubtedly lost out in the comparison, due to their different temporality, which requires listening over a long period of time, and an appreciation of the work for its own sake that the format prevents – this is, moreover, its limitation, which must be clearly identified and named. As for the versions not selected for this exercise, I recommend above all Backhaus and Monteux – watch out for the sound recording -, Kapell and Mitropoulos – a masterpiece, really -, Serkin with Szell – much better than the studio recording – and then Gould and Bernstein – for the experience. The others are well worth listening to, and enjoying, of course!

Laisser un commentaire