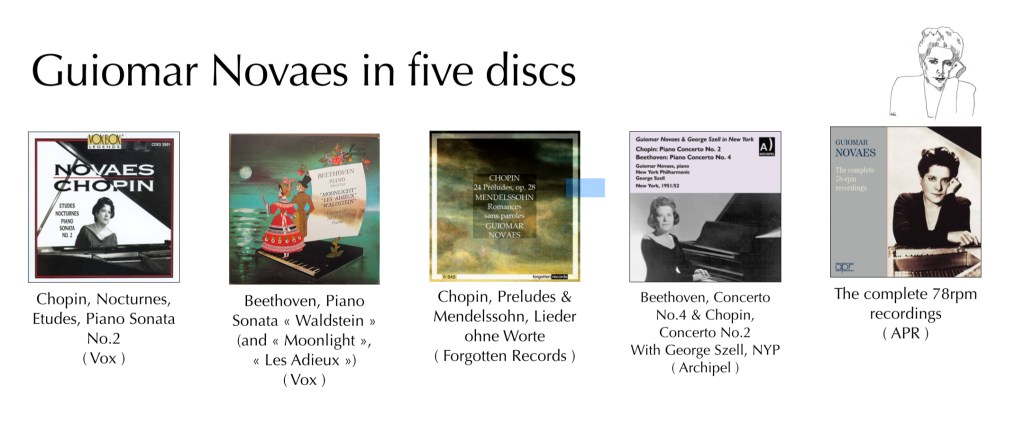

Guiomar Novaes (1895-1972) was an incarnation of the most absolute Romantic pianism, between possession and tenderness, caught up in emotional tensions that were at once incandescent and uncertain, at once fragile and determined. While Novaes’ discographic legacy is – unfairly and far too meagre – it remains an important sum devoted to the music of Chopin, even if the sound quality – perhaps the recording, but it is certain that the Vox reports do not help at all – sometimes detracts from it. The Nocturnes, Etudes and Preludes are complete, and there are some scattered pieces: Ballade No.4, Polonaise Op.53, Fantaisie… A treasure trove of which I have never tired and of which I hear too little, even though each of these recordings could be considered an absolute reference! So this is my chance to introduce you to this collection, with sound extracts to back it up.

Novaes’ Chopin is neither salon music nor music of the mind. This is a Chopin caught up in physicality, materiality, rooted in the organic. This is what gives it its incarnation, its vitality, this very strong characterisation, carried by a very pronounced rubato and by an alternation between different vertigoes. Listening to Guiomar Novaes play Chopin makes you feel overwhelmed. And yet you don’t feel overwhelmed by a force that overwhelms or overturns, because each note draws its force from within, it’s an immanent force that seems to come from below: it’s not the sky that’s falling, it’s the earth that’s shaking! But if we can perceive generalities, and a certain idea of Chopin’s music, Novaes also identifies different tensions in different works, which makes these recordings an extraordinary and unique sum in the discography, a sum that is nonetheless sometimes overlooked or underestimated.

Of course, Novaes’ virtuosity is phenomenal, but it is always at the service of depicting feeling. First of all, there is a narrative logic: it’s not so much evocation, in the sense that it’s not diffuse, as adventures filled with great gravity. The original contrasts in the score are all emphasised, while the variations in atmosphere and rubato add to the highly exacerbated romanticism of Novaes’s style. Yet each piece is considered in its own particular way, so that the emotional stakes seem highly focused and indeed much higher. There is no general logic, apart from a few regularly recurring features, and each piece is magnified in its singularity.

This gesture of particularisation, of characterising the pieces, is obviously most noticeable in the recording of the etudes. What is most surprising about the Études par Novaes is that, despite the great diversity that gives each piece its unique character, its typicity, there is nevertheless a remarkable unity that emerges from the whole, or at least an extraordinary continuity, a coherent path.

Novaes’ Chopin has a physical impact on the listener, it ‘concusses’ him, makes him dizzy, and it is a real vertigo that takes hold of the listener and seems to surround him. And this ‘concussion’ also involves a privileged representation of torment, sadness and the feeling of loss. There is a much greater sense of the past, of the memory or illusion of memory of something lost and impossible to find again. This concussion comes through a kind of halo of sonority, through the breadth and power of the bass that surrounds us to finish provoking this vertigo.

And yet, even though Chopin seems to be in pain most of the time here, he continues to sing all the time. There is an extraordinary lyricism in Guiomar Novaes’ recordings, and the drama and theatricality are magnified by this way of never giving up singing, of always continuing in this singing that manages – almost miraculously – to link different elements that in reality only interact and weave ever more links with each other.

This material, physical, earthy gravity, in a sense tangible, which immediately becomes part of the moment and seems to be engraved against a wall, is to be found in Novaes’s interpretation of Nocturne Op.48 No.1. Although the melodic line is always singing, it regularly changes into cries and appeals, making for an absolutely heart-rending performance.

This is Chopin in the moment, not in meditation or weightlessness – as with Nelson Freire or Claudio Arrau, for example. All the issues at stake seem concentrated, brought together in a very particular form of tension. Listening to these recordings is not a matter of anticipation; it concentrates the tension and makes a direct impact, one that is certainly not watered down. In this respect, it’s almost nerve-wracking to be brought back so directly – but not brutally, precisely because it’s so natural – to the temporality of the present moment, of the instant without really understanding, because it’s above all intuitive, almost instinctive. Novaes’ playing is not that of a static piano, suggesting and leaving the listener to make the links, it is that of a moment that must always be the most important, and seems more important than the one that precedes it.

As a result, the listener finds himself physically and emotionally marked – and what if it’s much more linked than we’d like to believe? – by Novaes’ interpretations, and this body of work has long deserved a remastered edition – something we’ve been waiting for in vain for far too long. In the meantime, I highly recommend the Forgotten Records editions, especially the Preludes Op.28 – along with Mendelssohn’s Romances sans paroles, for me the greatest piano disc devoted to Mendelssohn.

Laisser un commentaire