Clara Haskil is an artist who is not to be missed. She is one of those personalities who have left their mark on the history of performance and who have had a considerable impact on the pianists who have followed them. Haskil was a highly inspired pianist from an early age: as a child prodigy she was taught by Richard Robert, who had been the teacher of a certain Rudolf Serkin in Vienna, before becoming a pupil of the great Alfred Cortot in 1907.

Haskil was a great virtuoso in her youth, but there are no recordings from this period – except for Schumann’s fabulous Abegg Variations in 1938. Indeed, due to severe scoliosis, we can only listen to the records she made after the war, and this is what has led to the claim that Clara Haskil’s playing was too far ahead of its time: indeed, the late style we know of is sober, clear and without any excess, as the scoliosis physically diminished the performer. But the Apollonian and very luminous aspects of this late playing give it a timelessness that is rare in the history of interpretation, so much so that one could very well ask the question: « Who doesn’t like Clara Haskil? » to a gathering of music lovers and get no answer. Clara Haskil’s music is full of vitality, and it is perhaps this aspect that is most striking. This music contains within it a kind of organic mystery, something indiscernible that seems to unify all the other characteristics of Clara Haskil’s playing. This vitality is embodied in the moment, the music seems to be in full evolution, in full metamorphosis, and Clara Haskil’s phrasing gives the impression of being systematically suspended, floating without the tension disappearing and the musical flow stopping, the music never dying. This lively aspect of Haskil’s music is particularly noticeable in his performance of Mozart’s twentieth concerto. There is a great strength that emerges, as well as a permanent, organic evolution: there is a kind of flow similar to the development of a thought, without it seeming forced or excessive at any point: it is, in the end, the interpretation that seems most natural of the work, at least for me. Haskil’s own vitality makes his interpretations extremely luminous, in a sense we could almost say that it is a sunlight – without being absolute, there are always a great number of nuances in Haskil. The dynamics are the embodiment of all of Clara Haskil’s seemingly natural reflection. Thus the bass is very clear, quite easy to discern, but far from taking up all the space, the treble is detailed and everything seems to be imbued with the life of the composition, everything seems to be at the service of the musical flow. Haskil’s dynamics are at the service of Scarlatti’s vivacity. Indeed, even if the Sonata K.87 seems slow, it is extremely luminous, illuminated by several flashes of light that the performer brings in at the moment she wishes. In this respect, if it is not a performance of dazzling technical virtuosity – Haskil after the war could probably no longer afford it – the depth that emanates from it makes the music unbelievably profound, like a dialogue of questions and answers always brought to life in an extraordinary coherence.

The colours in Clara Haskil’s style are often quite clear, almost pastel in Mozart’s music, more nuanced in the romantic repertoire. However, they never appear saturated, they are rich without ever forcing the line. Even if these colours are rather pastel or at least rich in their nuanced character – and therefore not saturated – the music is never mawkish in Haskil. Clara Haskil’s virtuosity, which the critics speak of at the beginning of her career, is set in a humility and sobriety to put herself in her most famous recordings of the composition in the logic of simply underlining what the work shows of itself. All the colours in Clara Haskil’s playing allow her to adapt to the particular climate that the composition requires. In the Traumerei des Kinderszenen, Haskil offers rich but very restrained colours, which allow her not to accentuate the already nostalgic side of the piece, and above all to nuance each bar. Haskil’s playing is deeply imbued with great strength. It seems immense, and perhaps this semblance of infinity lies in the pianist’s ability to illuminate the composition with great verticality. Haskil uses fast tempi, often quite fast, to emphasise the clarity of her vision of the works. The only horizontality to be found in Haskil’s work is the ability to stretch the phrases from time to time, but without ever becoming too mannered. This strength becomes particularly enormous in the Beethoven interpretations. Haskil develops a power of sound that is not always usual for him, and he combines this power with all his colours to bring out all the clarity of the « Tempest’s » resolute purpose. It is a storm that seems to be both full of inexhaustible breath and permanent movement.

Clara Haskil generally directs her interpretations towards something bright and, in a sense, positive, reconciling or harmonic (in an almost philosophical sense), but sometimes there remains what takes the appearance of a certain darkness. Nevertheless, this darker aspect most often takes the form of something akin to a struggle, with a goal and an objective towards which the piece seems to be striving. Also, the good always seems to prevail in Haskil. The sonata D.845, when Haskil is playing, has this hint of darkness, like a momentary violence, held back at certain moments, so that the pianist can hammer with great force, striking out like a rain of blows, almost warlike and above all very offensive. But what stands out at the end is that Haskil always puts her colours, once again very clear, at the service of her subject, adding coherence to the climate that seems to have been set by Schubert himself. Even if there is some darkness, it is most often present in the form of a very slight nostalgia, which shines through here and there. Indeed, it is the gentleness and calmness that probably characterises Clara Haskil’s style the most. Yet the performer always seeks to interrogate the pieces with depth, and in addition to the climate that inhabits each of her interpretations, Haskil offers a coherent logic, in which she can become an extremely narrative pianist. Perhaps the composer who most reveals the narrative that Haskil can demonstrate is Mozart. In the Tenth Piano Sonata, Haskil reconciles the hint of nostalgia in each phrase with the whole sweetness and delicacy of the piece, and so each change of mood becomes coherent, as natural as if a demonstration – a very fine one, for Haskil’s playing is not demonstrative in the arrogant sense of the word – were to make the truth obvious.

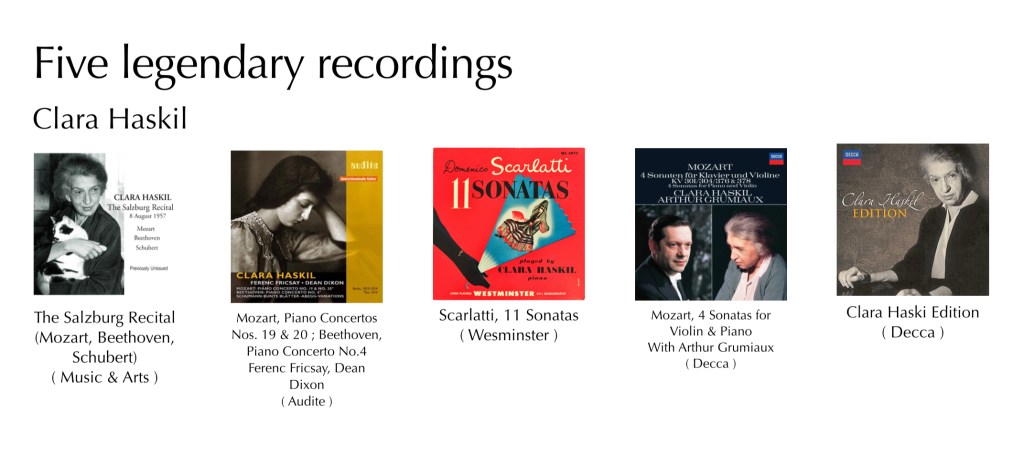

Clara Haskil unfortunately died relatively young, at the age of 65, following a fall down a flight of stairs in 1960. She was a complete pianist with a distinctive style whose originality lay in her humility and timelessness – at least according to the recordings we know of her. She remains to this day a piano legend, a role model for the generations of pianists who listened to her and were inspired by her, and many of her recordings are regarded by many critics as absolute references, such as her Mozart concertos with Ferenc Fricsay, her second Chopin with Igor Markevitch, her collaboration with the violinist Arthur Grumiaux or her Schumann solo recordings.

Laisser un commentaire