Table of content

THE HISTORICAL VERSIONS: Fiedler, Weingartner, Mengelberg, De Sabata, Toscanini, Furtwangler, Kletzki, Abendroth, Busch

THE GOLDEN AGE: Karajan, Walter, Beinum, Jochum, Stokowski, Klemperer, Reiner, Knappertsbusch, Schuricht, Bohm, Mravinsky, Schmidt-Isserstedt, Kempe, Szell, Kubelik, Gielen, Rosbaud, Bernstein, Sanderling, Celibidache, Giulini

THE MODERNS: Kleiber, Haitink, Muti, Wand, Abbado, Mackerras, Chailly, Rattle, Ticciati, Blomstedt

THE HISTORICAL VERSIONS

In 1930, Max Fiedler and the Berlin State Opera Orchestra recorded one of the earliest Brahms fourths in the history of recording (available on the Music Lover YouTube channel). This is an interpretation in the purest Romantic tradition, with radical variations in tempo and mood, revealing the inner tensions of the work with great acuity. For all that, there is considerably less mannerism than in Mengelberg’s (1938, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra), even if this also means a little more lukewarmness, and certain drops in tension – perhaps due to the recording of the time, and perhaps also to the delay.

The performance by Felix Weingartner, who conducted the London Symphony Orchestra in 1938, has aged considerably. The strings are plaintive, despite the speed, the relief is lacking. The recording prevents us from hearing the woodwinds, and some moments are even brutal. The whole thing lacks coherence and is full of mannerisms. Finally, this rather objective and smooth conducting lacks a bit of soul.

In 1938, Willem Mengelberg and his Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (available on YouTube on the Uchukyoku channel1 ) offered the quintessence of the romantic tradition of Brahmsian interpretation – much better than Fiedler’s and Abendroth’s versions. There is an incredible energy here, an urgency, but also a real bravery. The conducting is certain, extremely narrative, Mengelberg was able to reconcile the opposites incredibly well, varying the tempi in a way that is unimaginable with other interpreters – even Furtwängler doesn’t go that far! -while remaining formidably coherent. Above all, there is an overall vision, a meticulous conception – Mengelberg was a dictator in front of the orchestra – to highlight each dramatic aspect of the symphony. There is an internal logic, a vision which, even if it remains inherently divisive, remains unequalled in its genre.

With the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in 1939, Victor de Sabata delivers an interpretation in which opposing forces clash with an ever-renewed sense of drama and tension. The strings are of magnificent lyricism – the second movement! The strings are magnificently lyrical – the second movement! – and the discourse is highly theatrical. This is an extremely narrative performance, with de Sabata emphasising every internal tension in the work to bring out different meanings, and making the complexity of the work truly intelligible. The sound of the BPO is absolutely magnificent, we have here an absolutely magnificent version, unequalled in the narrative.

Is Toscanini’s Brahms that clean-cut? Is it so dogmatic or sharp? Although some have said that Toscanini was « being racist » in Brahms, his Fourth rises to the occasion with a vital, earthy energy but with absolutely phenomenal expressive power. It is certainly not a metaphysical reflection, nor even a revelation with a stake, but it is indeed a profound and above all lively reading, which restores Brahms’ music to its full strength in an organic, almost protoplasmic vision, with, whether with the NBC Symphony Orchestra or the Philharmonia, an orchestral sound that is far more exhilarating than in his Beethoven.

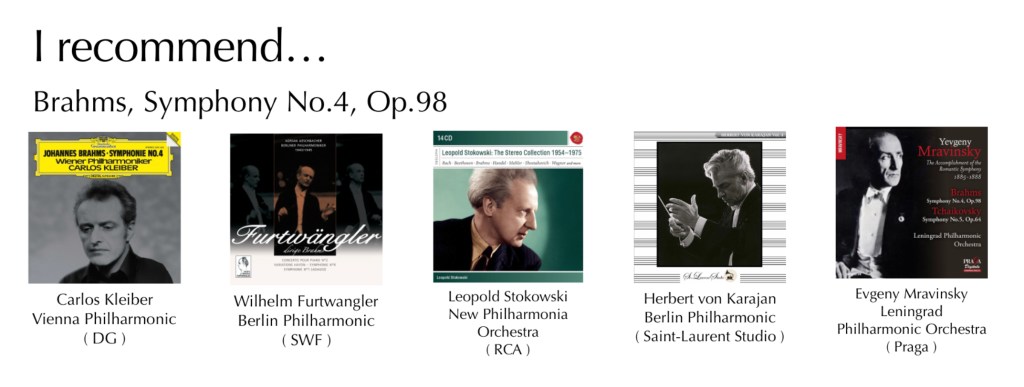

Wilhelm Furtwangler, or the romantic vision without any mannerism, without any excess in the manner of Abendroth – more at ease in the third symphony – or Mengelberg – better in the first and third symphonies. The German conductor combines an organic strength – more than energy – with a pain that oscillates between a form of flight forward and a real feeling of powerlessness. But the expressiveness of Furtwangler’s conducting of Brahms lies more in this way of painting than sculpting – something he is probably the only one who really succeeds. The variations in tempo are numerous, but it is above all naturalness that dominates – even in the most extreme passages, which are paradoxically never in excess. As for the versions, if 1943 (in the recent boxed set of war recordings published by the BPO, or the French Wilhelm Furtwangler Society’s edition) is undoubtedly the most violent, it is perhaps also necessary to turn to 1948 (Audite), an excellent synthesis of Furtwangler’s art, the recording of which is a little less precarious. Mention should also be made of the formidable live performances of 1949 in Wiesbaden ( Tahra ) and 1950 in Salzburg ( Orfeo, of which we hope for a better edition soon, even if the YouTube channel Pianissimo at Midnight, whose reports are worth a diversion, has already published it ).

Paul Kletzki, in Lucerne in 1946 (Audite), offers a dishevelled vision, of great violence, almost an uppercut. It is a meteor, an energy made of stone that animates a score that seems to live as if in suspension one last time. Even more than violence, it is perhaps even rage that runs through this interpretation, admittedly a little monolithic at times. But there is an overall vision here, and a direction that literally takes everything in its path, holding the spectator hostage for forty minutes.

Hermann Abendroth’s interpretation with the Leipzig Radio Orchestra (Berlin Classics) is certainly in the spirit of the Romantic period and pushes the intensity to new heights, but it lacks coherence – unlike the fabulous Third Symphony, which is on the same disc. The choices are pushed to the extreme, and the moments follow one another brilliantly without always convincing. Indeed, the differences in atmosphere are sometimes so great that the conception seems to be won over by a certain amount of mannerism. Moreover, a kind of overflow of emotion ends up losing all nuance, the vision deserves more restraint, and at no time does the balance really seem to be found. If we are to listen to a vision from the 19th century, we might as well look to Mengelberg and, of course, Furtwangler.

Fritz Busch, with the Vienna Symphonic Orchestra in 1950 (version available on YouTube on 1Furtwangler’s channel), uses his usual sense of line, clarity and powerful energy to serve the expressiveness of the score. The discourse is taut, the line is never lost and there is a permanent tension that runs through the whole work. The expressiveness thus lies as much in the melodic line as in the lyricism of the string phrases, and the ensemble is thus both powerful and supple, despite the less than ideal orchestral timbres. An excellent version, which every Brahms fan should have heard.

THE GOLDEN AGE

Of all the versions that Herbert von Karajan left us, the live recording from Paris, at the Théâtre des Champs Élysées in 1975 (Saint-Laurent Studio), is without doubt the most important. The refinement here is brought to a peak, without ever hindering the spontaneity of the interpretation. The lyricism of the strings is amplified by the legato, rather well compensated for by the rather dry acoustics of the concert hall. The overall balance and colours do not prevent the incredible density of sound, an exceptional narrative capacity of the discourse, and above all an incredible intensity. The sound of the Berlin Philharmonic is absolutely exhilarating, and yet there is a palpable tension, a form of urgency that cannot be found in any of his studio recordings – not even the formidable performance with the Philharmonia Orchestra. If there is a flaw, it is in the profusion, which pulls Brahms towards Richard Strauss – even if this profusion does not prevent a phenomenal power from being expressed.

Bruno Walter, conducting the Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra of New York in 1951 at Carnegie Hall (live, published on YouTube by 1Furtwangler), delivers a version of extraordinary lyricism, carried by a powerful energy. The line is truly flexible, allowing the conductor to juggle contrasts admirably. The tempi are rather fast, which allows the flame that animates this interpretation to never die out. The frank, sometimes even heart-rending attacks serve a very committed interpretation, much more so than a few years later with the Columbia Symphony Orchestra. A version of great expressive intensity, which reveals a vision made of contrasts with an absolutely fabulous sense of melodic line.

Eduard van Beinum, supported by a fine sound recording (Philips), offers a version of sovereign balance at the head of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra. The timbres are remarkably elegant, the tension organic, this is an interpretation that knows how to reconcile contrasts. Served by rather fast tempi, Beinum gives the orchestral flow a rebound, a constantly renewed pulse. The attacks are clear, the orchestral sections listen to each other and respond to each other, the phrases are all in relief, each note – even the slightest counterpoint – is brought to the fore without the whole being disturbed. Beinum lets the score breathe very well, and never seems to be in a hurry – without dragging it out -, this is a version of ideal balance, a sort of perfection – which sometimes lacks, if one were to reproach it with something, which is not easy, risk, we are not on the edge of the abyss, rather seeing a magnificent landscape without ever having put it in danger.

Eugen Jochum’s version, conducted by the Berlin Philharmonic (DGG), seems to remain the quintessence of the traditional interpretation of the Fourth. The dialogue between the orchestras is as natural as ever, and the symphony is full of nostalgia from start to finish. The thickness of the orchestral fabric – at the same time this is the Berlin Philharmonic – never sinks into any form of heaviness, the attacks are sufficiently marked. The orchestral sound is even, to put it bluntly, quite exhilarating. It is a vision of great balance, perhaps a little less characterised than that of Eduard van Beinum (RCO, Philips), despite some magnificent moments of romanticism. It remains a remarkably homogeneous interpretation, whose topicality remains intact.

Between 1933 and 1974, Leopold Stokowski’s conception did not fundamentally change. However, the quality of the 1974 recording by RCA and the sound of the New Philharmonia Orchestra make it preferable – perhaps also because the first version has not yet benefited from an edition to match. What Stokowski does in the Fourth Symphony is simply monumental! The legato is of staggering formal beauty, far superior to Karajan’s, the energy always renewed, the different moments are differentiated – by tempo in particular – but remain integrated in a formidable unity. The result is an interpretation of remarkable perfection, with original interpretative choices – the acceleration in the coda of the first movement – but fully assumed and in perfect coherence with the whole. Definitely a reference.

Otto Klemperer, at the head of his beloved Philharmonia Orchestra (EMI), gives shape to a thick orchestral fabric. In this enormous sound, with woodwinds that are sometimes a little too stiff, a strength advances and magnificent string phrases allow the melody to express itself – despite some relatively opaque phrases. The slowness does not prevent a certain naturalness, and magnificent attacks – the Pizzicatti of the first movement! – to punctuate a discourse oscillating between power and relative banality. Finally, even if this is a beautiful version, the quintessence of this type of conception will no doubt be found in Giulini’s extraordinary Chicago recording (EMI). As far as Klemperer is concerned, we should prefer a great first symphony and, above all, a magnificent German Requiem.

Fritz Reiner, conducting the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in 1963, delivers a sumptuous recording of true formal perfection. The fact remains that despite its obviousness and naturalness, this interpretation perhaps lacks the expressiveness, sensitivity and above all the calculated unexpectedness that Carlos Kleiber was able to bring to the Fourth Symphony. But despite these few rigidities – Reiner was a real dictator at the desk – we must emphasise this reading of great rigour and exemplary clarity, which for many is still a reference today.

Conducting the Köln Rundfunk Sinfonie-Orchester in 1957, Hans Knappertsbusch ( available on YouTube ) offers a version with a very controlled slowness – even if it sometimes lacks tension. There is a real sense of drama here, and the gravity becomes very theatrical – even if sometimes a little grandiloquent. « Kna » infuses the Fourth Symphony with a metaphysical dimension, while not neglecting the organic character of the score. Even if this type of vision is carried to heights by Furtwangler – who is however much faster – we have here a nice testimony of the metaphysical, dense and violent vision in the Fourth.

Carl Schuricht’s version, with the Vienna Philharmonic, is more of a complaint than anything else. The tension is not very sustained, and despite some beautiful phrases – in the strings more than in the brass – at times it remains rather mannered – which is perhaps accentuated by the sound recording.

Charles Munch offers a version of magnificent clarity. Served by an exceptional recording (RCA Living Stereo), Munch gives an incredible intensity to the fourth. The Boston Symphony Orchestra is full of colour and detail, and yet the melodic line remains taut and central to the discourse. There is a real bounce, and the intensity does not prevent a remarkable balance. Munch’s tempi are very fast, and if this is not a very contemplative or melancholic interpretation, it is not violent either, it is the evocation in the present moment of a past that resurfaces.

Karl Bohm, with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (DG), offers a version permeated by a form of softness. Attempting to offer a calmer vision, Bohm reduces the tension too much, and if a few beautiful moments manage to emerge, the resolution is often too smooth. The dialogue between the orchestra lacks relief and, above all, naturalness, and the key passages are hampered by shrill brass instruments and a lack of balance. However, some good ideas are to be welcomed, and phrases which, if they do not lead to the expected resolution, are in themselves successful.

Evgeny Mravinsky, at the head of his – legendary – Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra, offers a version of hallucinating tension, timelessness, absolutely devastating force and violence. But it would not do Mravinsky justice to reduce him to that, for there is also light – the woodwinds, with, of course, and as with all Mravinsky, the flute – lyricism, and incredible formal beauty. The Fourth Symphony is here the fruit of a vital impulse, seeking to express itself despite all obstacles, which does not prevent sensitivity and nostalgia from being expressed. It is not a flight into the future, it is an interpretation of the moment, almost protoplasmic, that Mravinsky delivers, with an enormous will, desperately anguished but nevertheless alive and courageous. Available from Praga Digitals (coupled with an equally extraordinary Tchaikovsky Fifth), this is one of the most extraordinary testimonies to Mravinsky’s art in Romantic music and, more generally, quite simply one of the greatest recordings of Brahms’ music.

With the NDR Symphony Orchestra, Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt’s version suffers from a catastrophic sound recording (Vox). The crackling, thick orchestral sound can be felt all the same, but it makes the performance a little heavy despite the great energy. The whole lacks vivacity, and the interpretation remains rather frozen.

Rudolf Kempe, in Berlin, already offered an interpretation of the third symphony that was absolutely exhilarating, with a Furtwanglerian violence and intensity. In the Fourth, we find again the « Kempe sound », these marked attacks, this tendency of the brass to surge ahead of the rest of the orchestra, and this differentiation of the sound planes to make the discourse ever more intelligible. However, while there is still a remarkable naturalness here and the tension does not falter, there is none of the wonder of the Third. The very thick sound of the Berlin Philharmonic is perhaps also less suitable for Kempe, who nevertheless draws some very beautiful colours from the orchestra – the woodwinds. The counterpoint and rhythm, though sometimes a little too choppy, are also to be highlighted as a strong point of this performance.

George Szell, with the Cleveland Orchestra, brings relief to the fore. Everything seems to be sculpted with a view to highlighting contrasts and moving forward. The attacks are deep, but there is no lack of sensitivity, quite the contrary. Nevertheless, the line seems somewhat broken, and slowness can be felt here and there. Despite this, a magnificent orchestral sound – the woodwinds! – and superb ideas emerge, making this an excellent performance. That being said, one will find more naturalness on the side of Reiner ( 1963 ). It will therefore be necessary to favour the few live recordings available.

Rafael Kubelik, who conducts the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (Orfeo), delivers an interpretation of a certain lyricism, but which is a little too indulgent in the fullness of sound. The accents are lacking, the attacks are not very sharp, in short it lacks relief and tension. It is therefore a rather smooth Fourth, despite some beautiful moments – only it is not enough to embellish the discourse, which lacks a little truth in all this refinement.

Michael Gielen conducting the SWR Orchestra offers a vision of beautiful drive, with priority given to melodic line and clarity. Even if there is a certain urgency here, this is an interpretation that lacks a little feeling. What made Gielen’s Beethoven, Schubert or Mahler so intelligible is not enough in Brahms’ music. In this kind of vision, we might as well turn to Fritz Reiner’s version.

Hans Rosbaud, with the SWR Orchestra Baden-Baden, delivers a version that is full of evocations, with magnificent timbres, but which nevertheless remains rather smooth. Nevertheless, the line moves forward at a steady tempo and the conducting does not drag. Despite this, one can remain hungry.

Leonard Bernstein, at the head of a Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra in a state of grace (DG), offers an interpretation full of nuance, not without a certain slowness. If drops in tension sometimes lose the discourse, this vision that oscillates between moments of contemplation and moments of beautiful intensity, it is finally with a great relaxation that Bernstein detaches the attacks, especially not playing legato, in what sometimes lacks a little naturalness. However, the VPO gives extraordinary colours to the fourth symphony, and Bernstein emphasises minute details to bring them to the fore, giving them a prominent role and thus bringing them out of their oblivion. This is a very interesting version.

Kurt Sanderling, conducting the Staatskapell Dresden, drags a little. There is, however, a beautiful mastery, which sometimes borders on control – the interpretation would benefit from a little more freedom, it lacks naturalness. The thick orchestral sound also reduces the expressiveness of the discourse somewhat. However, the musical flow remains taut, while what is being expressed seems to change little. In this kind of vision, one should probably prefer Klemperer, or more generally Giulini in Chicago (both available from EMI).

Celibidache’s Fourth, with the MPO (Warner), disappoints. The sound itself is magnificent, the colours splendid, the orchestras respond to each other, it is magnificently executed and yet… it is undoubtedly the conception that poses a problem. For here we have a static Brahms, not only contemplative but above all immersed in the fullness of sound, in the profusion of detail, with a real sense of architecture. Celibidache’s interpretation is very well constructed, with some magnificent moments, but remains irregular and above all makes the line confused, and the listener too. Of course some of the ideas are absolutely brilliant, as always with this conductor, but it simply lacks vitality and freshness – maybe the experience was significantly different in the concert hall. The version with Stuttgart is however more tense, but the formal perfection is less, for a vision that one feels is already in power, and which will be in act in Munich. It is therefore on the Berlin side, in 1945 ( Audite ), that one must listen. This time Celibidache breathes real tension into the Fourth, without denying the beauty of the sound either. The whole is remarkably coherent, and even if there is neither the energy nor the metaphysics of Furtwängler, the only « master » he ever recognised, this version is undoubtedly among the best that our dear Celi could do in Brahms.

Even if Giulini’s Viennese version (DG) lacks tension and is relatively heavy, the much more contemplative version recorded in Chicago (EMI) is to be commended. The sound is paradoxically much more beautiful, the timpani less marked, the chords marked despite a magnificent legato, and the fourth is here full of life, each bar seeming to take on more flesh, in a vision of true sensuality. Where the Viennese version may seem a little static, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra rises to a bewildering formal perfection, an embodiment of the Beautiful even in a sense – at least in the discography of the Fourth Symphony – as the tension is magnified, the power quite enormous, in key passages and transitions. Giulini remains, in this respect, a master in the interpretation of Brahms’ symphonies.

THE MODERNS

How can we talk about the Fourth Symphony without Carlos Kleiber? With Tuscaninian drive and expressiveness, metaphysical power and Furtwanglerian strength, Kleiber reconciles the concerts in a demiurgic interpretation, bringing out the best in the colours of each orchestra he works with. In 1979 (Memories) and 1980 (DGG) with the Vienna Philharmonic, the score was never so silky, with a legato that links up wonderfully with very fast tempi – the fourth movement! -The result is a unique formal perfection. In 1994 in Berlin (Memories), it is violence that prevails, where Vienna was Apollonian, it is now Dionysian – but we must take into account the sound recording, which is precarious to say the least, let us pray that it has been recorded by the radio and that it will be officially released one day. Where in 1996 in Ingolstadt (Memories) we witnessed an extension of the Berlin interpretation, the live filmed performance with the Bavarian State Orchestra seems lighter, perhaps less dense, less tense, but with the arrival in Kleiber’s vision of a contemplative aspect, more depressive in a way, in any case more nostalgic, full of regrets. Finally, the admirable reconciliation between all these visions, which are so similar on the whole and yet so different in detail, is to be found in the last available concert of Kleiber conducting Brahms, that in Lubjana in 1997. If one were to recommend only one performance of the Fourth, I think Kleiber would be a good candidate, the version remains to be determined – perhaps the 1979 live recording, to begin with anyway, but that’s just my opinion.

Bernard Haitink’s version, conducted by the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (Philips), is a perfect example of what can make an Apollonian vision of the Fourth Symphony successful. Carried by a sublime sound recording, Haitink brings the instruments into dialogue in a balance that allows the score to express itself, all in restraint, but knowing how to keep the intensity in the transitions and the exposition of the themes. The Concertgebouw’s timbres are full of colour, and the ‘melancholy of powerlessness’ – in Nietzsche’s words – seems to be immanent in the music itself, without any artifice. This is a benchmark in its genre.

Riccardo Muti, conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra (Philips), seeks to paint a landscape of nuance. The problem is that the contrasts are completely smoothed out, and despite the elegance of the Italian conductor’s direction there seems to be only a nostalgic description, and not much more.

Georg Solti, at the head of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, delivers an interpretation carried by a beautiful energy. In a vision that is admittedly sometimes a little monolithic, Solti always leaves the melodic line in the foreground, even if it means overlooking certain details, but giving the Fourth Symphony a theatrical dimension. The brass of the Chicago Symphony is very bright – a little too much so perhaps – and the strings are above all there to support the discourse, which is always very tense. But here we have a very narrative version, an example of what Solti can achieve in the symphonic repertoire.

Gunter Wand, with the NDR Sinfonieorchester (on Profil) offers an Apollonian vision, contemplative without ever losing the melodic line, despite some drops in tension at times – the last movement. But there is here a sense of detail, a highlighting, a way of making the text absolutely intelligible. The NDRSO’s sound is round without altering the attacks, the strings are deep, the woodwinds have a thousand colours and the brass are often in the foreground without ever becoming demonstrative. Finally, unlike Haitink, who has already fallen into pure nostalgia, Wand seems never to resign himself, and gives an interpretation full of hope, and of a striking beauty.

Claudio Abbado, with the Vienna Philharmonic, in 1992 (on DG), delivers a refined version of remarkable balance. However, the magnificent colours and the extraordinarily elegant dialogue between the orchestras – the way the musicians listen to each other is just amazing, as usual with Abbado – place the relief in the background – some moments are even frankly smooth. There is, however, a mastery, whether of exposition or transition, which illuminates the whole symphony with an absolutely splendid brilliance. Perhaps Abbado could be criticised for lacking in contrast, but it is nevertheless a perfectly executed performance.

Charles Mackerras conducts a smaller ensemble. His Scottish Chamber Orchestra sounds as usual marvellous, and the conductor’s playing is extremely natural. Of course, a chamber orchestra playing a Brahms symphony upsets our listening habits. Much more brass – which regularly overpowers the rest of the orchestra -, drier timpani, a thinner string sound – but silky all the same – and woodwinds brought back to the forefront of the discourse, these are the elements of a remarkably elegant version.

Riccardo Chailly, conducting the Gewandhausorchester, rushes through it all. Obviously, the narrative is in the foreground, but it seems rather forced. This is not an architecture that is built up step by step, it is a kind of frantic race without feeling, full of virtuosity certainly, but where the listener is left out from the start – and in fact, what was intended to be tense remains hermetic. With the same orchestra, if you have to choose a recent version, you might as well go and listen to the almost exact opposite version recorded by Herbert Blomstedt.

Simon Rattle and his Berliner Philharmoniker deliver an interpretation teeming with detail, based more on the colours and the sound itself than on the melodic line – and unfortunately this sometimes takes precedence over the clarity and intelligibility of the discourse. But despite everything, what elegance and refinement! Moreover, the tension remains present, though sometimes slightly fluctuating. Finally, this remains a good version, very balanced overall, despite a certain complacency in the fullness of sound.

Robin Ticciati, with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, plays with a small ensemble – and, it seems, on period instruments. Without vibrato, the sound planes are very well layered, but the phrases sometimes suffer from mannerisms, when a certain brutality intrudes here and there. The fact remains that this interpretation is full of superb moments – the Andante moderato! -. The lightness is still very welcome, and we have here a version that brings a breath of fresh air and even renewal to the discography. I look forward to seeing what the next few years hold in store for historically informed Brahmsian interpretations.

Herbert Blomstedt is perhaps the finest ambassador of the Brahms symphonies today. In 2021, in a splendid recording (Pentatone), Blomstedt takes the sound of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra to absolutely heavenly heights. The strings seem to be made of silk, the woodwinds marking the rhythm without denying either the pain or the regret, the brass is of an astonishing verticality, and despite the slowness it is indeed an interpretation of extraordinary depth that advances. Everything evokes pain and nostalgia, sometimes enormous, but without violence, for it is interiority that prevails here. The second movement is an example of contemplation, the last one seems like a Farewell, and it is without any excess that this version sketches out a new ideal.

Laisser un commentaire