Rudolf Kempe is not the most talked-about conductor, and yet! Of course, Kempe’s name is still associated with Richard Strauss, and he was one of the greatest interpreters of his orchestral works, alongside conducting giants such as Herbert von Karajan and Fritz Reiner. The symphonic poems and symphonies were perhaps never as lively, natural, spontaneous and lyrical as under his direction – in short, everything that Karajan lacked, but which he made up for with all the sensuality and almost innate orchestral science that he knew how to infuse into them. His Also Sprach Zarathustra, Don Juan, Till Eulenspiegel and Bourgeois Gentilhomme are embodiments of all the mischief and playfulness that Strauss the composer could display, without intelligibility or balance ever taking a back seat. Moreover, this vision is in line with that of the composer in his interpretative choices, who generally advocated lightness and vivacity.

But apart from Richard Strauss, Rudolf Kempe’s discography contains some marvellous recordings. His German Requiem by Brahms is one of the greatest of all, as is his Mozart Requiem – albeit a little more dated – and of course Kempe was a marvellous opera conductor: his Wagner works – his Tetralogy and of course his Lohengrin – remain benchmarks – sometimes a little too clear-cut, in a sense – as do his Strauss works – The Knight of the Rose and Ariadne auf Naxos in particular. Kempe thus remains an example of what a modern conductor can be: light, clear, sometimes brilliant or grand, but always at the service of the composer above all else.

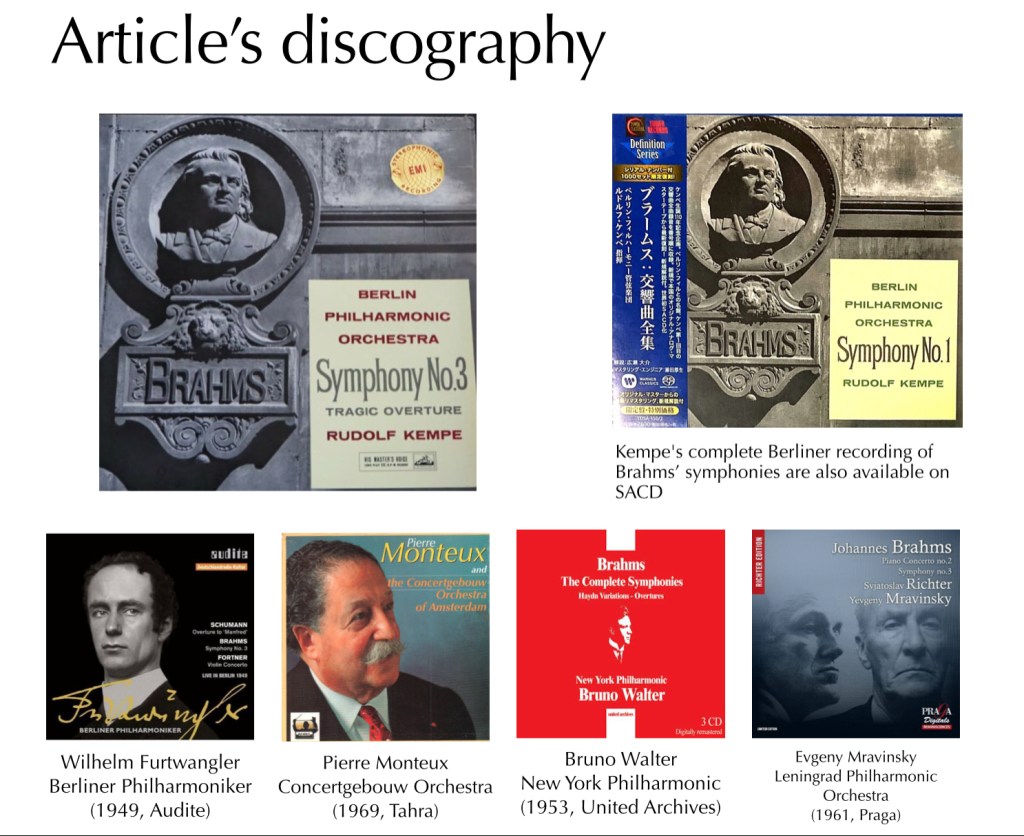

But today I’d like to talk to you about a recording that demonstrates the immense symphonic conductor that Kempe was: his third Brahms symphony, recorded in 1960 with the Berliner Philharmoniker (available from EMI, now Warner). Here we find all the essential characteristics of Kempe’s art: very brisk, even very fast tempi, a lightness that serves the dialogue between the instruments, and a marvellous lyricism – each section sings magnificently.

Kempe thus achieves a feat that only a handful of conductors have managed: he succeeds in giving Brahms’s music all its narrative force without denying the legato. Brahms’s music is undoubtedly first and foremost a matter of relief, and in this sense the great Brahmsians, starting with Mravinsky, Monteux and Walter to name but a few – for each of them is the author of a marvellous interpretation of the Third Symphony – do not particularly play Legato – on the contrary, as far as Mravinsky and Monteux are concerned, and even if Walter is very lyrical, he also shears the relief well. In a sense, Kempe is closer here to the conducting of Furtwangler, who in 1949 (live recording available from Audite) managed to give the Third Symphony all its strength, even its vitality, while at the same time sketching, painting as much as sculpting. Above all, Kempe avoided the pitfall that Celibidache fell into by over-painting the tempo: Kempe conducts quickly, very quickly even at times, particularly in the last movement, which gives it its tragic, heroic and dramatic aspect! This is an extremely theatrical performance, in which every contrast is emphasised without the melodic line ever breaking. There is always continuity, and this is what allows the different moods to flow together so wonderfully.

Brahms’s Third Symphony is not at first sight the most unified of the composer’s symphonies, and this is an opportunity to take a closer look at the work. For all the violence that runs through it and drives it, Brahms’s Third Symphony is above all a work of peace. Each movement ends in a calm that overcomes – almost dialectically, in a sense – the torments that preceded it, and each soaring movement is far more lyrical than heartbreaking. And while this assertion is obviously always put to the test when listening to interpretations, it is not objectively true; you only have to listen to Furtwangler or, of course, Mravinsky to realise the torments that can emerge and run through the work, these tormented moments culminating in particular in the Finale, each of which is constructed in a vertical and luminous rhetoric.

The Third Symphony is above all a dialogue, in which all the instrumental families respond to each other in a succession of themes, all more or less vertical – indeed, in this symphony, two movements built entirely in verticality, with sharp and sometimes even cutting attacks, frame two movements that are entirely horizontal, oscillating between tenderness and complaint, and this is borne out by the cyclical construction of the work, since the last chords are similar to the first. And like the families of instruments, it is the themes and evocations that dialogue and respond to each other throughout these four movements.

The first factor in the internal coherence of the work is undoubtedly the recurrence of themes that answer each other and recur throughout the symphony, repeating regularly from one movement to the next. And so Kempe put the constituent elements of his interpretative style at the service of coherence, and this is how his Third Symphony came to be as much an artistic unity, a single work, as a diversity in terms of moods and above all emotions. Here we find vivacity, lightness, tension and even restraint, a ‘virtue’ that was not to be found in Furtwangler’s 1949 work, the interpretation that Kempe is perhaps closest to here. So I encourage you to go and listen to this complex, infinitely rich interpretation, which can be listened to several times and always finds something new, and above all which, for my taste at least, is an absolute benchmark for its sense of balance and extraordinary naturalness.

Laisser un commentaire