Wilhelm Backhaus is often described as the embodiment of the traditional pianist, sometimes a little austere, a little cold, and in any case it is neither joy nor virtuosity that comes first to those who speak of him. Yet Backhaus’ playing appears to be much more complex than it is often reduced to.

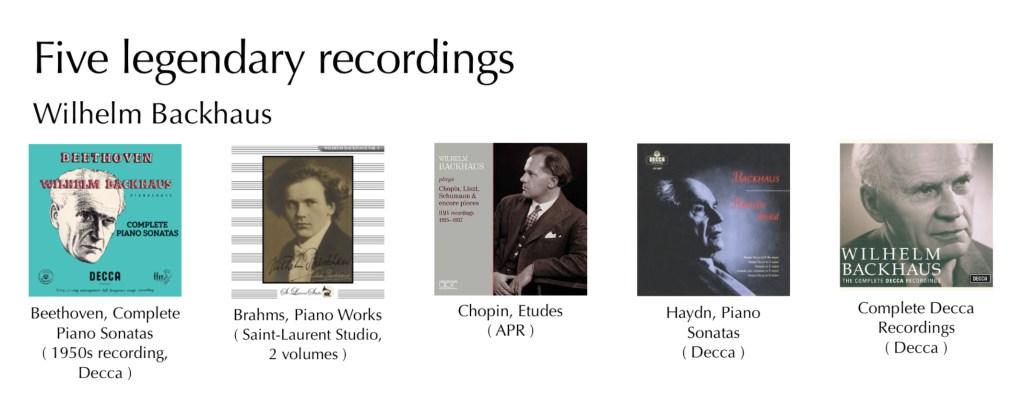

Wilhelm Backhaus was born in Leipzig in 1884. A student of Eugene d’Albert, he met Brahms at the age of eleven. He won the Anton Rubinstein Prize in 1905, ahead of a certain Béla Bartók, and had a long career until his death in 1969 at the age of 85. Backhaus was an acknowledged interpreter of the traditional German repertoire, including Bach, Beethoven and Brahms, and notably two complete Beethoven piano sonatas, the first of which, recorded in the mid-1950s, remains a near-absolute reference to this day.

Backhaus has often been referred to as a cold pianist, as ice or marble. In reality, Backhaus can simply sound quite analytical at times in the studio. When one listens to Backhaus on recordings from the 1920s or 1930s, what immediately strikes one is his immense and very impressive virtuosity, which allows the performer great expressiveness. Thus the pianist can afford never to make an effect, never to add more, since this virtuosity adds the magic, as if metaphysical, necessary to make the composition stand out. This extraordinary virtuosity typical of Backhaus’s early recordings is particularly well embodied in Chopin’s Etudes ( recorded in 1927 ), which oscillates between tragedy and romantic excitement while retaining its necessary degree of control, with the right amount of freedom and precision.

Backhaus’s playing had an extraordinary breadth that gave substance to his sound and gave his interpretations immense power. Through the recordings we can notice what sounds like a musical flood that seems to overwhelm everything. This combination of breadth and power allows Backhaus to nuance as if by the climaxes: it is as if the nuance had to be set for the climaxes, whereas with most pianists it seems that one has to start from the climax and work around it – as with Sofronitsky, for example.

I suggest that you listen to Backhaus playing the first movement of the Hammerklavier, with that absolutely enormous breadth that combines a continuous musical flow with a lot of nuance, and a delicacy that one often thinks of less when one mentions the name of Wilhelm Backhaus.

When one listens to Wilhelm Backhaus’s interpretations, what is perhaps most apparent is the energy that emerges, which acts as a regulator and brings the piece to life. These are also flows of energy that articulate the different moments of the composition to make them coherent, to make them intelligible. Backhaus’s interpretations are initially earthy in this respect, but the pianist pushes to the extreme all the material that he shapes to construct his interpretation. The composition is thus revealed as a whole, not as a series of moments that follow one another and are, in fact, more or less irregular. One finds this spirituality that one does not always think of when speaking of Backhaus in his interpretation of the adagio of Haydn’s sonata in E flat major, which is both very luminous and full of an energy that gives this composition a dimension that it never usually attains.

Whatever the period, Backhaus’s style is characterised by an uncommon ability to shear interpretation into the piece itself, like carving the composition out of rock – not ice – to achieve what appears to be an absolute truth. This ability to reveal the truth is in fact

to be qualified, at least on the following point: it is a clear and rather dark truth, sometimes even rather pessimistic. Yet everything is far from black in Backhaus, and the pianist knows how to adapt to the work he is playing, and if certain works require at least some clarity, Backhaus also knows how to bring light to them. But light is also something that the pianist nuances, playing with the contrasts in Schumann’s Fantasy, for example, to bring out something generally clear, which at first sight moves forward in a relatively classical manner.

However, at the turn of a bar or a detail, the pianist knows how to surprise us. It is not the colours that are immediately striking when one listens to Wilhelm Backhaus, but this icy atmosphere, which is above all filled with a great deal of light. In this respect, Backhaus’s interpretations seem to be like paths, galleries cut into the rock, in rather dark mountains. In this sense, Backhaus cultivates contrasts and seeks, in a genuine search for subjectivity, to amplify the full force of the piece, and the performance thus becomes extremely narrative.

One of the proofs of all the expressiveness that could emerge from the narrative, from the climate that Backhaus was able to create, is the recording of the last two Beethoven concertos with Clemens Krauss, whose slightly conducting and lively style marries marvellously with the pianist’s precise playing. I suggest you listen to the second movement of the fourth concerto.

Wilhelm Backhaus was a complete and extremely modern pianist with a much broader repertoire than the public often reduces him to today. He was perhaps the only one to reconcile all the monumentality of the great repertoire with the finest precision and a certain delicacy, which can be heard particularly in the contrasts that structured his concerts – and I can only recommend that you listen to every concert you can find by him. On the other hand, if you want to listen to the complete Beethoven sonatas, I think the Backhaus discs from the 1950s – the mono version is better than the stereo – are an excellent choice, for me the best along with Claudio Arrau and Yves Nat in the regularity and consistency of all these different works.

Sources : Alain Lompech’s book « The great pianists of the 20th century » and Wikipedia – for biographical clues.

Laisser un commentaire