It is astonishing to note that Wilhelm Kempff’s style has only become wiser. However, it would be more accurate to say that it was a step towards wisdom. In the great German master’s late recordings, ardour has given way to idealism, but imagination has never dried up. Where many pianists would be confined to a form of recitation, Kempff’s interpretations breathe wisdom with an ever-renewed purpose, and this is because imagination remains the predominant element. Kempff’s interpretations are extraordinarily narrative, the pianist telling us an ever-changing story, adapting to the spirit of each work. Sometimes with contemplation – in Brahms in particular – sometimes with vigour – undoubtedly the greatest recording of the Beethoven concertos, with Paul van Kempen and the Berlin Philharmonic -, sometimes with nobility – the famous complete Schubert sonatas -, Kempff always offers a reflection that sends the listener back to his or her own conscience: the interiority of Kempff’s interpretations is communicative. But this does not prevent the power of the sonority or even the musical flow from expressing itself when the spirit of the piece requires it, as can be clearly seen in Beethoven or Schumann, for example. But there is always a deep inner reflection in Kempff’s interpretations, and although there is clearly more expressivity in his early recordings, particularly those from before the war, this was always felt, it was already present, much more so even than in power. Under Kempff’s fingers, each phrase becomes, thanks in particular to ornamentation of astounding formal beauty, a stone laid towards the construction of an ideal. This is undoubtedly also why Kempff is so highly regarded as a reference in so many works: the vision remains personal, but what we hear above all is the work, the exact opposite of Vladimir Horowitz, for example. It is in his pre-war and 1950s recordings that his imagination and inventiveness are most evident, with sometimes unorthodox – though always measured – choices, and that his expressive power is most apparent. The interpretations of the later period are much more discreet, even if they show almost total respect for the score.

But if there were only one miracle to retain from Wilhelm Kempff’s considerable – colossal, even – legacy, I think it would be this 1936 Hammerklavier Sonata. The balance of the first two movements is sovereign, served by an enormous sonority and a truly unique imagination. The ornamentation is breathtakingly natural yet immensely refined. Kempff’s naturalness in allowing the music to breathe is remarkable, as is his emphasis on silence. The pianist does not hesitate to play the piano, the voices sing admirably and never cease to dialogue in extraordinary harmony, Kempff seeming to be truly sketching out an ideal. The Adagio is an expression of hushed anguish, of an inner dialogue seeking an answer in a glass labyrinth. There is total contemplation here, even though the pianist makes no attempt to circumvent it; he puts the obvious above all else, and here this obviousness is more than ever absolutely overwhelming. The pianissimos are so gentle, and the delicacy of the end of the movement – and of course the entrance to the next – is supremely elegant. Freedom is embodied with phenomenal vitality in the final fugue, with, once again, voices singing with extraordinary clarity – the comparison with Edwin Fischer playing Bach might even be apt.

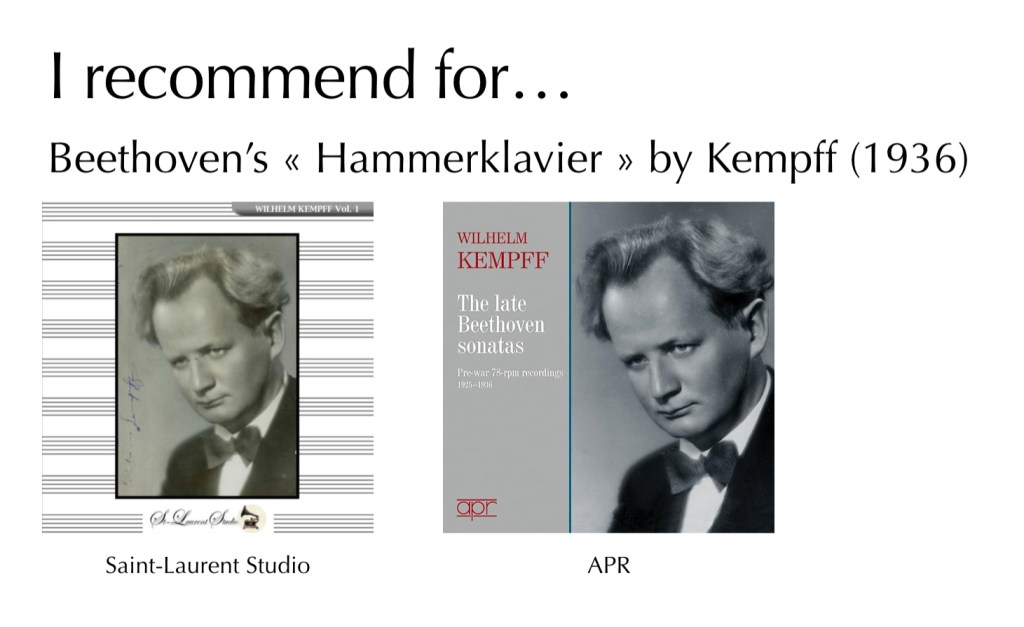

What runs through this performance from start to finish is a sincerity, a truth that perfectly embodies the universality of Beethoven’s music. One senses all the measure and intelligibility of Kempff’s style, but without the muted restraint – perhaps a little too much in the Stereo version – that would come years later. To conclude, while I recommend first and foremost the report of the Saint-Laurent Studio, restored from an unfiltered 78 rpm – because when you filter out surface noise you end up irretrievably losing frequencies that belong to the musical discourse – those who are too annoyed by the rubbing noises can turn to the APR edition – they can also find all the last sonatas, recorded at the same time, on the same double album.

Wilhelm Kempff, whether regarded as a virtuoso or as a discreet reader who made the text intelligible above all else, is unquestionably one of the most influential pianists of the twentieth century. His life spanned practically the entire century, and he remains an inexhaustible source of inspiration and an essential influence for generations of pianists.

The best report available on YouTube ( on uchukyoku1’s channel )

Laisser un commentaire