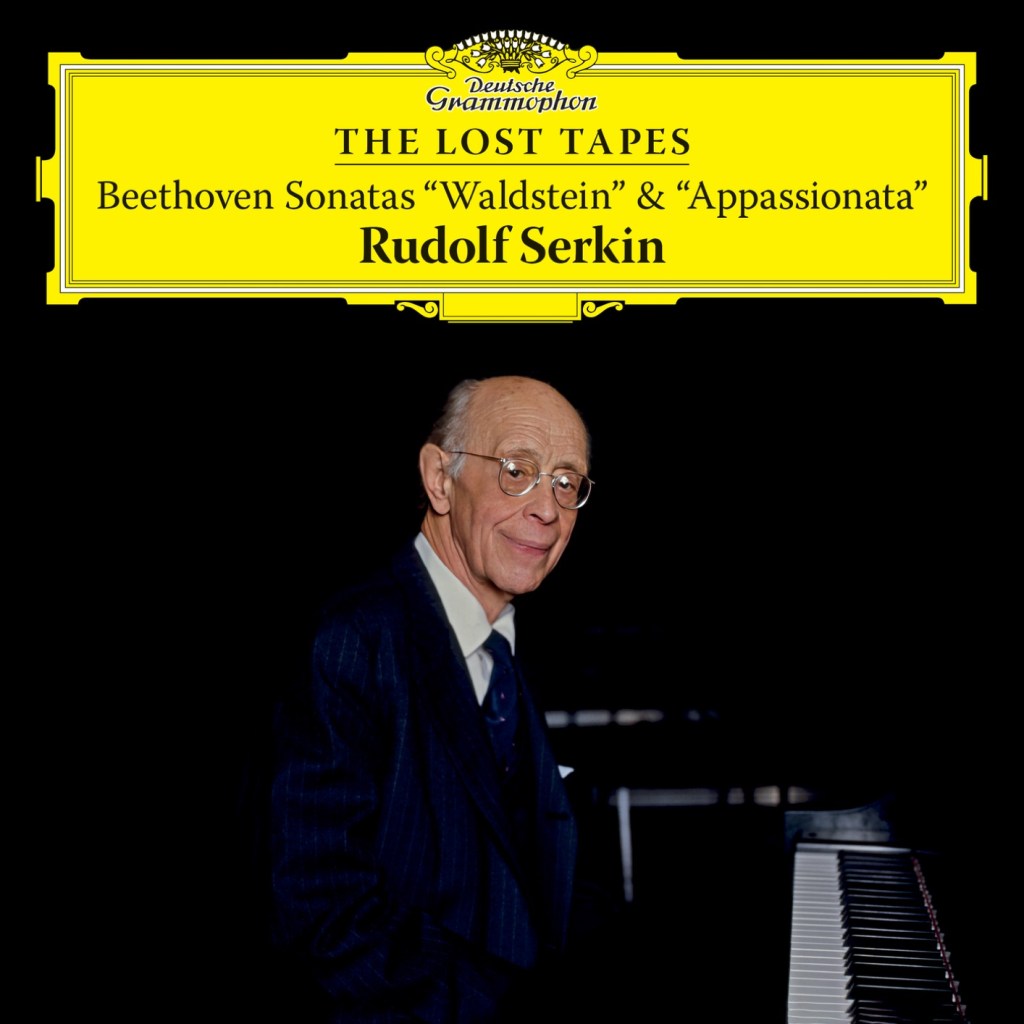

On this Friday 17th November, Deutsche Grammophon released two « lost tapes » by Rudolf Serkin, dated 1986 and 1989. The album contains two previously unreleased versions of the ‘Waldstein’ and ‘Appassionata’ sonatas, which the pianist was unable to validate. His daughter, Judith Serkin, agreed to publish these recordings, and also wrote the introductory text that appears in the booklet. I think we have here one of the most precious testimonies to Serkin’s art, both from the point of view of sound – through the recording – and through these interpretations in themselves, at the end of a life span of several decades.

We have several – to put it mildly – great versions of Beethoven’s sonatas Op.53 and Op.57 by Serkin. It’s often said, and I fully agree, that Serkin was better live. He seemed freer, stronger, more spontaneous and natural. However, Serkin never took a back seat to the music itself, never fell into any form of blandness. Admittedly, some of his studio recordings are a little stiff, but they retain a total elegance and legibility. The difference between studio and live is mainly to be found in the sound. In the studio, there is a kind of emphasis on the pure text and the different lines, to the detriment of colour and dynamics, whereas live, the clarity of the speech is always present, even though it is combined with a wide sound, powerful phrases and an extraordinarily wide palette of colours. This quest for clarity and beyond obviousness does not prevent an absolutely enormous breadth from expressing itself with force and sometimes even ardour – the ‘Waldstein’ sonata performed live in London in 1973 is a marvellous example of this, which underpins the critics’ appreciation of Serkin’s live performances. So what do these two studio versions, which are extremely late in Serkin’s career, contribute? Everything! All the potential that had never been released in his previous recordings is here, magnified by superb sound quality. The colours are in the service of clarity, and all coldness has completely disappeared in the service of an interiority, an immanence that is not in retreat; there is no longer that timidity, that shy aspect that could be found in the previous recordings of the two sonatas.

Serkin allows himself to be carried along by a constant flow, contemplative but also very sombre. It’s a vision on the edge of the abyss, and even in a reflective sense. There is a kind of mirror, a reflection in any case, and this is all the more apparent in the liquid rendering of the first and third movements of the ‘Waldstein’, which plays on a stunning modulation and alternation of textures. Serkin is extremely narrative here, sometimes melancholic and sombre, sometimes heroic and even daring. And all this as if on the edge of the abyss, with a mastery that sets a grandiose framework for the narrative’s particular purpose. There’s such a sovereign balance that maintains an overall framework for the narrative to truly tell a story, but this doesn’t prevent Serkin from finding his moments of brute force often characteristic of his live performances, and then an absolute delicacy and tenderness. This underpins the reflexivity of this vision, which seems a synthesis of everything Serkin has done before he set off into the light.

And while certain shadows do seem to permeate the work, they are not directly dark. In fact, they are often more means than ends. For example, in the case of the transitions, whether to the last movement of the « Waldstein » or to the « Appassionata ». The latter is incredibly passionate, even though Serkin’s interpretation – perhaps due to his declining technical abilities – is extremely analytical. And that’s what makes this disc a real gem: it’s analytical, you hear everything, you seem to be rediscovering the text itself. Every keystroke is marked with insane precision! And what we glimpse here that we didn’t directly perceive in Serkin’s interpretations is an art of silence. The music breathes through modulations and through silence itself. Serkin plays on all the possible registers to create infinite nuances, and plays between the coloured timbres to convey an immense wisdom. Wisdom has at last been combined with strength, and at last we find these two aspects of Serkin’s art that were so far apart between the studio and the stage. These performances are to be compared with those of the last three sonatas, in Vienna in 1987. On each occasion, it is as if Serkin had adapted the work not only to his admittedly declining technical abilities, but above all to an absolute, necessary vision, the one that we find composed of all the previous performances. Serkin possessed this science of phrasing, detailing all the different lines, bringing the different planes into dialogue, and using dynamics to gradually bring out the inner relief of the works. Wilhelm Furtwangler said that what makes a great performance is when « the details cease to be details ». And Serkin, who placed them in the background in his previous recordings without ever undermining them, simply integrating them into the general discourse, which constitutes the foreground and the overall line of his interpretations, brings them out here with the greatest joy! The details have become the essentials, but it’s because the general thrust is carried along by such mastery that we can pay attention to them in these two tapes.

You absolutely must hear these two performances of the ‘Waldstein’ and ‘Appassionata’ sonatas! Each phrase is a world in itself, and at last we find the perfect synthesis between Serkin’s sense of detail and reflexivity in the studio and his ardour and freedom in an analytical form that still reveals aspects of these famous works. Deutsche Grammophon offers here a sumptuous testimony to the art of one of the greatest artists of the twentieth century.

Laisser un commentaire