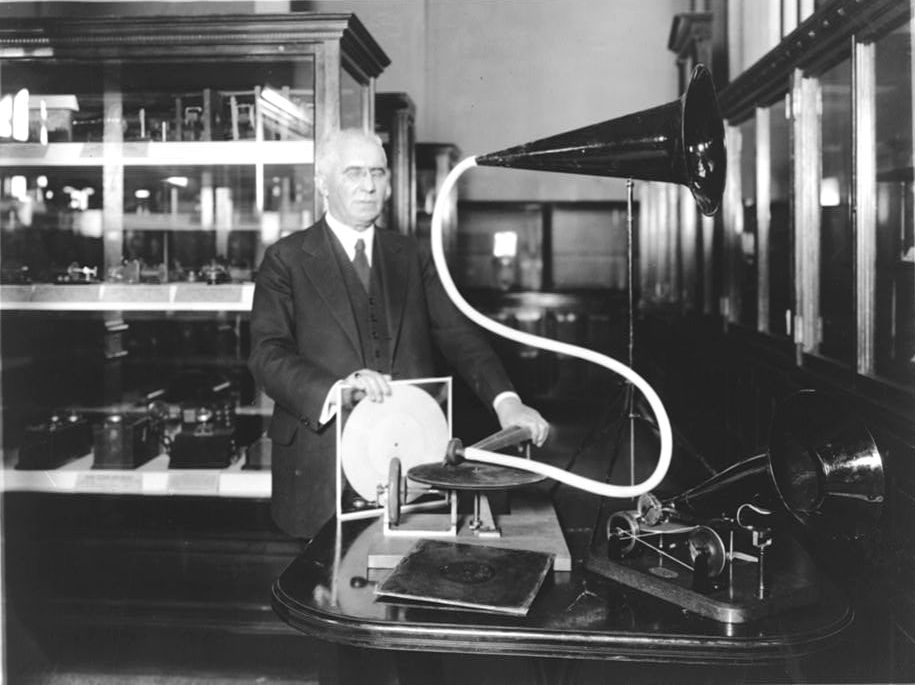

Emile Berliner with his recording gramophone.

The sound identity is part of the record. Certain technical constraints, such as the medium and its limitations, microphone placement and the sound spectrum, shape and modulate this sonic identity. And the performer is obliged to adapt to them. But these conditions have changed considerably over the course of the history of recording, which is why it is important to return to them when assessing the performance itself.

This is particularly true of performances from the 78 rpm era. Although electric recording made its appearance in 1925 – and Dvorak’s marvellous ‘New World Symphony’ conducted by Stokowski, before that recordings were acoustic and the sound spectrum extremely reduced, because of the horn in which the sound was captured – the medium on which the recording was transcribed remained the 78 rpm, until the arrival of the 33 rpm LP. So while sound quality improved considerably, and recordings quickly became excellent – Saint-Saens’s Piano Concerto No.4 by Cortot and Munch is an excellent example, as are many HMV recordings from this period – the constraints of 78 rpm remained. As a result, recordings were still made in takes of extremely limited duration, one side of a disc being around 4 minutes long, or 8 minutes for a record.

With 78 rpm, the performer had to adapt his or her interpretation, particularly through transitions, to the connection of sides, because, obviously, all the movements are no less than 4 minutes long! The 33 rpm era and the editing of takes were made possible by tape recording, which revolutionised both recording and listening conditions, by reducing parasitic noise and making it possible to record for much longer.

The advent of the 33 rpm, as well as allowing much longer takes – even if this actually encouraged even more editing – also artificially relegated the interpretations recorded on 78 rpm to the status of obsolete material. In order to preserve certain historic and popular recordings, they were filtered to ensure their continued distribution. The 78 rpm record had another major drawback, which interfered with the listening experience – and still does for many people today: its very high level of frictional noise. As the background noise of 33 rpm was reduced to a few slight creaks, completely inaudible compared to 78 rpm, immediate comfort was immediately favoured. Walter Legge, EMI’s famous producer, got rid of his entire personal collection of 78s for this reason.

But filtering inevitably means losing frequencies. And so these historic interpretations have been stripped of a not inconsiderable part of their compensation, effectively cutting the interpretations down to size! Cortot or Lipatti sounded like cardboard, the Vienna strings under Walter acid, Yves Nat had neither bass nor treble, and so on. Each of these immense interpretations recorded thanks to the 78 rpm recorder – that’s what made it possible to freeze them, let’s not forget! – had been torn from their deepest souls, had lost their identity, both sonically and artistically.

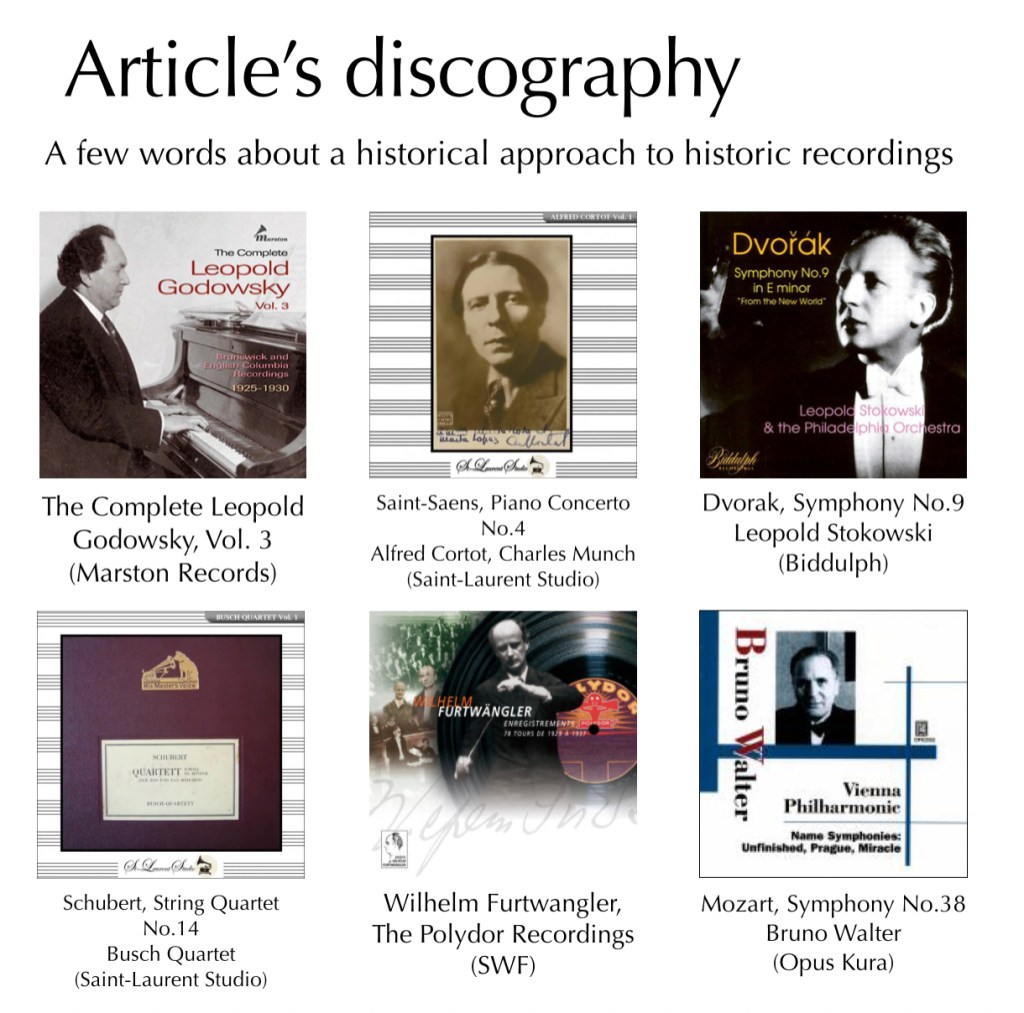

What has been made possible by ‘historically informed’ methods of acoustic renovation, in particular with the particular touch of the record company, which are relatively recent – we can think of collections such as Naxos Historical, Biddulph, APR, then independent labels such as Saint-Laurent Studio, Marston, Opus Kura, and then we must mention the extraordinary work on YouTube of certain channels such as Uchukyoku1, or Pianissimo at Midnight – is to rediscover the digitised sound of the original 78 rpm. Since 78 rpm is the basic medium, any 78 rpm of the period is just a copy that is similar in every way to the original record – which is why the renovation can be based on any vintage record, as long as it’s in good condition. But listening must adapt to the constraints imposed by the 78 rpm record. We have to see 78s as a positive condition for appreciating these interpretations. Not filtering means keeping all the richness of the sound spectrum that has been captured thanks to electric recording, and then, from a purely psychological point of view, it’s like cognitively returning to the era, finding yourself face to face with the performer, with that organic grain of the analogue recording.

Even if filtering editions offer immediate comfort, this is putting one’s personal listening experience above appreciation of the interpretation, in ethical terms subjecting the interpretation to the listener’s comfort, when it is the opposite that should be prescribed! Historical character and quite simply artistic considerations cannot be subordinated to comfort insofar as the latter limits them, and in fact distorts them. And the legacy of the 33 rpm editions has lasted for a long time, first in the CD editions that came directly from them – no work was done on the sources, even though they were numerous because they were published in large numbers at the time -, then in the digitisation of 78 rpm records before filtering them to the same level, even if ‘better’, with a view to selling them, commercial considerations taking precedence over historical preservation – not to mention artistic considerations.

Labels therefore have an ethical responsibility when it comes to historical treasures, fundamental milestones in the history of interpretation – quite apart from any consideration of the validity of these interpretations. And that’s without mentioning all the ‘masterings’ that in reality refer to an equaliser placed to artificially colour these recordings. A recording made on 78s that no longer has surface noise poses problems anyway. And for the time being, even if the situation has improved considerably, it is still on the whole small independent labels, many of which concentrate solely on publishing historic recordings – and that’s not the best thing, especially when much more famous labels publish the same recordings, even if the technical and sometimes even editorial work is not as good – that are working to preserve these recordings.

Laisser un commentaire