Liveliness is an essential characteristic of Lipatti’s playing. With the Romanian pianist, time never seems to stand still. At first, there is something calmer, without being frozen – which would be in contradiction with the moving and temporal character of the music. Some performers place their interpretations in a moment as if out of time and space, as if in another world, hoping for something else. Alfred Cortot, who was one of Dinu Lipatti’s teachers, said in a filmed masterclass – which can be found on YouTube – about the closing piece of Schumann’s Kinderszenen’: ‘It seems to me that the last piece, « The Poet Speaks » – that is the title Schumann himself added to this immortal page – should be transposed to a more intimate plane of reverie [. …], not only the beautiful sonority, the expressive relaxation of the phrase, but a more dreamy feeling. The truth is that this last piece should be dreamed, not played. So there is a difference between performers who ‘dream’ the music, who transpose it out of time to evoke what is real in dreams, imagination or hope, and performers who, as Lipatti seems to me, condition their playing by taking into account the temporal reality of the music. Firstly, it is not a question of ‘denying’ time, and secondly, it reveals what is real as a result of the dream, the imagination or the hope: the dream is made intelligible, it is not passed through in front of the spectator, it is returned to him as a result of work done upstream. The great performers nevertheless retain this ability to give the impression that the music is created in the moment, making the music real and organic to the listener’s senses, and time is part of Lipatti’s playing, it is not outside the performance.

Lipatti’s interpretations embody and breathe the obvious, in a form of simplicity. This – apparent – simplicity makes intelligible a musical purpose that is always clear, and this is also what allows the listener to hear, without altering it, all that may constitute the complexity of the piece.

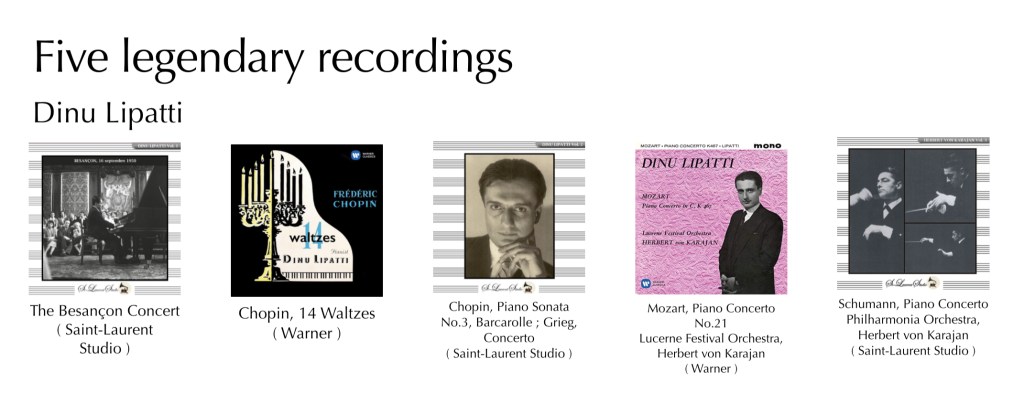

Lipatti thus remains a humble interpreter, rather like Cortot. Alfred Cortot’s style was characterised first and foremost by a great humility in the face of the composition; the performer placed himself at the service of the music, and this gave rise to a profoundly sincere attitude in the way he played. If there is always a great clarity in this way of interpreting, in Cortot as in Lipatti, one must not neglect either the shadowy or the virtuosic part that characterises them. Both Lipatti and Cortot adapt to the work and what it demands, and this is also what allows Lipatti not to add excessive feelings – which would be superfluous – to works that are already very dark or complex – as his interpretation of Chopin’s third sonata proves, the slow movement is already tortured, Lipatti’s work is a formidable highlight – or to give seemingly simple or lighter works, such as Chopin’s Waltzes, a complex or interior character – rather like the dialogue between the performer and himself that one might hear when Claudio Arrau plays Chopin’s Nocturnes, for example.

Cortot told his students that ‘the nationality, the period, the individual character of the author, his degree of culture, the events of his life, the environments he has passed through, his very readings, having influenced his creation, a special adjustment for each work, will be indispensable to the interpreter who claims to bring it to life. Not only is the quality of Cortot’s teaching embodied in the diversity of style of his various pupils – whether we are talking about Dinu Lipatti, Clara Haskil, Pnina Salzman or Marcelle Meyer, for example – but each of his pupils knows how to adapt to the composition and to what it requires. For example, Lipatti’s playing is not at all the same – although there are similarities – if he plays Ravel – Albodora del Gracioso – or Mozart. In both the teacher’s and his pupil’s style – both of which have had a considerable impact on the history of interpretation – there is an unprecedented sense of detail. The difference lies perhaps in a form of liveliness and lightness in Lipatti’s style, whereas Cortot works more on relief, thus emphasising contrasts. In Lipatti’s case, it is the liveliness that hollows out – one might even say ‘sculpts’ – the work and gives it its depth.

Where Lipatti’s style is more terrestrial, Cortot’s is more metaphysical, although both seem to emphasise the nobility of the works. This is particularly the case when listening to Lipatti’s Mozart’s Eighth Sonata – K.310 – or Cortot’s performance of Bach’s Fifth Brandenburg Concerto – BWV.1050, with Jacques Thibaud, Roger Cortet and the orchestra of the École Normale de Musique. Both pianists are thus more assertive than questioning – indeed, Cortot has a great mastery of silence – whereas Clara Haskil – for example in Schumann’s ‘The Poet Speaks’ – is in a sense reconciling different answers to the questions raised by the performance of the piece – if not the piece itself.

Lipatti gives a particular relief to the pieces he performs. This is particularly evident in the way the pianist works on the transitions between the different parts of a work, which largely ensures its overall coherence. This is what makes his interpretation of Chopin’s Barcarolle, in addition to its rich, colourful sound, an almost absolute reference. Relief is a constituent element of the complexity of a piece, but all the colours to be found in Lipatti’s sound – in good transfers, too much filtering of the 78rpm is tantamount to losing precious frequencies – add to the coherence of the works. We can notice various aspects of this in Bach’s first Partita, or in the slow movement of Chopin’s third sonata. It is also a focus on special, unique details that allows Lipatti to lift Chopin’s Waltzes from the anecdotal character that seems to follow them in so many performances. Finally, even if Cortot, Sofronitsky or Arrau offer complex and profound interpretations, it is indeed with Lipatti that the magic seems to irrigate each waltz with a new brilliance, sometimes brilliant, sometimes joyful, but also sometimes tragic or in-between – we often underestimate, I think, the role of the « in-between », of uncertainty in music, whereas it is what can give it all its narrative force.

Adapted from my intervention in the programme « Philosophie au présent » on Aligre FM: https://youtu.be/8JRNfHVNF2I

Sources :

Alfred Cortot, « Le poète parle » : https://youtu.be/aWr36hIgIuU

Citations d’Alfred Cortot : Wikipedia

Laisser un commentaire