Mozart’s symphonies seem to be imbued with a certain idea of perfection, a quest for intelligibility. There’s no denying that these are works with a certain physical impact – and it’s no coincidence that Mozart’s harmonies even have beneficial effects on plants, and are even used in New Zealand to cradle the vines. So how does Mozart’s music, which from the outset seems so physically attached, manage to speak to the mind, and how do conductors go about conveying this? First of all, Mozart’s music is fundamentally intuitive. There are no prerequisites for appreciating Mozart, and he is one of the most popular composers today – and not just today. For the performer, therefore, it is the obvious that needs to be emphasised, without adding superfluous elements that would add unnecessary complexity and ultimately detract from the coherence of the discourse.

For a long time, Mozart’s symphonies have been heard with large orchestras, with a broad, full sound, silky strings and soft woodwinds. However, the most famous interpretations – or rather the most widespread aesthetic in the field – are in reality quite far from what Mozart’s idea might have been. Indeed, while we can never be inside the heads of composers of the past – that said, nor can we be inside the heads of those of the present – there are things that would have been impossible for them to have imagined. So today’s performers have a certain amount of leeway as to what might hypothetically have been the composer’s intention.

The most successful versions on period instruments are most often those that manage to combine the legibility of the different sound levels, the relative dryness of the attacks and the roundness, the very warm and even happy side of the sonorities. The orchestra as a whole can sound gilded and teeming, as with Frans Bruggen, who adds to these colours and details a concern for construction and architecture. A great admirer of Furtwangler, Bruggen takes extraordinary care with transitions, both in their preparation and execution, while preserving the originality of each theme. The atmospheres are superimposed and follow one another in an extremely coherent way, while retaining the complexity of Mozart’s symphonies. But Bruggen adds what makes him unique in the world of performance on period instruments: that form of metaphysics, of almost mystical spirituality that transcends each of his interpretations. This is clearly evident in his reading of the introduction to the 39th symphony, with this passage as if in suspension, floating but nonetheless taut enough to ensure that the line is never lost.

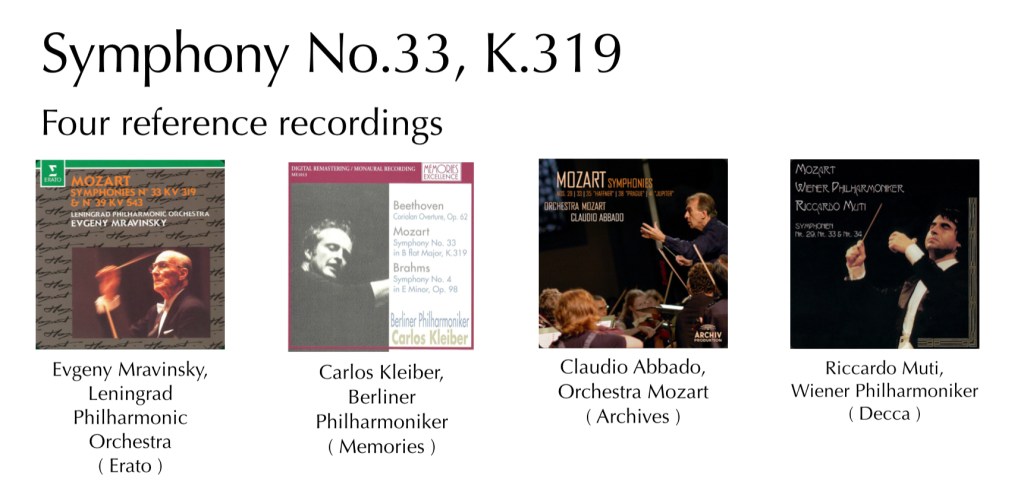

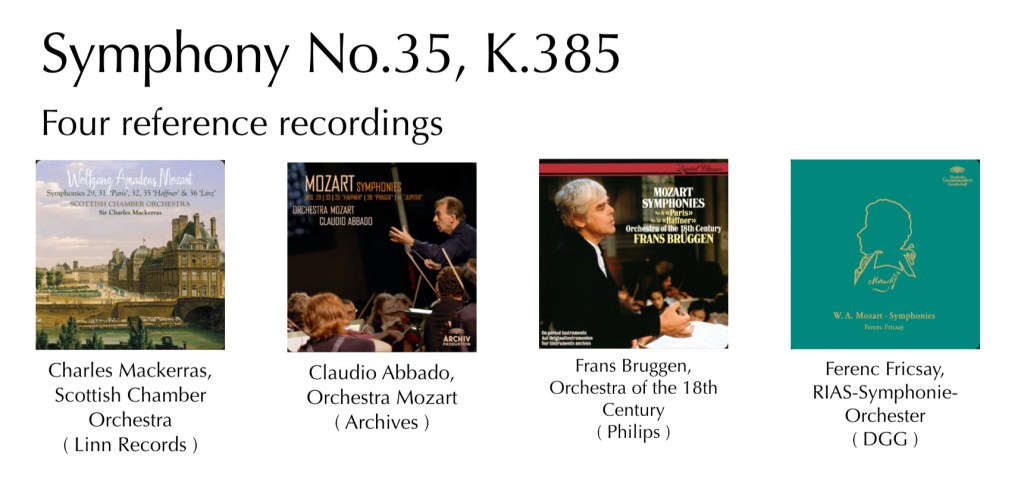

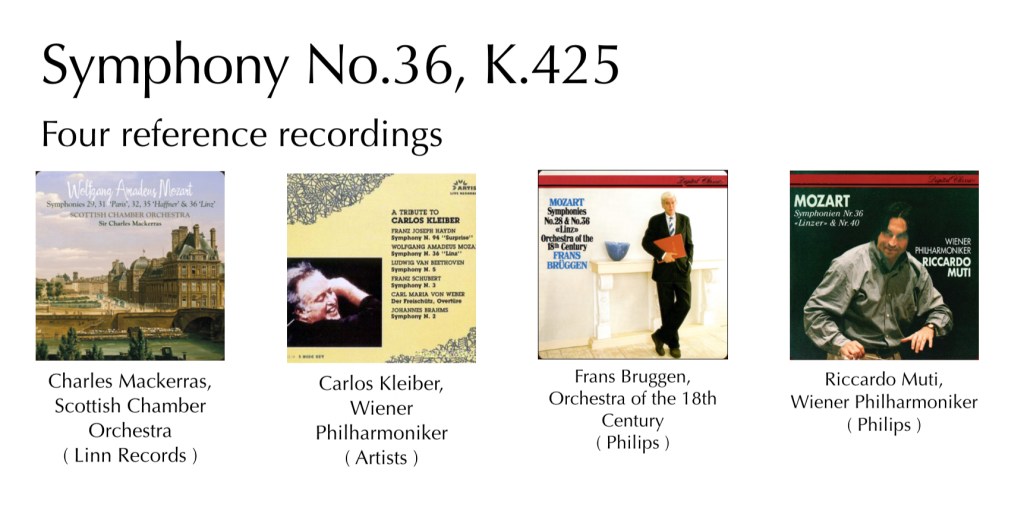

For both Christopher Hogwood, with the Academy of Ancient Music, and Charles Mackerras, with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, elegance is paramount. Whether in the introduction to the 39th, which loses all its military aspect (which is very much in evidence in René Jacobs’s version, for example), or in the first movement of the 38th Symphony, the brass loses anything that might make it sound « flashy » or « pompous » and becomes at times solemn, at times colourful and guarantors of the melodic line. It would have been unimaginable in a large post-romantic orchestra to give the melody to the brass! In the recordings of the Golden Age, Mozart’s symphonies sounded much smoother and more tender, less contrasted but perhaps also less tense and less dramatic.

In radical contrast to the smooth, post-romantic versions by Krips or even Bruno Walter with the Columbia Orchestra – Walter, who wanted to conduct Mozart as quickly as possible, no doubt also did so because contrasts were much less present in the vision of the time – Hogwood adds a harpsichord so welcome that it becomes obvious and seems to be missing from the other versions in the 25th and 29th symphonies, while the bounce and nobility are magnified in Mackerras’s 35th and 36th symphonies.

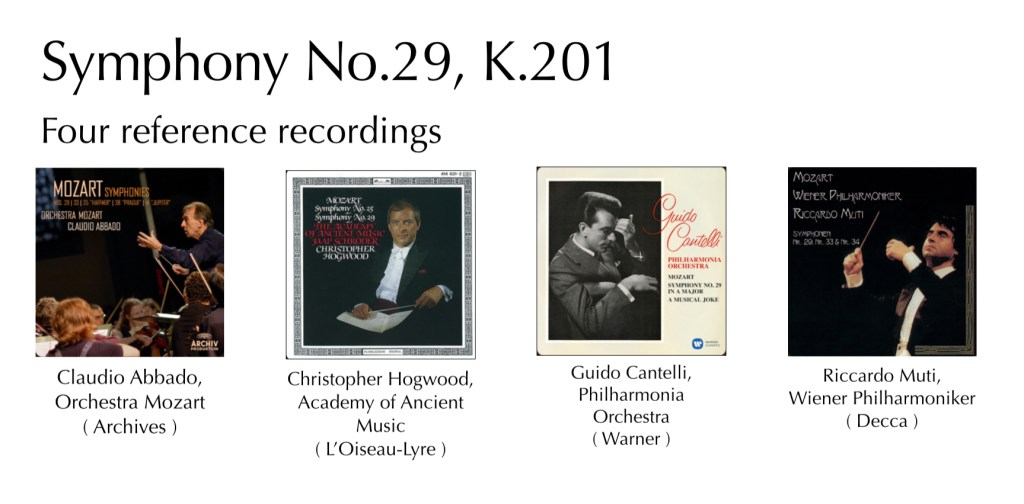

Claudio Abbado offers an ideal 29th symphony. As if in a dream, the Italian maestro’s round, in a way « swaying », phrases weave the relief of each movement, highlighting every detail – OK, I’m exaggerating, but still! – No accent is gratuitous, everything is justified, even the last movement, structured by trills in the strings.

His 38th symphony, on the other hand, raises questions. Highly contrasted and elegant, candles seem to be gradually lit in the introductory Adagio before an almost spiritual light radiates from the Allegro. But if the 38th Symphony lends itself extraordinarily well to the game of chiaroscuro, is it really written for this vision? Isn’t Abbado’s work, with its soft woodwinds, almost hushed chords and portamento here and there, a bit of a diversion? At least, I think we can legitimately ask the question, because the ‘Prague’ is also a symphony of the moment, where Abbado would ultimately make it rather nostalgic.

Perhaps there is a very simple criterion for judging an interpretation of the 38th symphony. At least I suggest it. The Allegro is repeated a great deal, even more so if there are repeats, and I often have the impression that the excellent versions make the theme so silky, supple while remaining rhythmic, and sufficiently complex that after 17 minutes you are still in the joy of the first moment. Conversely, a less accomplished interpretation will very quickly seem tiresome and, because this is the case in a sense in this symphony, repetitive.

This is the case, for example, when we compare the performances of Josef Krips with the Concertgebouw and Karel Ancerl with the Dresden Staastkapelle, this time on modern instruments. Even if Krips’s version seems formally much more beautiful from the outset, the depth of Ancerl’s version emerges little by little with each repetition, whereas Krips’s doesn’t get any thicker, and ends up, as far as I’m concerned at any rate, tiring me out.

The problem with a certain number of performances on early instruments is a kind of brutality. This is undoubtedly partly due to the reduced number of players and the different balance of the orchestra (less sonorous strings, very present brass and timpani, drier woodwinds and so on), but it can’t be just that. Why do Bruggen and Hogwood, for example, sound so much rounder and fuller?

In reality, there is a form of dryness that is perfectly appropriate, if only to bring the articulations, the attacks, the different planes and lines to the fore, in short, the relief, but sometimes these performers tend towards a form of univocity that can lead to a monolithic and even sometimes ‘first-degree’ reading, with no second meaning, no details – in short, the magic of Mozart is gone.

What is interesting to note, however, is that the contrast of performances on period instruments allows the conductors to conduct more slowly. It may seem paradoxical, but a smoother, less contrasting aesthetic demands more speed, otherwise the tension and melodic line are lost. What Bruno Walter, Wilhelm Furtwangler, Arturo Toscanini and Sergiu Celibidache have in common is that they all conduct Mozart’s symphonies at extremely brisk tempi, even though these conductors are not all necessarily fast in general.

Among these older versions, Guido Cantelli, in the 29th Symphony, manages to strike just the right balance, but by the opposite route! Where older instruments, by their very nature, needed to be softened, the modern orchestra needs to be shaped to offer more contrasts, and, especially in the case of a post-romantic orchestra like the Philharmonia here, needs to be really lightened up. And that’s what Cantelli does, using a remarkably fine orchestral texture to sculpt the symphony, adding sharpness to each new attack, while retaining the parameter already offered by the post-romantic orchestra, i.e. that silky, richly coloured sound. The tempo is natural, lively without being too hurried. So there’s enough substance to give consistency, without falling into a form of nausea, as can very easily be the case with Karajan, Bohm, Bernstein, Marriner or even Fricsay, whose 29th symphony is for me far less successful than his 35th, for example.

Karajan, in his veritable bulimia for recording, has recorded Mozart’s symphonies many times. But it has to be said that, in these works at least, the conductor has gradually become a kind of caricature of his own style, except perhaps in the Jupiter symphony. The latter was one of his hobbyhorses in concert, and his vision has only become more refined with time.

The recordings with the Philharmonia and especially the 33rd Symphony in 1946 with the Vienna Philharmonic are far more interesting than those with the Berlin Philharmonic available on Deutsche Grammophon. But even with the Philharmonia there is already that legato that runs through, and in a sense blurs, the 29th, 35th and 38th symphonies. The 39th seems better suited to Karajan’s style, perhaps because the legato manages to soften its often overly military side, while lending a real tenderness to the slow movement. But here again, the post-war version with the Vienna Philharmonic is more interesting than the one with the Philharmonia, although the woodwinds are absolutely fabulous in the latter.

The post-romantic orchestra generally lends itself poorly to Mozart, and this is particularly noticeable when listening to performances from the great « romantic tradition » of orchestral conducting. While Hermann Abendroth, Willem Mengelberg and even Otto Klemperer seem to have really « missed the point », delivering interpretations that are « out of place » because they are too violent while losing the necessary tension, the case of Wilhelm Furtwangler is more interesting to explore. Furtwangler’s interpretations are more complex, full of detail and transcended by a metaphysical force that seems to be lacking in the others I mentioned earlier.

There is an impetus, a will that surpasses the shortcomings of the thick orchestral fabric or simply outright misappropriation – because I’m not at all sure that Mozart wrote his symphonies with a spiritual or mystical intent, but that’s just my personal opinion. For all that, Furtwangler gives meaning to the 39th and 40th symphonies, and an energy that was lacking in the other post-romantic versions, even if the Philharmonia and its woodwinds had some beautiful colours with Klemperer.

How, then, to reconcile the supporters of the Romantic tradition with those who favour a return to period instruments and the sounds of the Classical period? Nikolaus Harnoncourt had the solution, with interpretations that returned to the original discourse without abandoning very strong interpretative choices. All the instruments are distinguishable, every detail is magnificently brought out, there is an extraordinary energy – which could even pass for pre-Romantic – and the dynamics are respected.

Admittedly, Harnoncourt’s conducting can sometimes display a form of brutality, but this always remains, at least in Mozart’s symphonies, sufficiently measured and, above all, very consistent with the rest of his interpretations. Harnoncourt has a real vision and brings it to bear on all the works, giving them a remarkable unity. For me, Harnoncourt undoubtedly remains the performer whose discography is the most homogeneous in these symphonies, even if I would tend to recommend the versions with the Concertgebouw and Concentus Musicus When more than those with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe – a bit in between, where the Concertgebouw and Concentus represent two more assertive paradigms in Harnoncourt’s career.

At a time when small-scale performances, often on period instruments, were already beginning to make up the majority of recordings, Sergiu Celibidache continued his post-romantic approach to Mozart’s symphonies, in Stockholm as well as in Stuttgart and Munich.

If some of Celibidache’s performances in Munich – the majority of them in fact – are, in Mozart’s music at any rate, misappropriations – starting with the Requiem, followed closely by the Grande Messe and the slow movement of the Symphony in G – I think it is far more interesting to look at what Celibidache was proposing before his arrival at the helm of the Munich Philharmonic. Celibidache’s position on tempo was actually taken from Furtwangler, who told him that « it depends on how it sounds ». And when the orchestra’s sound isn’t as rich, or when there’s simply no time to shape it as in Munich, then you have to opt for vivacity, and a liveliness that is much more suited to Mozart’s symphonies. Of course, the orchestral fabric remains very thick at times, like the introduction to the « Linz » symphony in Stockholm, or even that there are some very fine performances in Munich, like in the « Haffner » symphony for example. But on the whole, I personally would tend to prefer Celibidache in the ‘Prague’ and ‘Jupiter’ symphonies. First, let’s listen to the ‘Prague’, here with the Stockholm Radio Orchestra in 1970:

Celibidache was a metaphysical conductor, and this is evident in his interpretation of the opening Adagio. But beyond any attempt to intellectualise the interpretation, there is a real evidence of it, despite a slight lack of naturalness. Celibidache reminds us that ‘Prague’ is also a work full of freedom, a freedom that can even become physical at times. Even if there is a beautiful tragic force in the introduction, Celibidache gives us to understand from the very first chords that this is destined to be overcome, to be supplanted by light. The latter is embodied in the obvious formal beauty of the performance, starting with the sound of the strings and woodwinds, but also in the overall vision proposed by Celibidache.

Today, however, the consensus is on the revolution initiated by Harnoncourt, and the forces are much smaller than at the time of the Golden Age, and ensembles on period instruments are much more widespread. Mozart has rediscovered contrast, and tempi are not as uniformly rushed as they might have been in the early days of period instruments. Mozart’s symphonies have thus retained their brilliance while rediscovering a form of drama and theatricality that they lacked in the post-romantic aesthetic, which had made them too stale in certain respects.

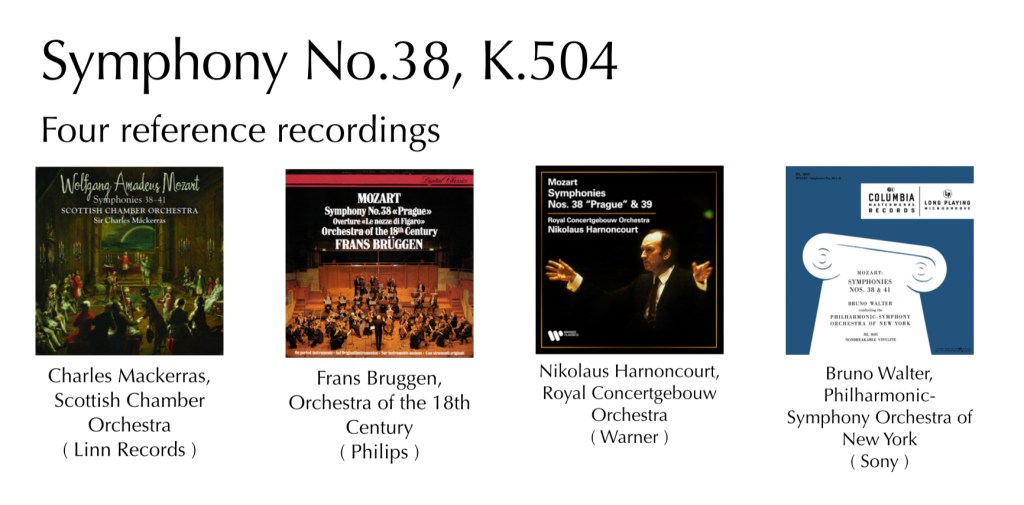

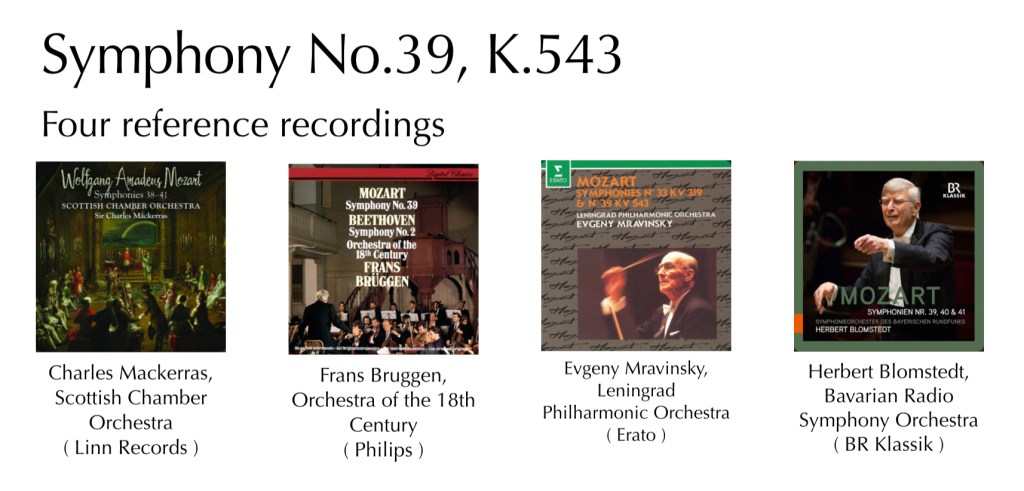

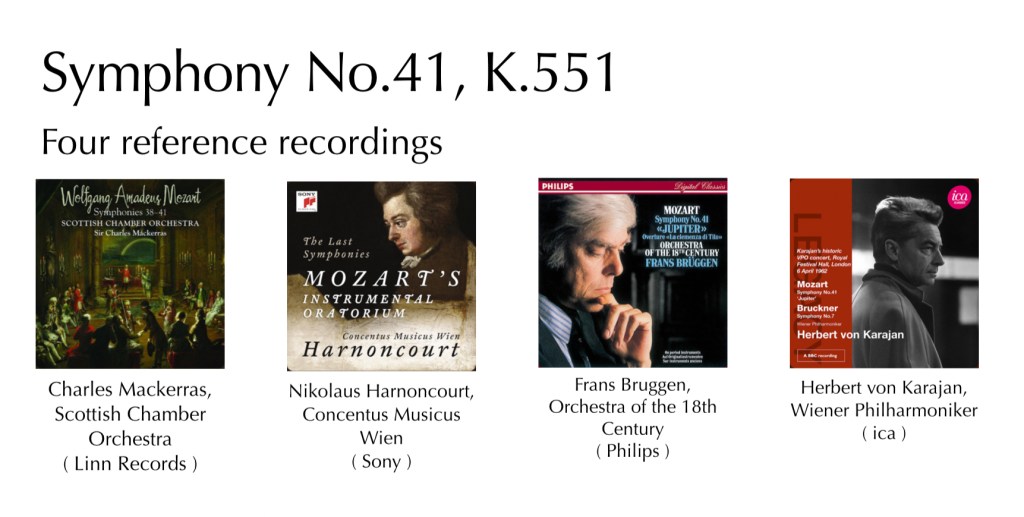

And to finish this article, I I would like to suggest you a selective discography for each of the major symphonies.

Laisser un commentaire